The Populist Persuasion: Talking Action Through the Americanism Credo

Populism empowers the people to hold the elite class accountable

Populism calls upon the disregarded masses to stand and fight for their worth by restoring the founders’ vision of our institutions.

December 27, 2021

Change is a disruptive force requiring the metaphorical wrecking ball. Questioning the establishment, the managerial elite, is absolutely necessary to keep powers in check and those operating accountable. It is only through the vigor of populism that America can utilize fuller political participation and awareness.

Populism in the U.S. echoes back to 1892 but is now a significant part of modern politics. It does not adhere to a specific set of values, although it tends to manifest on the right. Populism, the rhetoric of “the people,” calls upon the disregarded masses to stand and fight for their worth by restoring the Founders’ vision of our institutions.

Political communications professor at the College of Charleston Michael J. Lee presents a provocative interpretation of populism through his essay “The Populist Chameleon.” His stance is contemptuous of populism while acknowledging the incredible power behind it.

The paradox of populism lies in its restorative thinking of an idealized history.

“Simply put there is constantly a war going on between the two parties for the populist vote,” according to the late Republican strategist Lee Atwater. Where does this populist vote manifest in this tug-of-war? Atwater believes it to be exclusively liberal or conservative, but also contextually based, making it rather hard to truly define.

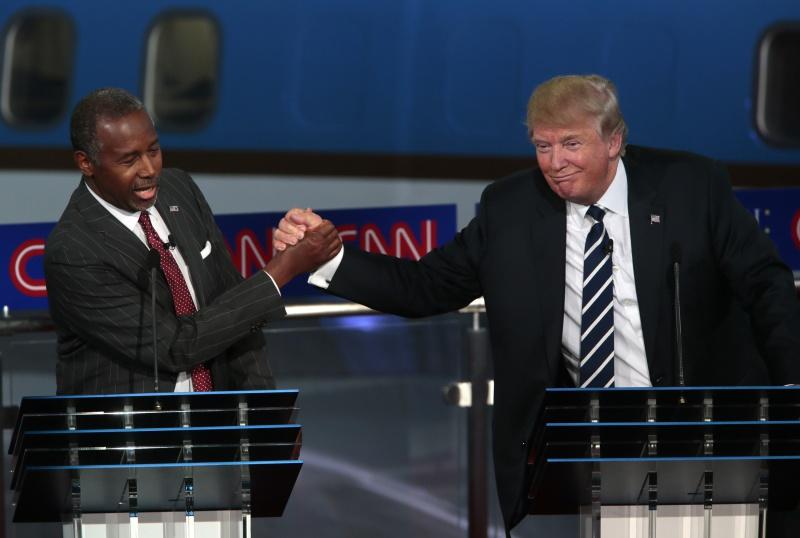

Historian and Georgetown professor Michael Kazin refers to populism as “a language whose speakers conceive of ordinary people as a noble assemblage not bounded narrowly by class; view their elite opponents as self-serving and undemocratic; and seek to mobilise the former against the latter.” Kazin’s interpretation sounds very familiar to the ideals of the 2016 platforms of Sen. Bernie Sanders and former President Donald J. Trump.

At the core of populism lies the virtue of the Founders’ vision with a heavy distrust of its current form. The paradox of populism lies in its restorative thinking of an idealized history. Trump’s slogan alone, “Make America Great Again,” demonstrates the aforementioned concept.

This American identity is but one facet of the populist demand — second to the revitalization of our institutions.

The trouble with this restorative logic is the narrowcasting of an ideal time. The 1950s may have been good for some, but certainly not for all, as Jim Crow was still alive and present. However, there is something to be said of those values emblematic of that era — almost as if they are central to the American identity. Religious faith, family and patriotism were at the forefront.

The 1950s postwar boom granted the “Golden Age of American Capitalism” and a thriving, middle-class with a suburban boom. Hollywood depicted wholesome traditional ideals through sitcoms like “Leave It To Beaver,” “The Honeymooners” and “I Love Lucy.” Actors such as John Wayne, Marlon Brando and Marilyn Monroe were hailed as pop-culture gods. Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Sam Cooke, among many, paved the way for the “American brand” of music. This American identity is but one facet of the populist demand — second to the revitalization of our institutions.

In “The Populist Chameleon,” political organizer and writer Harry Boyte viewed populism as “the conviction that an elite has dishonored a historically, culturally, or geographically constituted people, its memories, origins, common territory, ways of life.” Atwater and Boyte believe populism is more of a right-wing occurrence, which seems accurate as members tend to be in the majoritarian culture, unlike manifestations on the left, who tend to be reflective of the minority. Boyte’s acknowledgment of culture and history scripts Trump’s 2016 slogan accurately. Conservative America desires its preservation and respect for its heritage.

The groups that adhere to populism may be more important than the values themselves. “The people” provide the collective power. These groups are the ordinary, hard-working, common folk pitted against a common enemy that is economically and culturally distant.

The enemy is to be “big” in nature, akin to words like the “system” and the “establishment,” reflecting an impurity of the Founders’ conception. Idyllic demands result in political language of the non-negotiable or compromise. “Drain the swamp,” a popular metaphor of modern conservatives, is indicative of this mindset. Fundamentalist logic can garner support among the more passionate and even dissident, allowing unsung voices and ideas to be heard.

At another angle, Atwater sees populism as a narrative of victimization and redemption. The sacred people, betrayed by their own, seek redemption for their nation through a moral purging of governance. Populism, here, sounds more apocalyptic, although the general idea appears to be exemplified by the modern right. Trump’s populism viewed institutions, including the government, as morally bankrupt and deviating from the ideals of America. In contrast, left-wing populism focuses on corporate wealth, the billionaire class and the inherent horrors of capitalism onto its disenfranchised class of Americans.

Both sides of the political spectrum adhere to a common enemy — the elite.

Populists pit their audience, the “us” group, against a relatively abstract “other” group.

The Foreign Policy Research Institute analyzed quotes from both Sanders and Trump to demonstrate perceived populist rhetoric. Populists pit their audience, the “us” group, against a relatively abstract “other” group. Then, they press on “popular demands” which are general mantras on policy issues.

Sanders was quoted: “I don’t believe in special treatment for the top one percent, but I do believe in equal treatment for African Americans who are right to proclaim the moral principle that black lives matter.” In this statement, Sanders forms a divide through the special treatment of the wealthy and unequal treatment of the Black community providing an “us” group based on economics and race while signifying a popular demand.

Trump was quoted: “Under Hillary Clinton, it’s the powerful protecting the powerful. Politicians defending politicians. Insiders fighting for insiders. I am fighting for you. The government will work for citizens once again. The era of division will be replaced with a future of unity.” Trump presses on a broken system brokered by the powerful elite class, strengthening the “us” group against a corrupt government.

The language of populism is disparaging politics against a concentrated power between the citizens and what is said to be the “elite ruling class.”

Both quotes from each politician consider “the people,” as well as the proclaimed enemy and their desired pursuit — an idealized democracy. Both also share the same enemy, “the system,” but in different lights.

The language of populism is disparaging politics against a concentrated power between the citizens and what is said to be the “elite ruling class.” Populists frame “the people” against elites while providing a wealth of power through moral necessity, patriotism and the fear of a nation on the brink of ruin.

In the end, populists do not wish to dismantle the existing system — they wish to fix it through the restoration or purification of our institutions. Retaining our history and culture should not be a left or right issue, but it is the populists that fervently defend its preservation and respect.