Live Music Remains Unconquered

Juilliard composer Anthony Barfield conducts ‘Invictus,’ a social-distanced, multi-genre brass piece

COURTESY OF ANTHONY BARFIELD

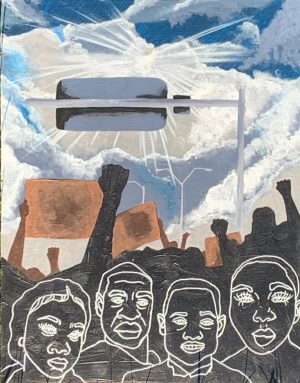

Musician Anthony Barfield used his experience in various genres of music to create “Invictus,” which was performed live on the Josie Robertson Plaza.

October 14, 2020

Conductor Anthony Barfield showcased “Invictus” at Lincoln Center on Aug. 7 as an ode to the city and its people during a time marked by COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Alongside 15 brass instrumentalists, Barfield told the story of New York through the brass composition by drawing from elements of gospel, jazz, classical and hip-hop traditions. The piece, just like the city, is diverse within itself.

Due to the ongoing pandemic, the city’s performing arts spaces had been closed for six months, but the warm and sometimes brassy, sometimes mellow tones of Barfield’s piece rang through the Josie Robertson Plaza at Lincoln Center.

The musicians featured in the piece all come from different genres and experiences, so their unique perspectives of the instrumentation come together to form “Invictus.” This was the first time in history that performers from the MET Orchestra Musicians, the New York Philharmonic, The Juilliard School, Jazz at Lincoln Center, New York City Ballet Orchestra and the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra performed together.

In a time when we must be social distanced, Barfield figured out a way to create live music in the same space as others.

Any person, no matter their education level or income, should be able to get some emotion and expression out of his music, even if they’ve never studied music before.

As a Juilliard alumnus and faculty member, Barfield is no stranger to the Lincoln Center area. According to his website, Barfield went to Juilliard for trombone performance. Living as a music student in the city, he was able to take on many opportunities to perform at places such as Carnegie Hall, Dizzy’s Coca Cola Club and the Kennedy Center.

On the Josie Robertson Plaza, the musicians stood 12 feet apart in a half-circle with Barfield at the center, 40 feet from his musicians. For Barfield, this was the first time in months that he had been able to work with other musicians. “Bringing art back to the city is fun, but to be able to collaborate and feed off of each other again — musicians and artists thrive on collaboration,” he said. The video shows how fruitful it can be for musicians to work together now.

In his performance video, Barfield said that “Invictus” is supposed to be about “New York in its current state with Black Lives Matter, dealing with COVID-19 — the uncertainty of it all.”

Performing in Lincoln Center has a heavy historical significance. That land, once occupied by working-class and low-income Black and Latinx folks, is now a place where upper-class white folks indulge in fine art. Barfield paid respects to this history when creating the piece: “When I was writing something, I wanted to make sure that it was something for the people.”

In making his piece accessible to all audiences, he applied both his hip-hop and classical musical backgrounds. His career expands beyond composing and producing for ensembles; he also produces for mainstream artists. His work is featured in songs by Chris Brown, Lil Wayne, Young MA and Trippie Redd.

Working with different types of musicians, Barfield noted that “in the classical world … people who understand those mediums want to intellectualize that particular art from the neck up — they want to understand what goes into making that piece of artwork.”

On the other hand, “the rest of the world wants to intellectualize from the neck down — meaning they like the feeling of the piece of work,” not the thought process that goes into creating the music.

Barfield consciously made his melody both “strong” and “memorable” because he wanted the music to be accessible to everyone. Any person, no matter their education level or income, should be able to get some emotion and expression out of his music, even if they’ve never studied music before. “I can’t tell you the number of times I have played a beat for classical musicians and they’ll pick it apart — ‘Ah, man, you did this harmony and this groove.’ But then I’ll play it for my mama or my friends and they’ll just groove through it,” he explained.

With “Invictus,” any way of interpreting the rhythm and melody is acceptable to Barfield — he made it with any audience in mind, from hip hop fans to orchestra-goers.

“I don’t want people to support me; I want them to have conversations about Black Lives Matter. Make sure that people can actually do research to learn more about Black history and then have a conversation about it.” Anthony Barfield, “Invictus” composer

As a resident of Washington Heights, he saw firsthand the devastation that the coronavirus brought to the neighborhood. Residents there, unlike those who retreated to their summer homes in Connecticut whom Barfield considers “not real New York,” faced the virus head-on. “There are a lot of people out here that are struggling. Not just with losing jobs, but also that anxiety and depression that goes with that. Uncertainty is a real thing,” he said. Life is never easy as working-class people in New York, especially during the pandemic.

As an artist, he knew many people in his field who could not find jobs “and made the decision to change careers — orchestras are shut down; Broadway is shut down; there are no gigs.”

Barfield knows that music is not for a small, select group of privileged people. He noted that the Black Lives Matter movement has allowed “organizations to start hiring more Black musicians and composers.” In his own career, Barfield has “received a lot of offers” from historically white performance centers after “Invictus” was aired on the Lincoln Center website.

Barfield has said, “I don’t want people to support me; I want them to have conversations about Black Lives Matter. Make sure that people can actually do research to learn more about Black history and then have a conversation about it.”