Karens and Congee: Asian Foods Do Not Need White People’s Input

Karen the Congee Queen highlights an ongoing problem of cultural appropriation in the food industry

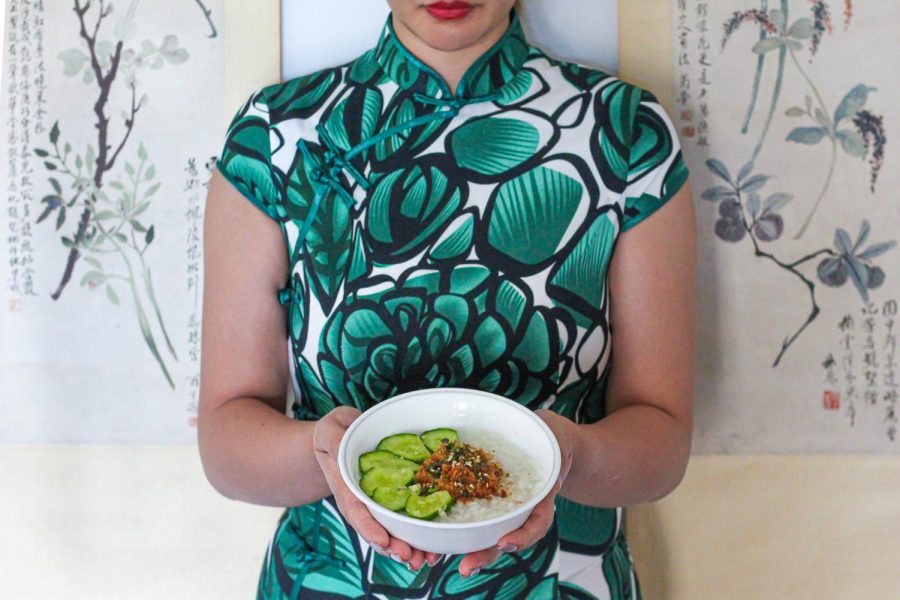

Traditional Taiwanese congee, served one way with pork floss and garlic cucumbers, unlike the poorly appropriated blueberry oatmeal.

July 31, 2021

With the mid-May sun setting over the Hudson a few avenues behind me, I sat eyeing the tiny bowl of soba noodles placed on the white tablecloth in front of me and immediately regretted my choice. The noodles, which I could have gotten for less than half the price at any other Japanese restaurant, would be washed down in two to three bites. I smiled politely at my best friend’s parents, who had invited me to dine with them here at 15East @ Tocqueville. But as I dove into my meal, I said a silent prayer that my roommates hadn’t yet finished the tater tots we keep stocked in our freezer.

They hadn’t, thank goodness. Seventy dollars and several stops on the R train later, I filled my still-empty stomach with greasy bite-sized potatoes and wondered why I expected anything else when I knew we were going to an “Asian fusion” restaurant.

Many popular restaurants around New York fall under the category of Asian fusion or “upscale” Asian restaurants. While some may be quite harmless, many others contribute to the sentiment that Asian foods need to be elevated or Westernized in order to make them trendy. But why do Asian foods need fusion or elevation in the first place? Who decided that Asian foods needed to be tweaked or made “fancier” in order to be more marketable and, therefore, more enjoyable?

It’s not that I claim to be a culinary expert, nor have I tried every Asian fusion restaurant out there. My general discomfort with these restaurants, however, stems from the fact that they tend to follow a pattern of combining one or more types of Asian cuisine with a European or American (in other words, Caucasian) cuisine whose techniques are considered “classic” and “fundamental” for respectable modern chefs. By fusing together Japanese cuisine with French, for example, a restaurant attracts customers with the promise of something different, something cultural (Japanese), while using the Western element to overcharge guests for something as simple as tofu.

Exhibit A: 15East @ Tocqueville charging $26 for a block of flavorless tofu as an entrée, served cold.

This is far from the only example. With establishments like the white-owned Tao Downtown — one of the highest-grossing non-chain restaurants in all of New York City that sells low-quality, overpriced pan-Asian food — along with other restaurants creating bizarre combinations like Cuban and Chinese cuisines, the food industry is constantly sending the message that non-European cuisines are not good enough to stand alone nor escape unnecessary embellishment.

In other words, the touch of a white person apparently elevates cultural foods that had previously struggled to find their position in fine dining. Not only that, these same cultural foods have long been deemed “disgusting” by the same group of white Americans who are willing to buy the Westernized versions. Recently, James Corden’s Late Show segment titled “Spill Your Guts or Fill Your Guts” came under fire for mocking Asian delicacies in popular YouTube videos, with some boasting up to 60 million views. While this much-needed criticism for Corden is new, the practice of bullying Asians for their foods is unfortunately not.

Fast forward a couple of months: I’m scraping up the last of my congee with preserved duck egg, a popular porridge dish made from rice, in my uncle’s house in Shanghai. I scroll through social media to find many Asian-American activists enraged about the latest crime in cultural appropriation, committed by some white woman of the name Karen Taylor who labeled herself “Congee Queen.” I wish I could make this type of irony up.

Congee does not need Americanization for it to be enjoyable or respected.

Taylor had started a business named Breakfast Cure. On its website, which has since been edited, Taylor described her business as a “gourmet, foodie version of traditional congee… deliciously designed to delight your modern palate.” As many have already pointed out, thinking congee needs to be “gourmet” and adapted to a modern, Western audience is incredibly insensitive, if not flat-out delusional.

Congee does not need Americanization for it to be enjoyable or respected. Nor does it need modernization — the very suggestion of modern implies that such an ancient Asian dish no longer serves a purpose in our diet, which could not be further from the truth. This is the dish that my parents have always had for breakfast. It’s the dish that they made me when I was in bed sick with a fever. It is what we ordered alongside dim sum on Sundays. It is something I can get for two dollars down the street from my childhood home. It is a dish that has a history longer than the existence of the United States. It has a legacy that needs no assistance from a white woman who labeled her extreme cultural appropriation a “business.”

The atrocity, unfortunately, does not end with her description of her company. Taking a look at Breakfast Cure’s website, I find that Taylor has manipulated congee into something unrecognizable — something that resembles, god forbid, oatmeal. The flavors could not be further from traditional congee, incorporating ingredients like apples, cinnamon, blueberries, ghee, coconut cream and pineapple.

The incorporation of fruits into congee begs the question of whether this Karen has any real enthusiasm for congee. To claim a traditional dish enjoyed by many Asian countries needs improvement is rude enough as is. To treat it as glorified Quaker oats is a whole other level of disrespect.

Taylor, then, is more interested in using the association of Asian cultures with the “exotic” to turn a profit than she is in the actual congee dish.

On top of that, each packet, as in one serving, is priced at $14.95, which is enough money for me to buy the ingredients to make congee that will last me nearly two months. Alternatively, it’s enough to buy 50 packets of flavored oatmeal, which is essentially what Breakfast Cure’s apple cinnamon congee is. Taylor, then, is more interested in using the association of Asian cultures with the “exotic” to turn a profit than she is in the actual congee dish.

Another aspect of the issue is business owners can get away with ridiculous prices as long as they market their food as healthy or even “healing,” as Taylor does. Diet culture is toxic for many reasons, including but not limited to fostering eating disorders and profiting off of fads that convince people their body can sustain a no-carb diet. Spoiler alert: it can’t.

If anything, Breakfast Cure is proof that diet culture has gone way too far. On their website under a link titled “Wisdom of Warmth,” which I couldn’t explain to you even if I tried, the company’s mission statement boasts, “our simple congee method is spreading the wisdom that warm cooked foods heal, soothe, and energize.” Excuse the informality, but …huh? Since when did anyone stop believing in warm cooked foods? Did the raw food fad that was trending a few years back really deceive us that badly?

The best way to value AAPI lives and respect their culture is to support AAPI-owned businesses.

Either way, profiting off of eating insecurities and the appropriation of Asian cultures is inexcusable. The problem, though, goes far beyond this one company. Breakfast Cure may be highly criticized by the media now, but there is a whole pattern of exoticizing and exploiting Asian cuisines that goes unchecked.

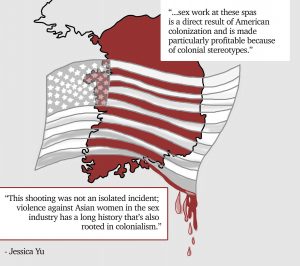

With this year’s extreme increase in Asian hate crimes came a slight increase in awareness of Asian hate as well as advocacy for supporting Asian, Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) lives. As a response to the backlash received in the past few days, Karen Taylor decided to use her business’s profit to give back to the Asian community through donations. Slapping a few charities on the company website, however, does not take away from the insensitive narratives that the very existence of such a company pushes.

The best way to value AAPI lives and respect their culture is to support AAPI-owned businesses without taking up their space with unnecessary renditions of foods that are already perfectly tasty. So, go buy yourself some congee from Flushing or soba noodles from any Japanese-owned restaurant. I promise it will be much more worthwhile.

Grace • Feb 3, 2024 at 6:37 am

I’m commenting because the author mentioned eating congee in Shanghai, and I’m right now in Shanghai. It shock me that the author think it a crime to add fruits or coconut milk into congee. Try it on black rice based recipes. The way the author writes it makes me wonder if they have ever eaten Babaozhou or Labazhou at all. While it’s true that traditional recipes don’t use fresh fruits or coconut milk, there are plenty of modern recipes on so many Chinese recipe websites or social media websites like Xiaohongshu. Also, nowadays we put coconut milk, black rice and fruits into milk tea or other “boba” drinks, and depending on the density, the thicker ones may become quite similar to congee.