Professors Emphasize Political Education in the Classroom

Adding political education to the curricula and syllabi of classes is a valuable complement to personal research and social media, common ways in which students obtain their information.

October 28, 2020

A form of child abuse: This is how President Donald Trump referred to attempts to incorporate critical race theory into history classes. This September, he called a press conference where he declared that he would combat any attempts to diversify the history curriculum in schools. He pushed instead for a national commission supporting “patriotic” education that would teach America’s youth to “love America with all of their hearts and all of their souls.”

This comes at the same time that Americans’ support of the Black Live Matter (BLM) movement increased in a period of two weeks as much as it did over the span of two years. Important issues such as the unarmed killing of innocent Black people and a discussion of health care in light of COVID-19 have been brought to the forefront of everyone’s phone screens.

As these events have unfolded, there has been an increased need for information. In addition to classes, students have taken learning into their own hands. In an anonymous political survey of 211 Fordham students conducted by The Observer, an overwhelming 94.8% of students looked for more political information outside of the classroom.

I think that certain classes may have a hard time incorporating politics into their respective subjects. However, professors should be more supportive in the fact that this year affects everyone including their students. Not speaking out or making their students even more aware of racial injustice is ignorant. Jaisa Pinnock, FCLC ’22

Most of them turned to film/television (83.4%), books (79.9%) and YouTube videos (69.8%).

Jaaee Nadkarni, Fordham College Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’22, said that she has “noticed a heightened emphasis on race in the US and the Black Lives Matter movement when it comes to class readings and discussions. One of my professors gives us the chance to speak about whatever’s going on in the world and how we feel about it before she begins the zoom recording.”

Other students like Emaan Choudhry, FCLC ’22, echoed this sentiment. “Although I do get most of my political information from personal research, I’ve found that class discussions have made me more aware of the other side, I’ve found issues I’m really passionate about,” she said.

She added that even in non-politics classes, “professors have been emailing students additional informative articles and encouraging us to vote.”

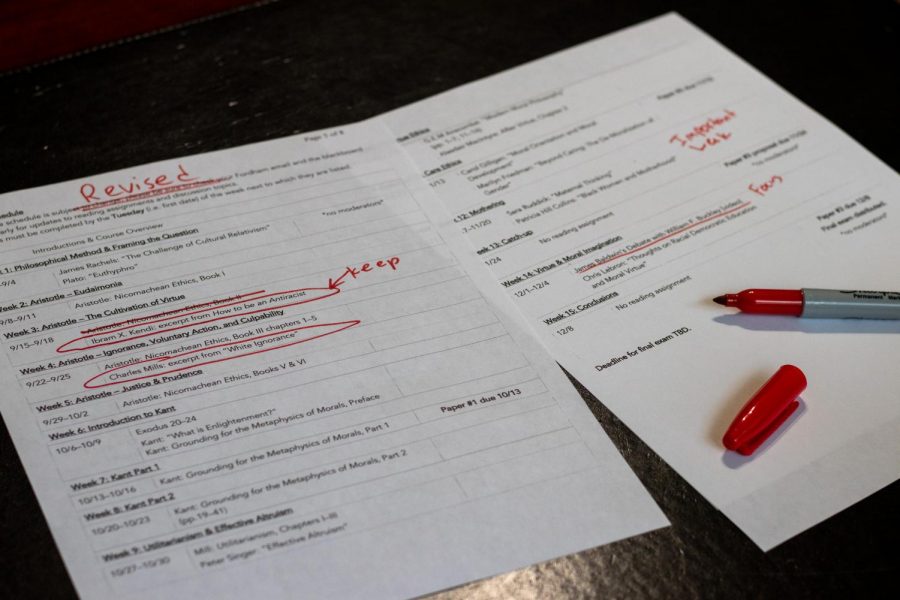

Professors are also doing their part to bring real-world events into the classroom. Professor Gloria Garcia, who teaches Introduction to Fashion and Culture, wrote, “Issues of racial injustice are so pervasive that they can be addressed almost through any subject of social study. This very course is by definition, a critique and a response to the Eurocentric view that fashion ‘started’ in Europe and developed with the emergence of capitalism.”

She went on to say that “After reading a couple of articles about these old tensions resurfacing among some young BLM organizers this past summer, I thought it was important to make room in the syllabus for these and other fashion/dress references appearing alongside the BLM movement in recent years.”

This shift in curricula was not consistent across all classes, however. Jaisa Pinnock, FCLC ’22, stated, “I do feel like there are a couple professors that have changed the curriculum but despite this change, there are very few who outright talk about what is going in the world during class.”

The need for political education in the classroom is not a new concept. During the Vietnam War, education on the conflict and the way the draft affected everyday Americans was notoriously amplified by college students on their campuses. Students were known for opposing the draft and bringing the issue to the forefront through demonstrations, protests and events.

This importance was noted by Garcia. “If I show a photograph depicting a Black female protester dressed in a summer dress standing in the middle of the street and looking in the eye of an agent in military uniform, students make the connection and understand the symbolic force of the state and its asymmetrical relationship to racialized bodies,” she said.

The lack of racially diverse educational opportunities pushes students to turn to social media. However, not everyone has social media. Those who do read a simplified version of an issue and assume their political education is done because to thrive on Instagram, an issue has to be reduced to a series of aesthetically pleasing slides.

In a New York Times article surveying high school students, one participant from Massachusetts said that “Students should be exposed to politics as much as possible in order to help them grow into active political participants. This understanding and early engagement can also help students to identify issues they care about, which is important for producing activists and national change.”

Some students have been going to protests and supplementing their knowledge with real world experience. Others are confined to their home by the pandemic and rely on their classes as the only exposure to people outside of their families.

Pinnock further added, “I think that certain classes may have a hard time incorporating politics into their respective subjects. However, professors should be more supportive in the fact that this year affects everyone including their students. Not speaking out or making their students even more aware of racial injustice is ignorant.”

Garcia echoed this, saying that professors should not just elect to alter their curriculum, but have a duty to do so. She summed it up by saying, “As an educator, my responsibility is to equip students with sound and ethical tools they can use, as independent thinkers, to make sense of their challenges and engage with the issues of our complex, connected realities.”