Mail-In Voting Isn’t the Solution You Hope It Is

September 2, 2020

In the era of the coronavirus pandemic — a clause that begins every article these days — one of many things weighing heavily on Americans’ minds is the upcoming election in November. Many states have turned to mail-in voting, whether that’s mailing all eligible voters their ballots, having them request ballots or allowing them to use an illness excuse relating to the coronavirus.

As great as this sounds — not having to go to your polling place, not having to take the day off work, not having to see other people — mail-in voting isn’t the solution you hope it to be. There are far too many problems for it to work efficiently and effectively, and voting by mail invites a higher risk of voter disenfranchisement than it purports to prevent.

First, let’s look at mail-in voting’s very recent past: the primaries. In California, 100,000 mail-in ballots were “rejected because of mistakes.” In New York, absentee voters did not receive their ballots until after the election. As far back as July 16, the Washington Post reported that absentee ballots in Wisconsin, Ohio and Texas, among others, were lost or not received by the postal service.

We all know that government service is slow — haven’t you been stuck waiting at the DMV to renew a license? The postal service is the same way; they need you to send in your ballot by Oct. 20 (two weeks before the election) in order to process it in time, but even that does not guarantee that your vote will be counted: The ballot could be lost, marked up or damaged.

Voting by mail invites a higher risk of voter disenfranchisement than it purports to prevent.

If the state is mailing ballots to voters, there’s also no guarantee of them reaching voters in time for the election. Even if you have lofty plans to return your ballot long before the deadline, the state (and postal service) may not support that goal. It could be stolen (by mistake or on purpose, for any party affiliation); it could be tossed as if it were junk mail; anything could happen to it, because even first-class mail is not all that secure or reliable.

I don’t want to get into the postal service debate, but it hasn’t been efficient for years, ever since the amount of mail sent has decreased starting in 2006.

Let’s say that, best case scenario, you send in your ballot on time, it’s received by the election office early, and you think everything is hunky-dory. You have no way of knowing that your vote has been invalidated for any number of reasons, and little do you know that your vote can’t be counted. Maybe it’s sitting in a forgotten bin. But more likely, maybe there’s a stray mark on the ballot — from your pen, your younger sibling, the postal system — and the entire ballot is invalid.

Perhaps when voting for county councilmembers, you checked off two or four of the requisite three candidates. If you were voting in-person, the machine would register a missing or extra mark and have you fill it out again, but if you mail your ballot, you don’t have that luxury. Your vote for president may be invalid because you accidentally voted for an extra person for County Council. Sure, people can make sure to read all the instructions and do it as carefully as possible. Hasn’t that been the goal for voting no matter what the year? But mistakes still happen.

As much as we’d hate to admit it, mail-in voting is very risky. The number of ballots invalidated or lost today is greater than the difference in votes separating the candidates in both the 2000 and 2016 elections — in a close race, these ballots could change an election’s outcome. The idea that the same could occur in the upcoming election makes it even more contentious than it currently is. By voting early or in-person, you minimize the risk of your vote being lost, silenced or deleted. Your voice matters, and any virus or any government worker should not have the power to silence you.

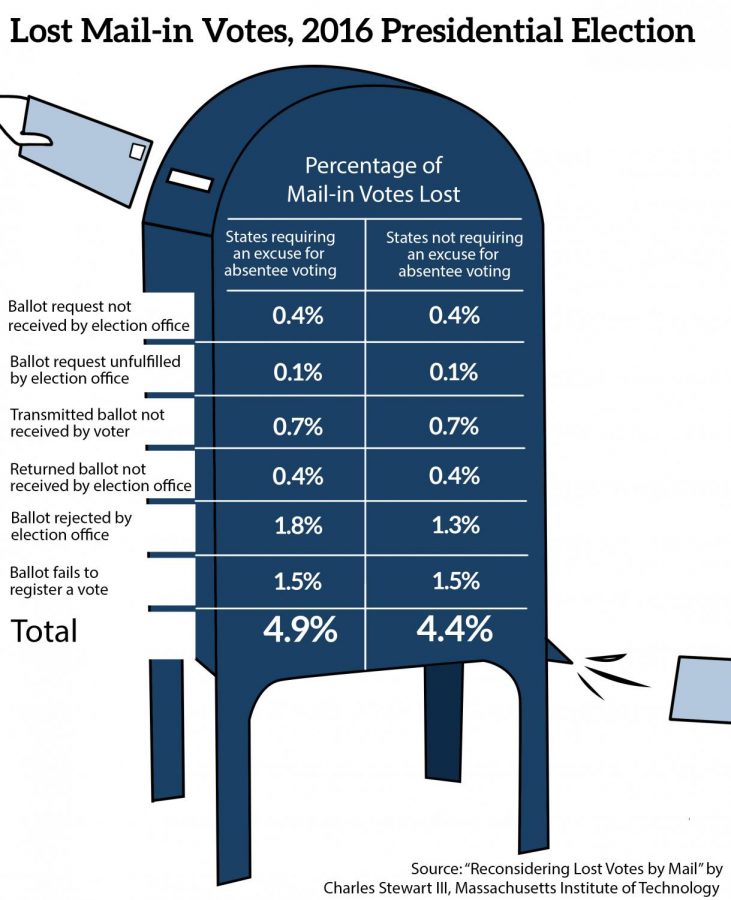

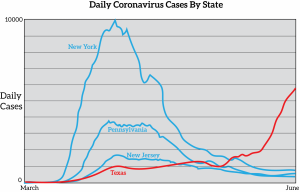

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in an interview with National Geographic that voting in-person would be safe with the precautions we currently have in grocery stores and other public places. If you are comfortable in a grocery store (or, as New Yorkers, on the subway), you should be able to feel comfortable waiting around in a school cafeteria to vote. According to the Harvard Data Science Review, the increased risk of having your ballot not counted via mail-in voting ranges from 3.5 to 4.9% depending on the state. New York’s positivity rate for the coronavirus is at 0.69%, my home state Maryland’s rate is 3.26% — in these and many other states, you are more likely to have your vote invalidated than catching the virus while voting in-person.

By voting early or in-person, you minimize the risk of your vote being lost, silenced or deleted. Your voice matters, and any virus or any government worker should not have the power to silence you.

Mail-in voting may seem like a solution for all, but it should only be used by some — for example, people who live out-of-state, who live abroad, or who are otherwise unable to go out and vote for severe health reasons. That’s called absentee voting, not mail-in voting, and there’s a lot fewer people who partake in it, so the numbers are more manageable. But my parents and neighbors have no true reason to vote by mail if our polling place is less than a mile away and the room is large enough to social distance. Voting by mail is not worth the risk of unwilling disenfranchisement due to errors from the voter, the postal service or the election office.