Revitalizing a Family Tofu Business: Fong On Caters to a New Generation

Paul Eng inherits a resilient force of Chinatown and adapts it to an ever-changing food industry

Fong On, formerly a Mott Street staple, was reopened by Paul Eng in 2019. Now, it provides authentic Chinese food to all people who visit.

August 25, 2021

There are many challenges to starting a family business, but there are even more when inheriting one.

Paul Eng is the successor to Chinatown’s oldest family-owned tofu shop, Fong On. The store was a community staple on Mott Street until 2017 when Eng’s brother, David Eng, decided to permanently close it.

Eng reopened the store in August 2019 with hopes to expand Fong On’s reach beyond Chinatown. He also confronted the need to modernize equipment, prioritize new menu items and continue to cater to Chinatown locals.

Preservation of the Family Business

Growing up, Eng and his four brothers all worked at the store. He described it as “a source of employment for multiple generations of the family.”

Unlike David, Eng decided to pursue other careers instead of staying at the family business. “Because I was the youngest of the family, I was able to do whatever I wanted to,” he said.

He earned a degree in architecture, played guitar in a band called Piss Factory and moved to Moscow where he became a photographer. There, he met his wife, Marina, and they had two children.

It was the enormous responsibility of starting a family and the need for financial stability that led Eng back to the family business. “I came back for the same reason my grandfather and father did: to support my family,” Eng said.

“People bemoan the loss of mom-and-pop stores, but essentially, we still are that.” Paul Eng, owner of Fong On

The workplace culture of Fong On still resembles a family business. Eng’s brother and wife occasionally help oversee production in times of need, and all employees are treated as part of the family.

“I really like the people here; they are all really nice and easygoing,” Jolie Kwok, a recent hire, said.

Madeline Lee, an employee at Fong On since the 2019 reopening, said the team is like a family and she enjoys working with the customers because “everyone is friendly.”

“People bemoan the loss of mom-and-pop stores, but essentially, we still are that,” Eng said.

“I always thought at some point, it should be much more welcoming and open.” Paul Eng

A Change in Clientele and Production

Up until 2017, Fong On operated out of storefronts on Mott Street — first at 43 Mott St., then at 46 Mott St. under the name “Fong Inn Too.” The properties were sold in 2017, but the family still owned property at 81 Division St., where the tofu factory was located. This became the site for the newly reopened Fong On in 2019.

“The old store was dark, dingy and dirty, and no one spoke English,” Eng said. “I always thought at some point, it should be much more welcoming and open.”

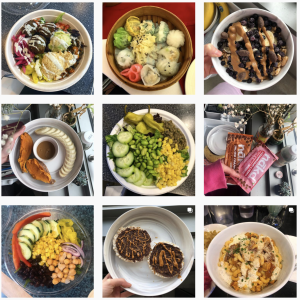

Eng designed a modern storefront utilizing his experience in the art industry, which gained attention from a vegan food Instagram account with more than 50,000 followers.

View this post on Instagram

Now, Eng said Fong On’s customer base is much younger and many non-Chinese people come to the store — especially on weekends when there are tourists in the neighborhood.

The shift in Fong On’s demographic is attributable to the store’s new emphasis on ready-to-eat food such as tofu pudding and rice cakes.

“Food is the first thing to become global,” he said. “We’re not altering the food to fit anybody’s taste buds; we’re educating other people to eat our food exactly the way it is.”

Fong On’s most popular product since the reopening is its tofu pudding, which can be garnished with toppings such as fried shallot or aiyu jelly. Eng said he got the idea to add toppings from a recent trip to Taiwan.

“When they offered it with toppings, I was like, that’s weird. Literally after the first bite I felt the lightbulb go off like ‘Bing!’ This is something we can do,” he said.

Eng said he chose to prioritize ready-to-eat food for the store’s reopening because the migration of Chinese immigrants to the outer boroughs.

Before the store’s reopening in 2019, Fong On excelled in providing the Chinatown community with wholesale products such as tofu, rice noodles and rice flour for cooking and baking.

Eng said he chose to prioritize ready-to-eat food for the store’s reopening because the migration of Chinese immigrants to the outer boroughs and the emergence of Asian supermarkets over the last 20 years drastically impacted Fong On’s business.

“Why would people come to a small store out of their way to buy a block of tofu that lasts a week when they could buy it in a package that will last two months at a supermarket?” he asked.

During Chinese New Year, Eng said the store used to sell more than 20,000 pounds of wet rice powder a week. The powder is used to bake traditional holiday cakes, and the abundance of sales alluded to the size of the Chinatown community.

Slowly, sales dwindled to only 20,000 pounds a season as supermarkets introduced dried variations of the powder that can be stored for longer. Business continued to drop as longtime customers moved out of the neighborhood.

“It is indicative of who knew how to use the powder either dying or moving away,” he said. “Now, we don’t sell it.”

Local people continue to come to the store, but Eng said “they are very few and definitely declining.” He understood, however, that a change in how Fong On conducted business was necessary.

“Being one of the oldest businesses in Chinatown, our development sets a path for the community to mimic.” Paul Eng

A modernization of how their products are made was his first step. The store still uses the recipes that Eng’s grandfather developed in the 1930s, who used to grind soybeans by hand, extracting enough milk to press one block of tofu at a time.

Eng acknowledged that it is not an efficient business model for the 21st century: “We’re not going to hand grind everything.”

New equipment and processes were budgeted based on the store’s space restrictions and a desire to modernize. Steaming cabinets replaced 10-foot wok lines for the heating process and pneumatic presses with 220-volt, 300-watt motors took over the work of pressing the tofu.

“Sometimes people have this nostalgia about how our store was, but it was never stagnant. It has been around since 1933 and has always been changing,” Eng said. “Being one of the oldest businesses in Chinatown, our development sets a path for the community to mimic.”

The Pandemic and Beyond

After maintaining enough business to survive for 88 years, the coronavirus pandemic hit within the first year of Fong On’s reopening. Eng seemed unfazed.

“We’ve been through everything: blackouts, arson, armed robbery, extortion, embezzlement, floods, electrical fires, grease fires, you name it,” Eng said. “We’ve survived worse.”

Eng said the impact of the pandemic on the business was “fortuitous” since the store was in “its infancy,” and the restrictions and closures allowed him to slow down and make adjustments.

“The food and the culture should be mixed elsewhere; it is the key to its survival.” Paul Eng

“The infancy has stretched even longer because of the pandemic, but I have no doubt going forward it will be more successful because time has proven we are stable and cover ourselves,” he said.

Eng said he wants to expand Fong On in the future and add another location, though he still wants to keep the company small enough to maintain his hands-on business approach.

To reach new customers and allow many different people to try their products, Eng said the next location would not be based in Chinatown.

“The food and the culture should be mixed elsewhere; it is the key to its survival,” he said.