‘How to Defend Yourself’ Is the Play Gen Z Needs

The radical, visceral and emotionally honest production sheds light on topics deeply felt but rarely spoken

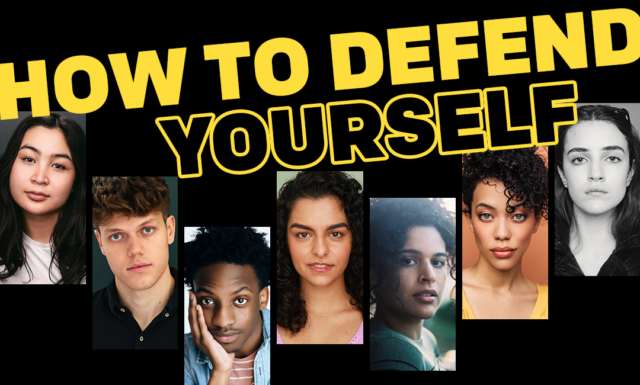

COURTESY OF NEW YORK THEATRE WORKSHOP

“How to Defend Yourself” ran from March 13 to April 2 at the New York Theatre Workshop.

April 11, 2023

Content Warning: This article contains spoilers for the play “How to Defend Yourself” and features discussion of sensitive topics regarding sexual assault and rape.

In the opening minutes of “How to Defend Yourself,” five short bursts of speech veiled in snarky humor provide the audience an impression of the emotion that’s to come.

“I wish girls fought more,” college first-year Diana (Gabriela Ortega) says to her best friend Mojdeh (Ariana Mahallati). “Like beat the shit out of each other for fun. I wish that was like a socially acceptable thing to do. Fight club, you know? If it was me and you, I think I’d win.”

Written by Liliana Padilla and co-directed by Padilla, Rachel Chavkin (“Hadestown”) and Steph Paul (“The Last Match”), the play takes place in an unnamed American university filled with sports, fraternities and sex. It tells the story of two students, Brandi “B” (Talia Ryder) and Kara (Sarah Marie Rodriguez), who start a self-defense class after their close friend is raped by two fraternity boys.

As Mojdeh and Diana prepare for rush week and adjust to college life, the story becomes increasingly painful when they join B and Kara’s class, navigating the effects of the trauma that blanket their entire school. Kara begins to find fault in B’s militaristic self-defense training approach, and it becomes apparent that trauma not only affects one person but has a serious second-hand impact on those close to the person.

In an overstimulating immersion of lights, confused speech and digital vocal manipulation, B is brought to screams as she accepts that even doing the most you can can’t save the world.

They are later joined by Andy (Sebastian Delascasas) and Eggo (Jayson Lee), two caring yet at times painfully unaware fraternity boys, and Nikki (Amaya Braganza), an initially shy yet strong-willed student.

Although the work may be more aptly titled “How to Defend Yourself (From Men),” Padilla finds a place for men in Andy and Eggo, who often encourage the play’s progressive discourse. At one point, Eggo offers a semi-monologue on his struggles to be a conscious lover in the fast-paced environment of fraternity parties, where sex so often happens without thorough communication and can leave consenting partners confused and unfulfilled. Diana and Kara respond with the brutally honest revelation that sometimes what we want is to be desired and to be out of control. Eggo, frustrated by his unpleasurable relationships and Diana and Kara’s seemingly contradictory feelings, responds by asking what the difference is between “surprise and assault.” The cast is unable to answer.

Throughout the play, the audience is presented with equally difficult discussions of the carnal nature of sex and how it often clashes with the innocence of our inner child and our dreams of falling in love. Although Padilla perfectly encapsulates modern concerns surrounding sex and relationships, this moral and sociobiological dissonance is left largely unresolved.

In addition to its painful topics, “How to Defend Yourself” provides a space for honest and direct discussions about the pleasures and naivety surrounding sex, as they relate to everyone, no matter how much experience they have.

“How to Defend Yourself” presents so many topics that every Gen Zer seems to recognize and feel for yet doesn’t have the words nor the platform to talk about.

The play certainly isn’t solely depressing; it’s often uplighting. About halfway through the play, Eggo performs a dance sequence which offers a soothing break from the traumatic subject. Indeed, the play offers hope, but the “answers” provided are less physical than they are spiritual, less tangible than the lingering immediacy of traumatic experience.

Pandilla does not turn away from taboo. As Eggo and Andy discuss the circumstances surrounding Susannah’s rape, Andy reveales that he had witnessed — and was turned on by — what he would later find out to be a rape in progress, or perhaps even in a moment when it was consensual. His shame is echoed later by Diana when she tells Kara that she too was turned on after hearing the news of Susannah’s rape.

What we feel is rarely what we say, and it regrettably takes pain, or an overwhelming torrent of emotion, to blow the cap on the shameful feelings we keep bottled up. Throughout the play, the characters present the audience with similarly shameful, sometimes angry and tearful beliefs about sex, and the audience is left to ponder what they, and what the people they are intimate with, keep hidden.

The play’s ending begins with the recognition of the all-too-confusing and hedonistic reality of sex. All of B’s friends end up rejecting her self-defense class and leave her to break down. In an overstimulating immersion of lights, confused speech and digital vocal manipulation, B is brought to screams as she accepts that even doing the most you can can’t save the world.

In a sudden change of scene, B’s friends burst through the door and the audience is brought to a fraternity party where, in a soberingly ironic twist, B is effectively assaulted by her friends who lift her up and force her to drink from a keg. She then embraces the party lifestyle.

Through a vignette-like array of scenes in which the cast provides their friends with the respective social environments they desire, the play seems to say that the most we can do is be attentive to the needs of our friends and support them in doing what’s good for them.

The play’s weaknesses lie here, in this seeming lack of a resolution given to the work’s central dilemma: how to process the trauma of rape without falling into tropes of pity and victimhood, while at the same time honestly analyzing its immediate and ongoing consequences.

While it is certainly a sign that happiness can and should be found after trauma, this final vignette seems more like an ignorance of the problems at hand rather than a thorough processing of life after trauma. The production would have been aided by further dialogue discussing how to feel deserving of happiness, yet the final moments offer a sign of rebirth.

The final scene features a young girl peeking her head through the door as she watches the group dancing sensually at a fraternity party. Suddenly the group leaves, the lights darken, and the young girl is left alone on stage, wandering. The lights go on, and the group comes out with a birthday cake, one candle lit, singing “Happy Birthday” to a child Susannah. Among the final lines are B saying, “Susannah, Susannah?” as the girl blows out her candles.

The final scene seems to declare innocence as the most present, if not the most important, aspect of human nature, though it is rarely seen.

“How to Defend Yourself” presents so many topics that every Gen Zer seems to recognize and feel for yet doesn’t have the words nor the platform to talk about. This is equally as sobering as it is emotional. The production’s use of an intimacy coordinator (Ann James) should be of note as theater productions strive to tackle real yet painful and oftentimes triggering subjects. “How to Defend Yourself” is set to be a guidebook for how to tackle such topics in an honest, relatable and progress-oriented manner.

“How to Defend Yourself” opened for previews on Feb. 22 at the New York Theatre Workshop and held its opening night on March 13. The production closed on April 2.