The Choice to Vote Polarizes Student Body

Pressure from voters and pushback from nonvoters has created a new discussion around elections

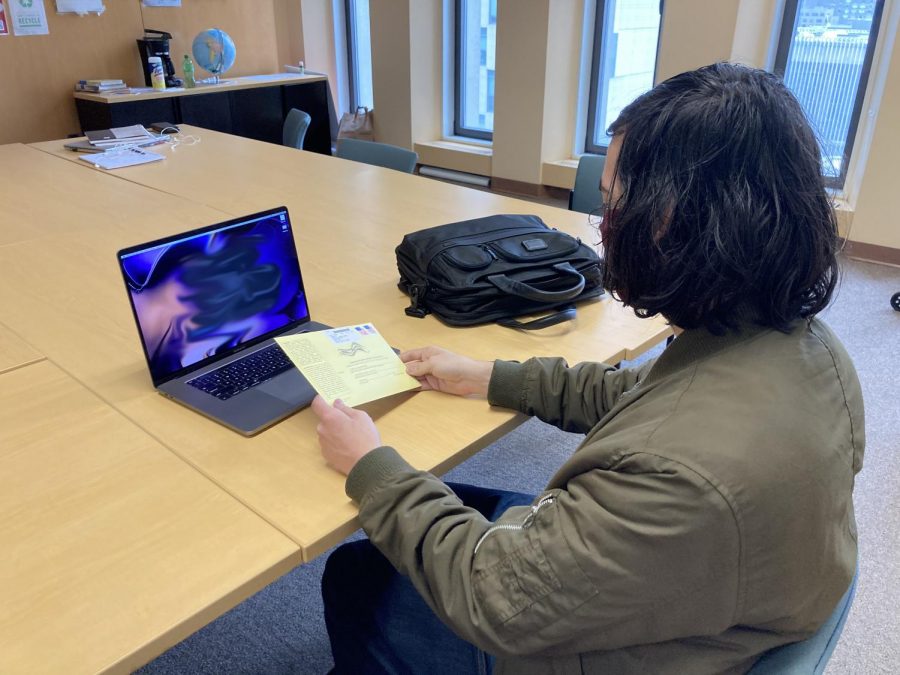

A student signs and seals their absentee ballot. In the upcoming election, the decision of whether or not to vote has been influenced by concerns with mail-in voting and disagreements with each candidate’s platform.

October 26, 2020

When it comes to the act of voting, the Fordham Lincoln Center campus community is not unified. In the 2020 United Student Government (USG) presidential election, the voter turnout rate was only 13%. Now, the student body is still divided as students are tasked with voting during a pandemic for the upcoming national presidential election.

An anonymous political survey of 211 Fordham students conducted by The Observer found that 93.4% of students planned on voting in the upcoming presidential election. A short response question prompting students on their opinions of their peers who choose not to vote produced polarizing results, with the majority of the results condemning the practice of abstaining from voting.

“I take massive issue with those that are able to exercise their right to vote and still opt not to with no good reason,” one respondent wrote.

“They have an underdeveloped moral compass and little to no sense of purpose,” another student said.

“There’s this sense of a lack of compassion for others if you do not exercise this right.” Katrina Shea, FCLC ’22

Other students answered in defense of those who did not vote, creating a stark contrast of beliefs.

“It is people’s right to resist the illegitimate political system of this country,” one student stated.

“I completely understand if there are BIPOC students who do not feel like it is even worth it to engage in an election that they know, regardless of outcome, will harm them,” another respondent said.

Contrary to the wide array of sentiments about voting, 63.5% of respondents said they believe that the Fordham community shares the same political beliefs as them.

Cases Made Across the Spectrum

Katrina Shea, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’22, advocated for voting, emphasizing the need for everyone to practice their civil liberties.

“I think that it’s extremely ignorant to deny the fact that voting does have some sort of impact on what our daily lives look like,” Shea said. “There’s this sense of a lack of compassion for others if you do not exercise this right.”

Shea is voting for Joe Biden as president, even though she is very doubtful that the issues she cares about will be addressed if he is elected. “It will certainly be a lot better than what we have right now,” she said.

Shea also thinks the two-party system is flawed because voters are required to choose “the lesser of two evils” instead of other candidates they could support. However, for the 2020 election, she called voting for a third-party candidate ignorant because the chance of them winning is unlikely.

“I don’t think it’s a bad thing to do. I just think people think it’s the only thing you can do.” Cam Dasher, FCLC ’22

According to The Observer’s survey, 87.7% of students are not in favor of two-party control in the U.S. government.

“I understand why people do not vote because some people do not feel safer or more comfortable with either party,” Em Krichmar, FCLC ’21, said. “I particularly understand when BIPOC or low income individuals abstain from voting because neither party has proven themselves to be truly allied with these communities.”

Krichmar does not identify with any American political party — along with 17.1% of the survey’s other respondents — but voted for Biden due to his potential to be “safer and at the very least less violent” than Donald Trump.

Cam Dasher, FCLC ’22, was more skeptical of the effectiveness of voting than Shea and Krichmar. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with voting,” Dasher said. “I don’t think it’s a bad thing to do. I just think people think it’s the only thing you can do.”

73.9% of student respondents said they do not trust the U.S. government to serve justice or do what is morally right. Yet, Dasher has experienced backlash for critiquing the electoral system and politicians, even though they still plan on voting because they have the privilege to do so.

“If you’re not critiquing candidates and you’re just letting these people exist in a vacuum, then nothing’s going to change.”

Woody Wisz, FCLC ’23, chose not to vote for president. However, they did participate in certain state and local races, such as North Carolina’s elections for the commissioner of labor and health and the human services director.

“I don’t fundamentally believe that either Joe Biden or Donald Trump will significantly decrease the power of state security in the US, or would refuse to engage in imperialism in neocolonialism elsewhere. I think they’re both imperialists and I know that they’re both documented rapists.”

Wisz said they are voting selectively in races that they think will alter the material conditions of people in their community.

“It’s awkward being at odds with such a unanimous message, but it’s not out of indifference. It’s my choice.” Bruno Palomares, FCLC ’23

Bruno Palomares, FCLC ’23, is also a nonvoter. “It’s awkward being at odds with such a unanimous message, but it’s not out of indifference. It’s my choice,” Palomares said he feels pressure from his student peers to vote — especially over social media, where timelines are spammed with voting posts.

He called his choice “more cynical,” but the “most principled” since he said he believes that nothing will undergo meaningful change after the election, regardless of who wins.

Both candidates toe “the corporatist status quo of their respective parties — increasingly an ultimately meaningless distinction — all while lying to our faces about their well meaning intentions,” Palomares said. “So then why must I choose? Why ought I participate in a political system that bestows power without accountability?”

How Voter Suppression Impacts Students

According to The Observer’s survey, 38.4% of students feel like their vote has been suppressed.

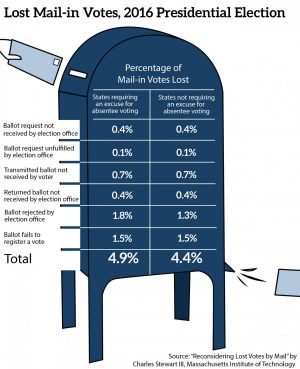

Dasher, like many students, is not confident about their vote being counted due to state restrictions and the dismantling of the United States Postal Service. Their home state of Texas, among 20 other states, has barriers that make absentee voting even more difficult — including the requirement of an excuse to receive a ballot.

“It’s not good for students right now; I just feel like we’re getting sidelined. They’re defunding everything that we need to actually engage with electoral politics,” Dasher said.

“The restriction of information is a suppression tactic, even if it doesn’t look like armed guards at polling stations, or the removal of polling stations.” Woody Wisz, FCLC ’23

More than five million Americans are unable to vote in the 2020 election due to various forms of voter suppression — including felon disenfranchisement, voter ID laws, registration restrictions and gerrymandering.

Dasher is from Houston, where they said that gerrymandering in Harris County is “really really bad.”

“All of the lower income neighborhoods are all grouped together into one district, but for some reason, there are a lot of smaller districts that are all upper white class.” According to Dasher, there is only one location in Harris County that accepts absentee ballot drop-offs: “that’s suppression in and of itself.”

A survey conducted by Pew Research Center in 2018 shows that nonvoters are disproportionately composed of young, poor and nonwhite citizens.

Wisz cited examples of voter suppression in their home state of North Carolina, in districts where the state’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are established.

“The restriction of information is a suppression tactic, even if it doesn’t look like armed guards at polling stations, or the removal of polling stations.”

Stigma Around Voting

Less than half of citizens from the age of 18 to 29 voted in the 2016 presidential election, reinforcing the stigma that young people do not vote.

Shea said she believes a shift in youth electoral participation is happening due to the increase in online activism through social media.

“I’m very excited to see what the younger generation’s turnout is going to be this election because I definitely think that it will be stronger than has been in the past,” Shea said.

It is unclear yet how young people’s recent high levels of civic engagement will translate to voter turnout.

Prior to the 2016 election, the number of youth-led demonstrations rose, but the election produced a 5% decrease in youth voter turnout from the previous 2008 election due to a prioritization of activism over voting.

“I think if you’re exercising your right to vote and you have that privilege, and you’re not doing any other work outside of that, there’s no point in voting in the first place,” Dasher said.

Many students who defended the choice to not vote pointed to other methods of creating change in the U.S. that did not involve casting a ballot.

Wisz said that they organize a food distribution program every weekend that gives food directly to housesless people in one of Raleigh’s city parks.

“I think that something like that has a much greater impact in the lives of people day-to-day than any vote,” they said. “So I may feel pressure to vote, but I’m not really concerned by it. Because the people telling me about it aren’t out there on the weekends with me.”

As November approaches, students who are seeking change through direct action and those who seek change through voting advocacy will have the opportunity to join forces and coordinate efforts against post-election injustices.