‘Minari’ Will Leave You Crying Over a Bunch of Produce

The untold story of first-generation Korean Americans in the rural South

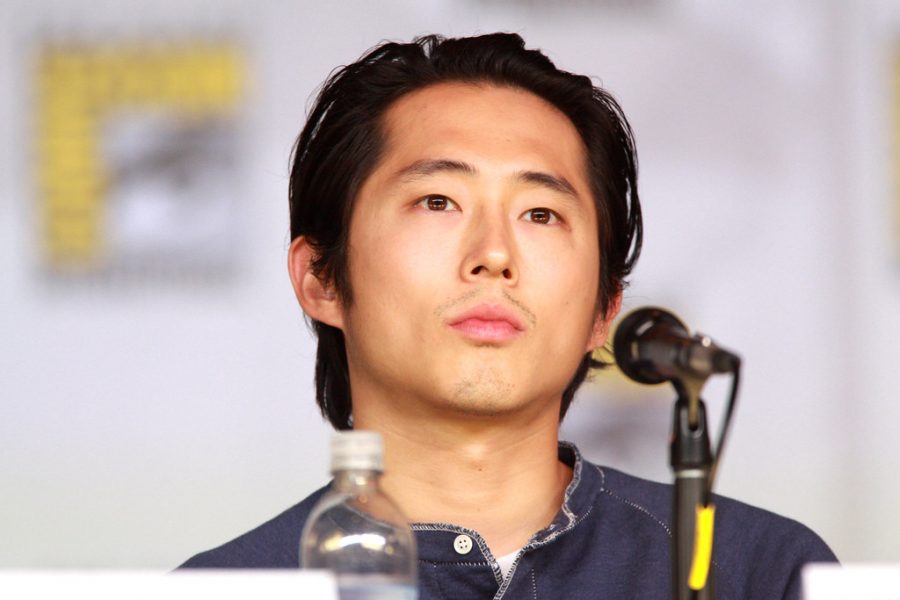

GAGE SKIDMORE VIA FLICKR

Steven Yuen, who plays Jacob, speaks to the press. Jacob is the father who decides to move his family from California to Arkansas and start growing Korean produce.

March 7, 2021

Written and directed by Lee Isaac Chung, “Minari” is a story of a 1980s Korean American family who move to Arkansas in pursuit of the American Dream. A Sundance Grand Jury Prize winner, the film is a meditation on the experiences of an immigrant family trying to make sense of their life in the larger context of Reagan’s America.

Jacob Yi (Steven Yeun), the father of the family, buys a plot of land in Arkansas with dreams of, first, escaping the oppressive landscape of 9-to-5 working-class California and, next, growing Korean produce with the purpose of selling it to other Korean immigrants. Not everyone in the family is excited at the prospect of living a rural life. Monica (Han Ye-ri), Jacob’s wife, misses the Korean community they left behind and fears for her son David (Alan Kim), who has heart problems. David himself seems to be excited at the prospect of living in the countryside and farming with his dad, but his perception of life is challenged by the arrival of his grandmother, Soon-ja (Youn Yuh-jung).

The film’s exploration of its themes is as refined and understated as its cinematography. As the only Koreans in the area, you would expect the Yis to fall victim to the casual racism of their white southern neighbors; however, what the family experiences is more nuanced than explicit bigotry.

“Minari” proves that immigrant stories don’t need to end in utter devastation and can end on an uplifting note.

At church, one of the only points of interaction with the outside world we see in the film, Monica feels isolated not because of other women’s attitudes toward her (they actually compliment her), but because of her poor knowledge of English. The children themselves — David has an older sister, Anne (Noel Kate Cho) — are torn between assimilation into American culture and the pressures their parents bestow on them to maintain their Korean identity.

In fact, Paul, Jacob’s white farm helper, experiences more overt discrimination because his behavior doesn’t fit with societal norms (possibly caused by PTSD, neurodivergency or both). The subtlety and variety of the bigotry present in the film reminds us that discrimination and prejudice comes in forms less explicit than overt intolerance.

Another refreshing thing about “Minari” is that it’s not burdened with a life-or-death conflict; rather, Chung chooses to focus on a personal struggle to make meaning out of life in a foreign country, an experience that is integral to the lives of many first-generation immigrants. The film’s name itself derives from an especially resilient edible plant that grows in Korea. Like minari the plant, the characters of “Minari” are resilient; they continue with life despite, and sometimes in spite, of their failures and setbacks.

We feel for the characters, however, not because of the grandeur of the problems the film throws at them (although some of them are definitely not small inconveniences), but because of how personally attached we become to the characters through understanding their inner aspirations.

The character that ties everything together is Soon-ja. Unlike the rest of her family, she, an elderly Korean woman, does not experience the desire to find a (both literal and metaphorical) place within the American landscape. She is repeatedly perceived as “ungrandmalike” by David: She plays cards, swears and watches wrestling matches on TV. She also can’t cook.

However, it is Soon-ja who plants the minari seeds, Soon-ja who makes David believe in his strength despite his heart (and confidence) issues, Soon-ja who comforts and steadies her daughter, and Soon-ja who gives the family her personal savings when it runs into trouble. As the “strongest” character in the film, we expect her to fall into peril the least — which makes it all the more devastating to viewers when she does.

“Is this capitalist propaganda, if the film ends with Jacob still persevering at his dream, not disillusioned?” you may ask. I would say no. Jacob fails over and over again. The high prices of water cause the family to go without it in their house just to ensure the farm’s survival. The farm cannot provide a full escape from the capitalist economy the characters have to live in; however, to Jacob and Monica, it’s an improvement from an oppressive working-class job, sexing recently hatched chicken, for which Monica was not fast enough in California. If this is not a commentary on the economic practices of the 1980s, then I don’t know what is.

“Minari” proves that immigrant stories don’t need to end in utter devastation and can end on an uplifting note. It challenges the “trauma porn” trope American media often falls into when depicting the experiences of immigrant families. “Minari” does not shy away from portraying its characters at their weakest — it also portrays them at their strongest.

“Minari” does offer a broader commentary on racial dynamics, belonging and alienation. However, to focus too much on it, in this case, is to divert attention from the particular experiences of the Yi family. A semi-autobiographical work, “Minari” is a subtle yet deeply personal tale of an immigrant family and should be watched as such. Chung’s mastery in “Minari” will no doubt be noticed by the Academy in this year’s nominations.