The Fall of Asia’s World City

I witnessed the battle for Hong Kong’s autonomy. Now, a year and a half later, I worry that Hong Kong has lost its war.

With the passage of China’s national security legislation, pro-democracy protesters can be arrested for a strict and wide array of actions the government sees as subversive.

March 5, 2021

It is rare to see a giant player in international trade and culture so forcefully stripped of its autonomy in just a few years, yet that is exactly what is happening in Hong Kong, formerly known as Asia’s World City.

It is rare to see a giant player in international trade and culture so forcefully stripped of its autonomy in just a few years, yet that is exactly what is happening in Hong Kong, formerly known as Asia’s World City.

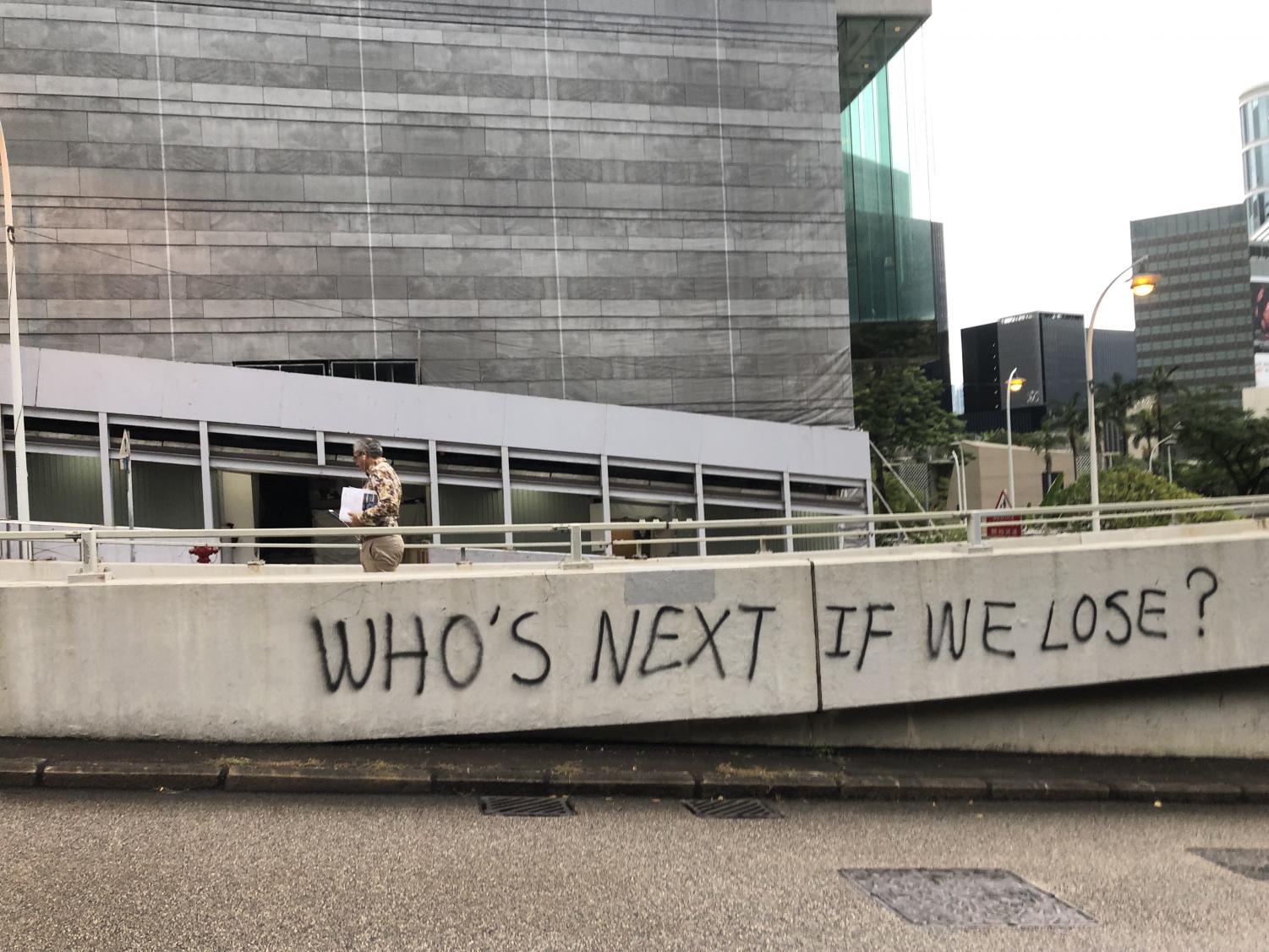

After months of protests, political resistance reached a peak in November 2019 when Hong Kong’s universities became battlegrounds for an epic showdown between pro-democracy protesters and police. Fires burned and tear gas permeated the city for days on end until the last remaining protesters were captured and arrested. Images of fire, youth in makeshift armor, horrific injuries and police brutality shocked international onlookers while China stayed ominously silent. The pro-democracy movement was a force to be reckoned with.

But in 2020 and 2021, out of view of the global community, Hong Kong’s resistance has been slowly snuffed out through the use of new legislation from Beijing. Escalating anti-democratic measures seem to be signaling the end for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement.

The National Security Law

China’s interference in Hong Kong’s affairs became inevitable as the Chinese government witnessed the escalation and sustainability of the pro-democracy movement, likely with heightened apprehension that the movement would spread into the mainland’s borders.

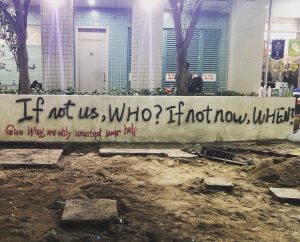

After all, Hong Kongers have long been proponents of the values China seeks to control: free speech, free assembly and suffrage. Hong Kong’s fervor spreading to China would be a nightmare for the government. So the Chinese government waited, biding its time until the movement became old news.

Then COVID-19 hit, keeping protesters off the streets and away from each other, drawing global attention away from Hong Kong. As other countries grappled with the virus in the following months, China crafted its response to Hong Kong’s revolution. In June 2020, China’s National People’s Congress approved the fateful legislation capable of quashing Hong Kong’s resistance: the national security legislation.

One protester was arrested for violating the new law because they held a flag reading “Hong Kong Independence” like so many others had been doing for years.

Arrests on the basis of that law were made in Hong Kong the day after its approval.

The most concerning provision of this legislation is the establishment of Chinese intelligence agencies in Hong Kong, but other provisions include the surveillance of foreign news and organizations; harsh punishments for anything officials deem subversion, succession or collusion with foreign entities; and the provocation of hatred against the government. Some of these offenses can land a Hong Konger in prison for life.

The national security legislation criminalizes the actions millions of Hong Kongers have been taking since the beginning of the movement. One protester was arrested for violating the new law because they held a flag reading “Hong Kong Independence” like so many others had been doing for years. Even actions I took as a foreign exchange student simply documenting the protests likely could be seen as violating the new legislation. This is terrifying news for Hong Kong. It could end the entire protest movement.

Purging of Pro-Democracy Figures

Using the national security law, the Hong Kong and mainland Chinese governments have targeted key figures in the pro-democracy movement. Many Hong Kongers in the media sector, government and the public eye have been arrested since the law’s implementation.

Notable former Hong Kong lawmakers Eddie Chu, Claudia Mo and Leung Kwok-hung were all arrested because of the security law, as were famed activists Agnes Chow, Joshua Wong and pro-democracy business mogul Jimmy Lai. Lai is the founder of the Apple Daily, a newspaper that frequently publishes pro-democracy content. The Hong Kong government is sending the clear message that it’s illegal to hold pro-democracy views.

The national security law has also indirectly purged Hong Kong of its activists, causing prominent figures to flee the territory. One of the most famous leaders in Hong Kong’s fight for freedom is Nathan Law, who wisely relocated to the U.K. shortly after the law’s announcement. I have no doubt he, too, would be arrested if he had stayed. Some of my friends in Hong Kong tell me that they have considered moving for fear that they will be tied to protests and arrested one day. Yet they are torn: How can one leave their home behind?

Indoctrination of Students

The national security law is even infiltrating Hong Kong’s classrooms. Children will be taught about the law as early as primary school. It is mandatory that students be taught that police are good and, conversely, that protesters are bad. Students will learn what the law means, why it is important and what it means to break it.

Their revolutionaries are jailed, their teachers and parents are silenced, and their history books only show the story of Hong Kong as written by China.

No longer will Hong Kongers grow up admiring revolutionaries like my friends did. Today, Hong Kong’s children will learn in school to look up to the police. Their revolutionaries are jailed, their teachers and parents are silenced, and their history books only show the story of Hong Kong as written by China.

This is absolutely strategic; China has seen for years the power university students have in shaping history, and Chinese leaders aren’t taking any chances of further rebellion.

International Responses to the National Security Law

Most of the world has watched idly as Hong Kong loses its freedom.

Former U.S. President Donald Trump was quick to voice support for Hong Kong, creating hope for U.S. interference, but Trump’s words were nothing more than empty rhetoric. In the end, he used Hong Kong’s worsening situation to further his economic agenda through financial sanctions. This move was nothing more than another petty blow in the long-standing U.S.-China feud, leaving desperate Hong Kongers in the cold.

As long as there are still some journalists and a relatively free internet, the injustices will not be forgotten or ignored.

The U.K. has made moves to accept Hong Kong residents and offer them a path to full citizenship, which would be useful for pro-democracy advocates hoping to flee arrest. This aid makes sense since Hong Kong was a British colony before 1997, but even countries not affiliated with Hong Kong should be adopting measures to accept Hong Kongers as refugees.

The U.S. has toyed with the idea of offering safety to Hong Kongers, but nothing is set in stone. It seems for now that only countries with the strongest ties to Hong Kong, like the U.K. and Taiwan, will provide refuge.

Looking Ahead

When I left Hong Kong, I was almost certain its pro-democracy supporters would succeed in their mission, even if it took a while to accomplish. I worried about my friends, but I believed that justice must prevail; the will of the people I had stood alongside was so strong.

But the Hong Kong of today is different from the one I left in many ways. The national security legislation has truly changed the game; if the protests continue, they will have to take a different form. I still see small shows of solidarity and protest in the online community, though I know the stakes are much higher now. Those activists who have fled overseas still advocate for the pro-democracy cause. As long as there are still some journalists and a relatively free internet, the injustices will not be forgotten or ignored.

Though Hong Kong’s fate looks bleak, I know that the revolution must still live on in the minds of those who bled for it. I hesitate to make a prediction on where Asia’s World City will be in a year, or five. But I am willing to bet that the revolution is not totally defeated — just in hiding, biding its time until Hong Kongers can rise up against China again.

Steve • Mar 7, 2021 at 9:41 am

Thank you for this thoughtful, very well written appreciation of the current plight of Hongkongers. I taught at a HK university for 20 years and share your sorrow.