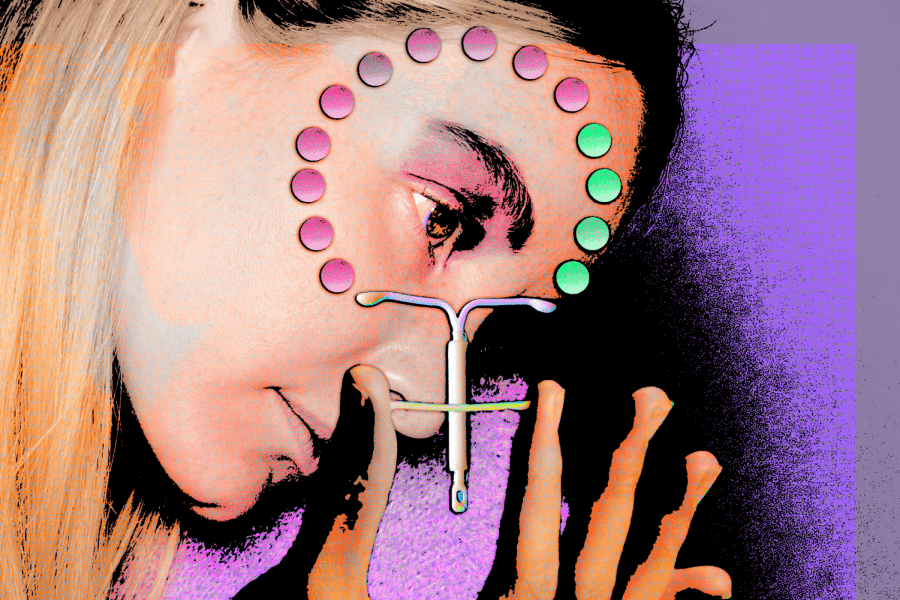

Baring It All: The Injustice of Female Birth Control

Women deserve changes in the social stigma and lack of research surrounding contraceptive care

October 25, 2021

My mind and body haven’t been my own for over a year. Violent mood swings sweep over my mind while random cramps rack my body. Migraines last for days, inducing the ingestion of troubling amounts of pain relief medicine and caffeine. The semi-regular shedding of my uterine lining every month since I was 13 has disappeared completely, leaving me at a loss without this bodily ritual.

I was 19 when I first went on birth control, older than most women who get contraceptives, and I still wasn’t prepared for the extreme changes my body has undergone over the past year. I studied up on different contraceptive options and consoled myself with the knowledge that over 47 million women a year — or about 65% of all U.S. women aged 15-49 who use a contraceptive method — took the same step I was taking.

When I confidently strolled into the gynecologist’s office barely over a year ago, I didn’t realize that there were large parts of this process not explained in Google searches or superficial conversations about whether I’m better at taking pills on a schedule or if it’d be more effective to have an inch-and-a-half rod inserted into my arm. My concerns about possible physical, psychological or physiological changes were brushed off by my doctor with a blasé, “You’ll be fine! Most people are.”

Birth control is not given a place of proper discourse in society.

I was fine. And I am fine. I was one of the “lucky ones” — though my reactions to birth control sound dramatic, none of them truly inhibit my ability to live a normal life, and I didn’t have to switch contraceptive methods because mine was intolerable, unlike many women who have to “shop around” to find compatible birth control. I was able to select the kind of birth control I wanted and wasn’t coerced into choosing one I didn’t think would be a good fit, another often-overlooked issue related to women’s reproductive health.

But I’m frustrated by what is not discussed, what is downplayed and dismissed. Getting birth control is no small act. Yet, the process is often pushed into the shadows, marked as taboo in family discussions, scorned and used to judge women for being sexually active.

Contraceptives, or any means used to prevent the sperm from reaching the egg, are a form of birth control. Though contraceptives include everything from condoms to hysterectomies, hormonal pills (“birth control pills”) and other hormone-based means of regulation are some of the more widely used contraceptive methods and have even been labeled as a “lifestyle drug.” According to a report by Rachel K. Jones of the Guttmacher Institute, “14% of pill users—1.5 million women—rely on them exclusively for noncontraceptive purposes” and “more than half (58%) of all pill users rely on the method, at least in part, for purposes other than pregnancy prevention—meaning that only 42% use the pill exclusively for contraceptive reasons.”

Doctors, who are responsible for guiding women through this process, often don’t have these answers themselves.

Birth control is not given a place of proper discourse in society. It’s relegated to whispered discussions in school hallways between young girls and searches on private browsers for answers about whatever symptom that’s suddenly manifested after getting on the pill. If you aren’t bleeding abnormally or in incredible amounts of pain because of your birth control, the other side effects — like bleeding more or less or not at all, weight gain, more or less painful cramping, nausea, and headaches — however persistent, are just written off as “part of the experience.”

But they shouldn’t have to be part of the experience. It’s scary to go through these changes, especially when other women don’t seem to go through them. As a young woman on birth control, the people I felt I could confide in were my other young friends, who could empathize with me about the changes I was going through but who could not provide any clarity on why a drug meant to prevent pregnancy was affecting so many other parts of my body.

How do we live in a society where it’s just accepted that for women to protect themselves reproductively, they have to compromise their mental and physical health?

Though women go on birth control for many reasons — pregnancy prevention being just one — there is little discussion about the widespread effects of birth control and even less discussion about why there aren’t separate treatments for preventing pregnancy and soothing painful menstrual cramps, two disparate yet common applications of the pill.

Doctors, who are responsible for guiding women through this process, often don’t have these answers themselves. Determining amenable birth control has been described as a process of “trial and error,” partly because the trial and error data gathered through research trials is absent, leaving doctors with a dearth of large-scale, detailed and accessible data to draw upon when advising women about birth control. The lack of data on birth control is compounded by how generally birth control is prescribed — for everything from painful menstrual cramps and endometriosis to severe acne and anemia prevention.

Contraceptives, especially hormone-regulating ones like most birth control options, often affect other systems of the body. A 2020 study demonstrated links between women who take the pill and a smaller hypothalamus, the structure in the brain primarily responsible for regulating appetite, body temperature and emotions. Another study from 2017 found that women taking oral contraceptives experienced a “blunted stress response,” “highlight(ing) that the effects of the birth control pill go far beyond sex hormones” and extend into other systems of the body. The cortisol levels of women taking oral contraceptives actually resembled “the pattern that you see in people with PTSD and people who’ve experienced chronic trauma.”

Why are we okay with this? How do we live in a society where it’s just accepted that for women to protect themselves reproductively, they have to compromise their mental and physical health? If it were men who were expected to be on birth control, I doubt society would stand for it.

In fact, that’s the primary reason that male birth control isn’t on the market, despite numerous successful and safe trials — because men don’t have to contend with the possibility of pregnancy, there’s “a different risk-benefit analysis when it comes to men using a contraceptive,” one in which “male contraceptives aren’t really allowed to have side effects.” Simply because women’s bodies contain the mechanisms for growing fetuses, the responsibility of controlling the means of reproduction fall upon us. If women are to be saddled with this responsibility, the least society can do is make birth control less of a wild (and sometimes traumatic) card for women.

So why isn’t there already more research into better birth control to protect women? The unfortunate answer is that lessening the burdensome side effects of birth control for women is just not worth it to scientists or investors. A Bloomberg article from 2019 broke the news of a gel that would act as a “sex-on-demand contraceptive for women,” comparable to the ease with which men use condoms as contraceptives, but the product stalled at the production stage because of low revenues and red tape.

My symptoms, as trivial and common as they may seem, should not have to be a part of my daily existence in exchange for avoiding pregnancy.

Its story emulates those of other hampered improvements to birth control, as contraceptives are not as great a source of revenue as, say, cancer or Alzheimer’s treatments. Additionally, very little revenue from contraceptive sales goes back into research on the subject; where most other drugs have roughly 50% of the revenue going toward research and development of the treatment, contraceptives stand at only 2%.

Research on birth control is also not invested in because, at the end of the day, birth control does the bare minimum it was designed to do, side effects notwithstanding: It successfully prevents pregnancy. The authors of the article in The Conversation further explained that “Many women will also continue using birth control despite side effects because they don’t want to get pregnant — so many developers may not see improving formulations as necessary.” “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” — that’s how the saying goes, right?

By not improving birth control so its application is more targeted and it creates fewer problems than it solves, we’re further contributing to harmful stereotypes and expectations that women can and should handle more pain than men. This simply isn’t true: There is no world in which a woman should move through her life in pain, however minor or slight, simply because she was prescribed a pill to prevent pregnancy, alleviate acne or relieve cramps. My symptoms, as trivial and common as they may seem, should not have to be a part of my daily existence in exchange for avoiding pregnancy.

We need more transparency when it comes to contraceptives.

I’m not arguing that women should stop using contraceptives or disregard all of the benefits that have come from them — having control over their reproductive systems has allowed women more freedom to choose the futures they want.

But not having information about birth control readily available, disseminated and destigmatized for women is a public health risk that should not be tolerated — and that isn’t tolerated for the opposite sex. Women shouldn’t have to put themselves at such risk just to ensure they won’t become pregnant or to mitigate acne or to help control depression.

We need more transparency when it comes to contraceptives. If the burden’s going to be put on women to look out for their sexual and reproductive health, then we need to normalize talking about the process and the side effects, big and small. We need more research to make birth control safer, more predictable and more targeted to the issue it’s meant to address — pregnancy prevention — rather than being a cure-all for a myriad of other medical conditions.

We need to stop forcing women to settle for the bare minimum.

Emiliana • Oct 28, 2021 at 5:09 pm

AMEN.

Is sex worth all this? Is HE worth side effects?

It’s kinda crazy what women will do to have sex with men/love. My unpopular opinion is to skip the hassle. If he can’t pull out, don’t put out (if he is bad at it? Condom then). Or he needs a snip/snap.