NYC Board of Health Declares Racism a Public Health Crisis

Public health officials are increasingly acknowledging the health disparities exacerbated by racism

November 19, 2021

The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC Health Department) passed a major resolution on Oct. 18 declaring racism to be a public health crisis. According to the NYC Health Department’s resolution — which was signed under the department’s Board of Health (BOH) — COVID-19’s disproportionately high mortality rate for non-whites is a result of “extensively documented racial inequities” stemming from structural racism. To address the health effects of racial discrimination, the health department plans to allocate resources to “address structural racism and longstanding inequities.”

Government and civic institutions such as health care and hospitals have long been documented as having entrenched biases against non-whites. These disparities were — and continue to be — influenced by environmental pressures coupled with socioeconomic inequality as a result of centuries of white supremacist policies and attitudes.

However, the belief persists among health care providers that race determines health outcomes, with whites historically being seen as “healthier” than their non-white counterparts, particularly Black Americans.

Medical Racism: A Brief History

The causes of racism in public health are highly nuanced, but can all be traced back to racial discrimination and neglect by the medical community and government administrations.

Unethical experiments have been conducted on Black populations.

The detrimental effects of racism on mental health have been well-documented, with non-whites experiencing excessive stress as a result of discriminative policies and the legacy of white supremacy in America. The medical field has had a troubled history of mistreating and underserving non-white communities.

Unethical experiments have been conducted on Black populations, like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. In 1932, hundreds of Black men were infected with syphilis without their consent to study its long-term effects and transmission rate. Researchers also failed to provide the readily available penicillin cure for syphilis to any of them after the study’s conclusion.

The legacies of such injustices continue to stir distrust of medical services among Black communities, as evidenced by their reluctance to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. People of color also tend to have less access to affordable health care and fewer treatment options than their white counterparts.

Medical racism also affects mental well-being. Many people of color experience the pressure to code-switch, or act and speak more like white Americans, particularly in white-dominated settings. Such pressures stem from cultural norms that historically value “standard” English over African American Vernacular English in both casual and professional conversation.

Jeffrey Ng, director of Counseling and Psychological Services, said that “racism and other manifestations of systemic oppression have been public health crises long before any formal resolutions.”

New York City provides disparate medical care to its diverse residents, as demonstrated by a 2004 report from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The report found that communities of color are disproportionately concentrated in lower-income neighborhoods, have shorter life expectancies than white communities and are three times more likely to suffer from diabetes.

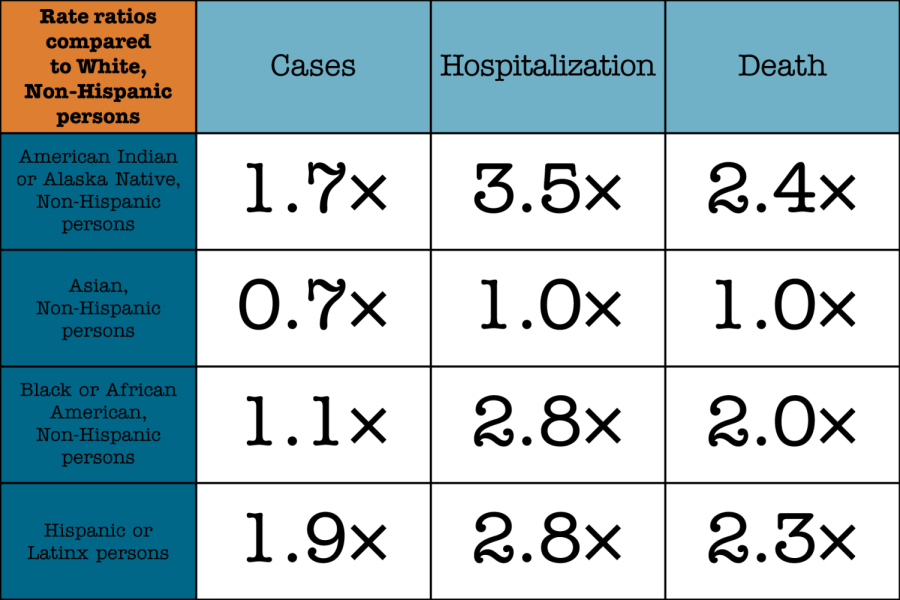

The COVID-19 pandemic has similarly underlined existing racial inequities, as seen by the higher rate of hospitalization and death among Black Americans compared to other racial and ethnic groups.

Combating the Health Crisis

The BOH’s resolution included various proposals and strategies to ensure “a racially just recovery from COVID-19 and other actions.” Such actions include allocating more funds and resources to health care for communities of color, as well as including race and ethnicity in future reports. The BOH additionally called for a review of the department’s “historic role in divesting and underinvesting in critical community-led health programs” for non-white communities.

The legacies of institutional racism continue to disproportionately affect communities of color citywide.

For students suffering from mental strain stemming from race, Ng recommended counseling services.

“We approach counseling/therapy for students who have experienced racism and/or other forms of identity based injustices from a trauma informed perspective, which all of our staff are trained in,” Ng said, citing mental health resources both on- and off-campus.

Beyond the BOH’s resolution, the legacies of institutional racism continue to disproportionately affect communities of color citywide. City leaders like mayor-elect Eric Adams are increasingly acknowledging how historical legacies of racism continue to afflict communities of color.

The BOH’s resolution emphasizes that the impact of racism on the health care of non-white populations cannot be ignored. While non-white communites continue to be plagued by insufficient treatment compared to their white counterparts, attempts like that of the NYC Health Department show that efforts are being made to change the structures of the city’s health care system.

New York City is not the first to pass a resolution on racism as a public health crisis. Milwaukee County in Wisconsin passed a similar resolution back in May of 2019 before the onset of COVID-19. Other townships and cities across the country released their own resolutions identifying racism as a health crisis. Many of these resolutions, including New York City’s, have been criticized for offering only suggestions on combating the crisis rather than concrete action to mitigate health disparities. How these resolutions will translate into real change remains to be seen.

Mauro • Nov 20, 2021 at 9:16 am

Pretty stupid assessment.