QAnon Is Just Another Example of America’s Conspiracy Theory Problem

QAnon uses the same tactics as historical conspiracy groups like the John Birch Society

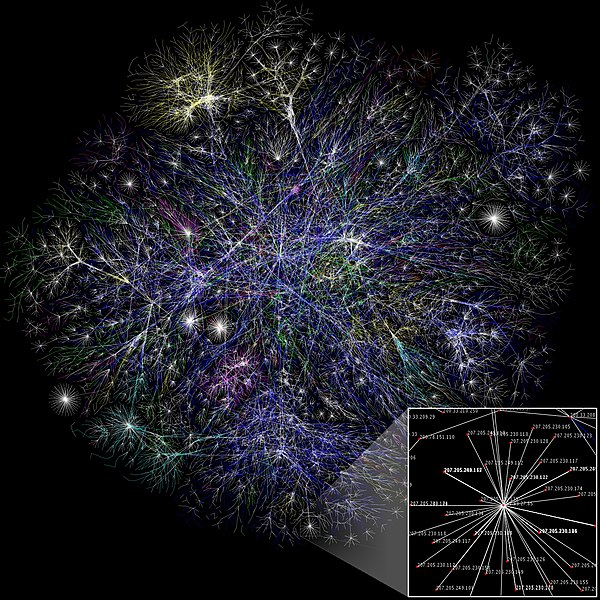

THE OPTE PROJECT VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The dangerous side of social media’s ability to foster far-reaching connection easily comes to light when conspiracies get spread beyond fringe groups and into mainstream circles of trusted friends.

February 17, 2021

The number of think pieces about QAnon, the far-right internet conspiracy theory centered around Donald Trump, has risen dramatically since the Capitol insurrection on Jan. 6. It is undoubtedly a significant and pressing concern for the country. However, much of the discussion around the proper approach to dismantling QAnon presents the group as a distinct foe to be vanquished instead of recognizing it as one component of a larger trend of conspiracy theories.

Several movements in American history have shared QAnon’s paranoid, bigoted, unfounded nature, yet the political establishment has repeatedly failed to take them seriously.

The John Birch Society

One such group that took hold in America in the 1960s was the John Birch Society.

John Birch was an American officer and Baptist missionary who was killed by communist forces in China in 1945, just after World War II. In 1958, an organization dedicated to fighting Communism was founded in Birch’s honor, more than a decade after his death.

The founders included Robert Welch Jr., a retiree from Massachusetts, and Fred Koch of Koch Industries. From the beginning, the Society spoke of “traitors inside the U.S. government” who were conspiring to bring about a New World Order.

Sound familiar? The language is identical to the language of QAnon, despite the half-century of time between them. (Both even use the term “cabal” to describe the perceived threat to society.)

Followers depict the hero as having sacrificed for the cause: They are martyrs who can be rallied around when morale is low.

The John Birch Society warned of the perils of collectivism and urged each member to think for themselves, which consequently bred suspicion throughout the group. That directive is both concrete enough to be actionable (followers can look for clues about public figures and their ties to pedophilia or communism) and amorphous enough to keep people searching indefinitely.

Today, a primary facet of QAnon participation is doing one’s own “research” rather than relying on “the mainstream media.” Both groups have insisted on baseless theories, including mass control through water fluoridation and liberal elites extracting adrenochrome from the blood of kidnapped children.

Another similarity is their dependence on a central iconic figure. Both groups are fundamentally united around a common “savior”: The John Birch Society co-opts the life of Birch, and QAnon constructs a nearly mythical image of Donald Trump that has little to do with his presence in the real world.

Followers depict the hero as having sacrificed for the cause: They are martyrs who can be rallied around when morale is low.

The Role of President Trump and The Republican Party

However, neither Birch nor Trump directly created these movements. Birch was already dead when the John Birch Society began, and Trump has little personal involvement with QAnon. Trump was never on the 4chan message boards where the theories were born, and he never assisted with the internet “research” that was deemed so crucial to the movement.

Trump’s tweets provided fodder for QAnon followers, but the secret instructions they gleaned from his tweets were not suggested by Trump himself. He was merely tweeting, the same way he has for a decade, and the dissection and infusion of meaning happened elsewhere.

Trump is certainly still at fault for encouraging QAnon by addressing them in tweets and speeches, however vaguely, but the shout-outs were more of a last-ditch attempt at seizing undue political power than a long-awaited initiation of his role as a messiah. The insurrection at the Capitol was given a rubber-stamp of approval by Trump moments before, but the throngs who had gathered had done so without his direction. He only pulled the trigger on an already-loaded gun.

McConnell and others like him approach QAnon with the assumption that the Republican Party is going in one direction and factions like QAnon are a detour. But by all accounts, QAnon is where the Republican Party is heading.

Clearly, QAnon is not the first of its kind. Mitch McConnell has acknowledged the similarity and has likened QAnon to a “John Birch Society problem” within the Republican Party that must be reckoned with. But McConnell and others like him approach QAnon with the assumption that the Republican Party is going in one direction and factions like QAnon are a detour. But by all accounts, QAnon is where the Republican Party is heading.

In recalling the John Birch Society, McConnell said the quiet part out loud: He admitted that the Republican Party has a recurring problem within its ranks that leads to real-world consequences when allowed to fester. The John Birch Society still exists, and recent reports that it is “making a comeback” signal a conservative embrace of conspiracy theorists.

Those in the Republican Party who claim that these groups do not represent “real” conservatism have ignored several opportunities to snuff them out. Even in the past when there was more resistance to right-wing conspiracism, outright condemnations were few and far between. When denouncement of groups including the KKK was proposed at the Republican National Convention in 1969, it was immediately shot down.

The Role of Social Media and The Internet

Given the precedent set by the John Birch Society, it is not useful to blame QAnon solely on the internet. However, it is true that online platforms have hastened its growth. A lack of useful moderation allows users to share theories and plans as quickly as they can be invented.

The internet is able to accelerate cult development by fostering the development of community. The John Birch Society recruited members through billboards, flyers and newspaper advertisements, all of which require resources and central planning.

However, QAnon is able to reproduce itself instantly and without charge: Members repost unfounded theories all over their social media, believing it is their righteous duty to share the “truth.” The connection for which social media platforms are so often lauded provides a perfect mechanism for QAnon members to convert others, particularly if their followers know and trust them already.

If the conversion fails, no matter: They are willing to lose friends for their proselytizing, having found a sense of community in QAnon chat rooms. The primarily online existence of extremist groups now allows the cause to take over a person’s real life in a way that would have required much more effort in the time of the John Birch Society.

American Individualism

The immediate goal of these conspiracy theorists is to root out “bad actors,” whether it be secret Communists or pedophilic elites, but there is an underlying belief that if every bad guy is defeated, some miraculous new dawn will break in America. This idea that it all boils down to certain individuals, both in terms of who is the enemy and who is the savior, is indicative of America’s long-held reverence for individualism.

Blaming the nation’s issues — whether contrived or real — solely on individuals instead of the system itself has long been part of the larger American ideology.

Groups like QAnon and the John Birch Society let Americans avoid the central causes of the country’s political and economic problems. Followers are led down a conspiracy rabbit hole instead of recognizing that there are societal issues that must be addressed through legislation and economic overhaul.

The phenomenon isn’t new, but the rapid acceleration of QAnon has thrown into relief how underprepared America is to combat it.

The solution is not necessarily to immediately band together with your local QAnon supporter, especially considering the vile rhetoric that can often accompany participation in fear-based cults and conspiracy theories of this nature. Systemic issues require systemic change, which might include educational reform.

It is not a matter of what level of elite institution a person attends — many participants in the riot were wealthy and received higher education — but rather what is taught. America must provide a more robust, unbiased curriculum which covers more facets of American life as well as teaches the need to address systemic issues, not just individual actors.

QAnon has reinvigorated America’s penchant for rampant suspicion guided by bigotry, and its followers have been given license to commit violence by a political party too frightened to denounce their unfounded theories. The phenomenon isn’t new, but the rapid acceleration of QAnon has thrown into relief how underprepared America is to combat it.

The increasingly complex nature of American life, particularly with regards to the vast and unexplored potential of the internet, makes QAnon something to take extremely seriously — even more so now than its predecessors. Theories with no factual basis spread like wildfire, and we have seen how this invention of fantastical realities can turn into real-life violence.

We must stop pretending like disastrous outcomes can’t happen here. We come face-to-face with the hazards of American exceptionalism when we convince ourselves that American conspiracy theories could never descend into something so bad as those of Nazi Germany. Clearly, the foundations of American democracy are not so resolute if they shudder at the hands of QAnon.

hans • Apr 6, 2022 at 7:26 pm

Every single thing JBS foretold has been front page news for 20 years and getting more relevant every day. They got slandered because they covered the ( we shall over come ) movement that overtook Cuba. I never met a racist or bigot in their ranks. But ha , communist is not a dirty word to some of America. And equating them w qnon is false. LIES

Noah Edelson • Mar 24, 2023 at 9:34 pm

Welch, the JBS founder, accused every president after FDR of being a Commie. Thats badshit crazy conspiracy theory. Just like QAnon, who now has the exact same gameplay. “Fight Communism, install Church values in the people, and destroy Democracy- cause ‘The founding fathers preferred a Republic ‘. .. well I got news for y’all. A Republic *is* a centralized Democracy. You put more power in fewer peoples hands. Namely, the elected representatives.

ernie1241 • Feb 18, 2021 at 2:11 pm

@Thomas Tren — The JBS has NOT been “right” by any normal standard of logic or evidence.

Almost the entire conservative movement in the U.S. denounced and rejected the JBS as a “right wing extremist” group that did NOT deal in facts or reality. The most influential conservative intellectual of the 20th century (Russell Kirk) pointed out that:

“Robert Welch…is remarkably ignorant of the nature of the Communist conspiracy which he denounces; and the sound of his own words has led him to the verge of what Burke called ‘metaphysical madness’. Ever since he founded his society he has done more to injure the cause of responsible conservatism than to act effectively against communism…Many members of the Birch Society, I think,…got into the Society without knowing Mr. Welch’s drift, and might have left some time ago, had they not disliked seeming to desert under fire. Already some of the original abler members have drifted away or become inactive. This leaves the Society in the hands of the fanatic fringe of course…”

AND

Kirk discussed the views expressed in the JBS magazine (American Opinion):

“Nothing could do more to discredit all conservatives than the violent language and unreal views regularly found in American Opinion. As several conservatively-inclined gentlemen have remarked to me…they would be sorely tempted to believe that the leaders of the Birch Society are agents of the Kremlin subtly working to discredit all opposition to Communism by reducing anti-Communism to absurdity. All Americans of a conservative bent should be warned against associating themselves with an organization which is totally ineffectual in resisting Communism and socialism…”

Kirk’s comment was not hyperbole. Hundreds of Americans wrote letters to the FBI to inquire if the JBS might be a Communist-front group whose purpose was to discredit American leaders and institutions and cause internal dissension.

Eventually, former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover grew so weary of the falsehoods and hysteria promoted by Robert Welch and the JBS that Hoover made a public statement in November 1964 press conference. He observed that:

“Personally, I have little respect for the head of the John Birch Society since he linked the names of former President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the late John Foster Dulles, and former CIA Director Allen Dulles with communism.”

Hoover also testified before the Warren Commission that he considered the extreme right to be “just as much a danger” as the extreme left — and he then described arguments associated with the JBS as examples of extreme right views. In addition, the JBS and its surrogates around the United States lost libel lawsuits because of their reliance upon JBS propaganda.

nyscof • Feb 17, 2021 at 4:02 pm

There’s no conspiracy. Just a public health blunder. Fluoridation began in the 1940’s with the mistaken theory that ingested fluoride was essential to grow decay-free teeth. Modern science disproved all that. Ingested fluoride, neither a nutrient nor essential, doesn’t reduce tooth decay. Consuming a fluoride-free diet doesn’t cause cavities.

Fluoride is a drug and like all drugs has adverse side effects which affects different people in different ways http://FluorideDangers.Blogspot.com

Politics, not science, keeps fluoridation afloat

Thomas Tren • Feb 17, 2021 at 1:24 pm

This might actually be the dumbest thing I’ve ever read in my life. I want my 5 minutes back!

So many factual errors I lost count.

The John Birch Society has been right for 62 years (including when it exposed QAnon) and QAnon is a psyop.

Shame on the people responsible for publishing this drivel.

Noah Edelson • Mar 24, 2023 at 9:40 pm

TBS members like Edwin Walker were involved in JFK’s killing. McCain explicitly approved of it while on campaign saying “the intervention in Dallas.. I mean great tragedy”

Russia is now a capitalist corrupt constitutional democratic republic with the same 3 branches of gov’t as us. What is sad is we keep borrowing money from semi-Commie China to fight them.