Back to School (Shootings)

With the return to in-person learning, students are once again navigating busy halls, after-school activities and the threat of active shooters

After a year of being in school online, students must now once again worry about people entering their schools with guns.

October 30, 2021

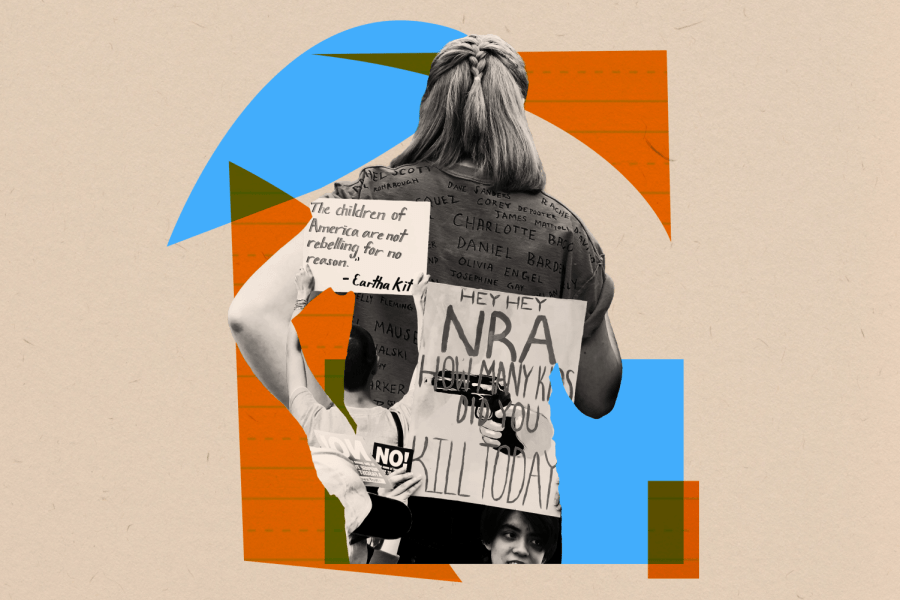

The last time I had hope that America would reevaluate its culture of shooting up children was in 2018, right after the Parkland massacre. The movement to enact gun control laws was led by kids, the same kids who witnessed their friends being murdered and endured the trauma of recounting their stories again and again. I remember thinking to myself, “Surely, lawmakers can’t look at the sobbing faces of these teenagers and do nothing.”

They didn’t do nothing, but it wasn’t enough. And it happened again. One of the more recent incidents was in Houston, Texas, at YES Prep Southwest Secondary School. The Oct. 1 shooting may not have resulted in any fatalities, but the experience will remain with these young students forever. And it is not a unique case. This was the 18th school shooting of 2021, and this year’s number already surpassed the 10 recorded cases in 2020.

Despite its setbacks, many students found safety in remote learning. The pandemic put the threat of in-school violence on hold, but with the return to in-person learning, that threat is once again pertinent. Without proper funding, schools lack the agency to protect their students. Through counseling services and violence prevention programs, schools can fill the gaps that gun regulation laws missed.

When the government fails, the burden falls on these community leaders to fill the gaps.

Schools are still ill-equipped to deal with this peril. Students have lacked access to in-person mental health resources for so long — it is now up to school districts to re-establish support systems and recreate communities in which students feel safe asking for help with mental health challenges. This requires adequate funding from state and local governments. Given that two-thirds of public school students already face a funding gap, it is imperative that state legislators allocate more mental health resources to students to ensure their safety and well-being in and out of school.

It is not enough to simply state that resources are available; staff members need to actively have conversations about the importance of mental health with their students. Counselors, psychologists and therapists need to be in every school. Furthermore, teachers must implement some form of social-emotional learning into their lessons. When the government fails, the burden falls on these community leaders to fill the gaps.

However, additional measures taken to help students in need cannot come at the cost of teacher burnout. Counselors and licensed psychologists can support teachers in this endeavor, but the reality is that 25% of high schools have no counselors. These staff members are essential. According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), students are 21 times more likely to seek out school-based medical services than services offered anywhere else.

One measure taken by schools that has proven effective is the implementation of violence prevention programs. One such program, School-Wide Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports (SWPBIS), has been incorporated into Illinois’ school curriculum. The program contains three tiers: a clear education to the entire population of students on what appropriate behavior looks like in the classroom, a universal screening and monitoring for students deemed to be at-risk for exhibiting violent behavior, and an individual intervention and functional behavioral assessment for students who have already exhibited violence. Studies have shown that students experienced fewer disciplinary referrals and increased academic achievement, as well as an increase in perceived safety, due to the implementation of this program.

I have had experience with a violence prevention curriculum called Second Step, implemented in my elementary school after a student brought a knife onto school property. The curriculum we were taught focused on bullying, peer pressure and scenarios with moral dilemmas. In one scenario, students were asked to discuss what they would do if they saw that their peer had brought a gun to school. In some studies, Second Step showed results of decreasing antisocial behaviors and peer problems.

When students are robbed of these resources, they are also robbed of their physical safety and emotional wellbeing. They are robbed of their futures.

Warning signs, however, can be hard to spot in the classroom. Only 32% of school shooters faced disciplinary problems prior to the attack, while 78% of perpetrators had a history of attempted suicide or suicidal ideations. Shockingly, only 34% received mental health evaluations. The Safe Schools Initiative Report indicated that 71% of perpetrators experienced severe bullying that led up to the attack, whereas the other two leading causes of school shootings were noncompliance with or the side effects of psychiatric medication. If monitored properly, children with these experiences may not have ended in tragedy.

The necessity of bringing these resources into schools calls into question how the role of educational institutions should change and whether they can, given their limited funding. Teachers are already overworked and underpaid, and often have to contribute their own money to provide their students with enriching activities.

When students are robbed of these resources, they are also robbed of their physical safety and emotional wellbeing. They are robbed of their futures. When such high numbers of students do not have access to these support systems, it should not come as a surprise when tragedy ensues.

Nikolay Stoykov • Jan 8, 2022 at 2:17 pm

It was an eye-opening article. Over 70% of the cases of school violence can be associated with bullying or psychiatric problems, not with gang activity! This may be the result of effective law enforcement, but it clearly indicates that resources should urgently be provided to promote mental health and behavioral counseling and education in our schools!