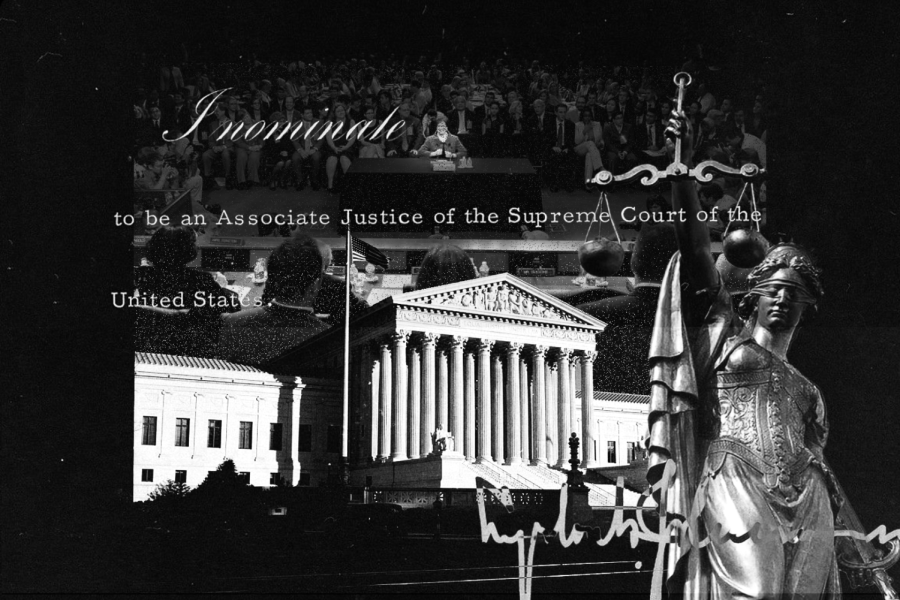

Rams Discuss: Ketanji Brown Jackson’s Supreme Court Nomination Hearing

Fordham students share their thoughts on the legacy of nomination hearings and the importance of having more public defenders on the bench

April 12, 2022

Two weeks ago, the Senate held a four-day confirmation hearing for U.S. Supreme Court nominee Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson. If confirmed, Jackson will be the first Black woman and third Black justice to serve on the Court.

Jackson was presented with offensive and irrelevant questions throughout the hearing in the Senate’s most recent embarrassing installment of political theater. Key moments from the hearing include Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) asking Jackson to define the word “woman,” Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) asking the justice to rate how religious she is, and Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) reading from a children’s book and asking Jackson if she thinks babies are racist.

Some political commentators expressed disappointment in the hearing and stated that Black women often face the unprofessional and demeaning behavior used by white senators in Jackson’s hearing. Jackson was repeatedly questioned on her qualifications as a judge and was asked questions about critical race theory, gender and white privilege, all irrelevant to the work she would do if approved to serve on the Supreme Court.

The double standard on what is considered acceptable behavior depending on a nominee’s identity maintains a barrier to who can be nominated to the Court.

Many applauded Jackson’s ability to answer questions in a calm and professional manner despite being persistently badgered by some senators. However, as others pointed out, Jackson’s gracious demeanor in the face of harassment was, unfortunately, necessary, as Black women are often held to a higher standard than their white or male counterparts.

Though Jackson was persistently scrutinized during her confirmation hearings, any annoyed reaction could risk her being labeled as unfit for the Court, a consequence stemming from biased judgments based on her race and gender. The double standard on what is considered acceptable behavior depending on a nominee’s identity maintains a barrier to who can be nominated to the Court.

Jackson is not the first marginalized Supreme Court nominee to face discrimination during her confirmation hearing based on her race and gender. In fact, Supreme Court confirmation hearings were created to do just that. At America’s founding, the president would nominate a Supreme Court justice, and the Senate would simply vote “yay” or “nay” on each nominee without holding a hearing to discuss the nominee. This process was often described as a “formality,” and nominees were often approved without controversy.

Senators who ask nominees questions such as if they think babies are racist make a mockery of this institution.

That changed when President Woodrow Wilson nominated Justice Louis Brandeis for the Supreme Court in 1916. Brandeis was the first Jewish judge to be nominated to the court, and until then, the vast majority of justices were white, Protestant men. The Senate held their first-ever confirmation hearing for Brandeis, which was seeped in antisemitism. It took Brandeis, who wasn’t even present at his hearings, a record four months to be confirmed by the Senate.

In the years since Brandeis’ confirmation hearing, other justices, notably Justice Thurgood Marshall, have continued to be harassed based on their identities through this process. This demonstrates that confirmation hearings have historically been used to keep certain communities from advancing to the nation’s highest court.

Supreme Court confirmation hearings have also been criticized for senators’ laughable and flagrant attempts to pursue political agendas and block Supreme Court nominees solely based on the party of the president who nominated them.

Supreme Court justices are not meant to be political representatives, but rather judicial experts whose job is to issue decisions on complex legal principles based on precedents set by the Court. Justices are not meant to answer to public opinion or issue decisions based on any political agendas, as the issues they decide are oftentimes far more complex and long-lasting than any current political issue.

For this reason, justices are appointed by presidents and confirmed by the Senate — not elected by the people. They serve lifetime appointments so they are not pressured to appeal to the public in order to keep their positions. Supreme Court justices should examine each issue in an impartial and nonpolitical manner; however, justices are often questioned on political issues at their confirmation hearings that have nothing to do with their prospective position on the court.

Confirmation hearings send the message that Supreme Court appointments should be politically motivated, but the Constitution and the precedent set by the Court in the early days of the U.S. discourage a political mindset on the bench. Senators who ask nominees questions such as if they think babies are racist make a mockery of this institution.

The current nomination system is, at best, inefficient and, at worst, an exclusionary tradition that could completely change the function of the Court as we know it.

Even after the introduction of confirmation hearings, many Supreme Court nominees were overwhelmingly confirmed by the Senate regardless of which president nominated them to the Court. However, as the country has become more polarized, so has the confirmation process.

For example, both Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Elena Kagan were nominated by Democratic presidents and had left-leaning views, but Ginsburg was confirmed by a margin of 96-3, whereas Kagan, 17 years later, was only confirmed by a margin of 63-37. Many claim this discrepancy is due to polarization and the Senate’s attempt to control the political leaning of the court.

In bringing politics into the formation of the Court, we risk losing the integrity of this institution and reducing it to nothing more than another political body whose whim changes as quickly as public opinion.

Senators pretend to understand the complexities of constitutional law and ensure that Supreme Court nominees are qualified for their position when, in reality, they are often trying to prevent marginalized voices from entering the Court and soft launching their latest political agenda. Considering this, it is worth questioning whether or not confirmation hearings are the best way to put justices on the Court.

While confirmation hearings can, in theory, prevent extremists and unfit candidates from sitting on the bench (such as Supreme Court Nominee Judge Robert Bork in 1987), it is worth questioning whether or not there is a more efficient way to confirm Supreme Court nominees without perpetuating discriminatory practices and undermining the legitimacy of the Court.

The current nomination system is, at best, inefficient and, at worst, an exclusionary tradition that could completely change the function of the Court as we know it. Whether we proceed by changing our standards at confirmation hearings or finding a different way to ensure that nominees are a good fit for the Court, we must at the very least encourage Senators to challenge exclusionary beliefs that are ingrained in our political system and to preserve the integrity of our institutions.

This is, of course, easier said than done, but our current system is not working. The only way to save the Court from being another government institution dominated by the changing political will of white men is to adapt the way that we approach forming it and encourage our politicians to hold our institutions accountable. Otherwise, we will be left with nothing more than an empty shell of what the Court was intended to be.