A Tale of Two Stressors: Online News and COVID-19

October 28, 2020

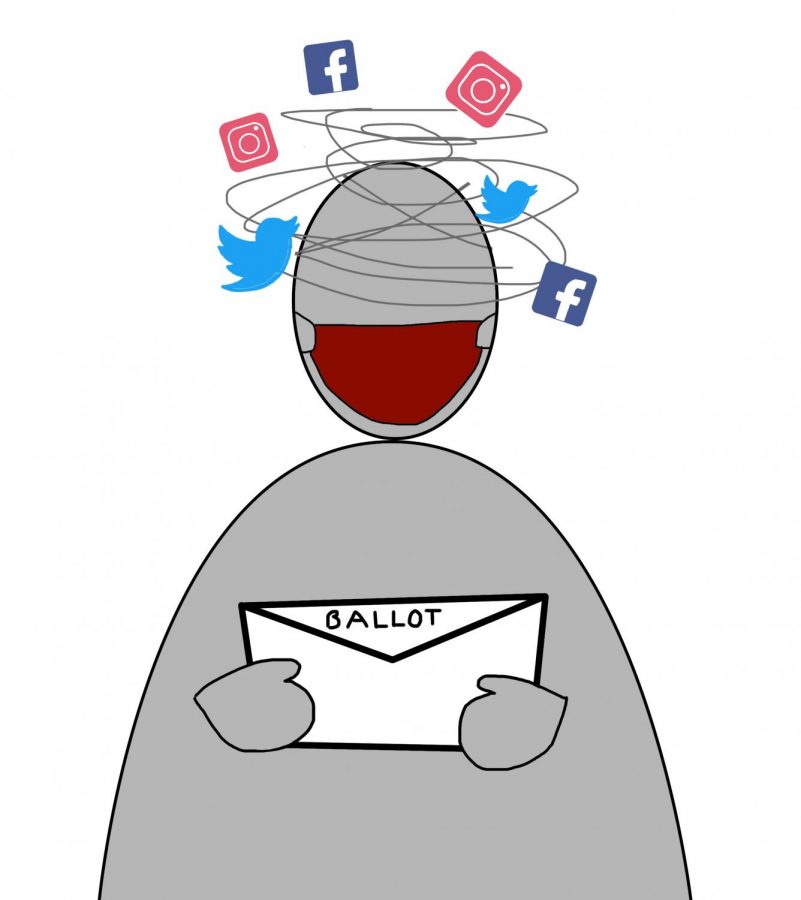

In this age of social media, we can get instant information from around the world delivered into the palms of our hands. However, with this unprecedented access comes negative consequences for our own mental health, especially during the U.S. presidential election and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, both of which have made news cycles especially saturated and overwhelming.

Anxiety itself is a complex and multi-dimensional mental state that manifests in a variety of ways. According to Professor Dean McKay of Fordham’s psychology department, anxiety at its root is “an action tendency where someone is prepared to respond to some kind of perceived or real threat in order to confirm safety.”

Anxiety is a natural behavior that is ingrained within our psyches. McKay described three categories of threats which can trigger anxiety: real threats, or actual physical dangers; false alarms, or ambiguous stimuli like a shadow in your room at night; and learned alarms, or specific stimuli such as phobias of certain animals or situations, according to McKay.

While anxiety is a natural response and entirely normal to experience, too much anxiety or the persistence of anxiety-inducing situations can worsen one’s anxiety or even develop into an anxiety disorder.

Social media, the predominant medium that Americans use to consume news and interact with others, has been linked to increased anxiety in users long before COVID-19 or the 2020 election dominated the country’s discourse.

“You repeatedly get information about that, but it doesn’t leave a conclusion that you’re going to be safe — that’s going to foster anxiety.” Professor Dean McKay

McKay explained that social media outlets “are specifically designed to keep users coming back for more.” Social media apps keep users engaged and active on their platforms by tailoring content to peoples’ interests and anxieties based on the content they most frequently consume and interact with.

People who are already prone to anxiety are particularly vulnerable to this model, McKay explained. Those who frequently read the news may be estimating the perceived threat to be more dangerous compared to those who don’t check the news as often.

Combined with the methods used by social media companies to keep users engaged on their platforms, an already-anxious person will further overestimate the threats they read about when using social media.

”Under these circumstances,” McKay said, “you repeatedly get information about that, but it doesn’t leave a conclusion that you’re going to be safe — that’s going to foster anxiety.”

Phone notifications may be especially unhealthy by forcing users to check their phone. People whose phones give off notifications more frequently were found to also report higher instances of stress, anxiety and depression.

Political and pandemic anxiety may be different in nature and cause, but the perceived and real threats that both entail can result in anxiety and stress, especially in those who are concerned with their well-being.

The pandemic “has had consequences for mental health across every dimension,” said McKay, citing in particular the increase of reported anxiety among the public as well as an uptick in diagnosed anxiety disorders, which he attributes to the varying degrees of stress that the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns have had on people.

While social media can be effective in spreading information to prevent COVID-19, it has also allowed misinformation and conspiracy theories about the coronavirus’s origins and treatment to spread at unprecedented speeds. This “infodemic” of disinformation threatens not only health professionals and workers who are actively fighting to combat COVID-19, but also the people who consume and fall for misinformation. In light of this, people who frequent social media should be wary of alarming or eye-catching news, especially if the content gives extraordinary claims like a “miracle cure” or has some sort of promotion involved.

Anxiety related to COVID-19 is rooted more in our instinctive tendency to avoid infection and contamination, a phenomenon McKay called the “behavioral immune system.” In instances where humans are aware of a pathogen, they may be predisposed to keep themselves clean by practicing self-cleaning behaviors and being more apprehensive of any real and perceived threats of infection.

“One of the reasons why you see news stories that show young, healthy people dying from COVID, besides the tragedy, is to highlight the fact that more people are vulnerable to it.” Professor Dean McKay

External influences such as government mandates encouraging social distancing and mask-wearing are no doubt very important in curbing the spread of a pathogen such as COVID-19, although McKay added, “We’re kind of hardwired to start doing that already, to some measure.”

However, the pandemic induces additional stressors, including economic ones like job security and financial stability, as well as health-related ones like fear of infection and the real threat of catching COVID-19. These can be particularly triggering to vulnerable individuals, leading them to more uncertainty and thus more anxiety.

While the behavioral immune system has been documented as a legitimate mechanism, plenty of people are hesitant of, and even actively defiant towards, the real and perceived risks of COVID-19. According to McKay, this is due to the “perceived vulnerability of disease,” or how vulnerable an individual feels they are to a disease and being infected. The degree of vulnerability can be further reduced in people who don’t feel much or any economic stress or personal dangers of COVID-19, such as knowing individuals who have been severely infected with COVID-19 or who are suffering financially.

But while apprehension of a reported danger is natural, the politicization of COVID-19 and sharing of misinformation can severely disrupt healthcare workers’ efforts at containment. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a particular topic of misinformation and hearsay, notably from President Donald Trump, who himself was infected with the coronavirus in early October. Spreading misinformation from a position of power is especially dangerous as it not only means that the government may be relying on faulty or non-factual information, but also undermine public trust and confidence in the government and its proposed containment measures.

McKay demonstrated how the media helps spread awareness of COVID-19 by reporting on cases of young healthy people dying of the coronavirus, explaining, “One of the reasons why you see news stories that show young, healthy people dying from COVID, besides the tragedy, is to highlight the fact that more people are vulnerable to it.”

If anxiety continues to preoccupy your life, and especially you start missing work or avoiding interpersonal relationships because of it, it may be time to start speaking with a mental health specialist. Jeffrey Ng, director of Counseling and Psychological Services (CPS) at Fordham, encouraged students to schedule a virtual session with a licensed counselor. CPS also offers several self-help guides for coping with stress and anxiety brought on by COVID-19.

Fordham CPS will additionally be offering scheduled support spaces for students to discuss socio political and election-based anxiety. Students can virtually attend any or all of the two pre-election discussions, scheduled on Friday, Oct. 30 and Monday, November 2, as well as three post-election sessions, one each occurring on November 4, 5 and 6, respectively.