The Election, the Vaccine and the Fate of Higher Education

WHITE HOUSE VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The president receives a COVID-19 briefing in January. According to the New York Times, 12 possible vaccines are in the final efficacy trial phase, but after testing they will still need to go through the FDA approval process and be manufactured in large enough quantity before becoming available to the public.

October 28, 2020

According to Trump’s coronavirus response coordinator, Deborah Brix, a vaccine should reach college campuses as early as January 2021, which would usher in a more traditional spring semester. Brix’s timeline, however, may reflect Trump’s expectations rather than the actual state of COVID-19 vaccine research.

There are several phases in vaccine development, and scientists around the world are trying to compress these phases from several years into a matter of months; currently, the record for the shortest amount of time between vaccine discovery and approval is four years.

After scientists identify a vaccine candidate in the lab, it goes on to clinical testing in order to elucidate the vaccine’s safety and efficacy. This process comprises three phases: safety trials, expanded trials and efficacy trials. The vast majority of vaccines don’t make it all the way through these trials due to safety concerns or failure to demonstrate effectiveness.

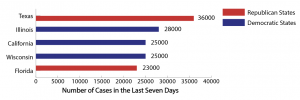

According to The New York Times Coronavirus Vaccine Tracker, 59 vaccines are in these clinical trials, with 12 of them in the final efficacy trial phase. United States pharmaceutical firms Moderna, Novavax and Pfizer all have vaccines in the final Phase 3 trial. Both AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson, other American companies developing vaccines, recently had to pause their Phase 3 trials due to adverse reactions arising among their volunteers, and it’s possible that other vaccine trials will follow suit.

However, the completion of the last phase of safety and efficacy testing does not mean that the vaccine will be immediately available to the American public. In addition to going through the Food and Drug Administration’s approval process, the vaccine needs to be manufactured in sufficient amounts to treat the entire population. Doses will most likely be limited initially, which will force health officials to determine who gets the vaccine first.

The next president of the United States will heavily influence these policy decisions. The president will directly or indirectly affect the selection of, distribution of and public confidence in the vaccine. This makes this upcoming election especially important for curbing COVID-19.

Trump’s ‘Operation Warp Speed’

Trump’s plan to roll out the vaccine, dubbed “Operation Warp Speed,” aims to roll out over 300 million doses to the American people by January 2021. The plan involves shrinking the span of development by running the phases of finding, testing and deploying the vaccine simultaneously. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Defense are in charge of distributing the vaccine.

In terms of cost to the consumer, the aim of Operation Warp Speed is to “provide free or low-cost” vaccines to the American public. The federal government has pre-purchased vaccine doses from several firms to fulfill this goal, and the HHS has affirmed that all of these taxpayer-purchased vaccines will come at no cost to Americans — who would qualify for these free vaccines remains unseen.

In addition to health care workers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published the COVID-19 Vaccination Program Interim Playbook of Jurisdiction Operations, identifies people attending colleges and universities as one of many critical populations that might be prioritized sooner rather than later.

Trump has voiced expectations that the vaccine might be ready to distribute as early as Nov. 3 — Election Day. Moncef Slaoui, Operation Warp Speed’s chief adviser, has talked down concerns about Trump’s eagerness to rush the vaccine trials: Slaoui told ABC News that he would resign if he felt undue pressure to accelerate the testing of the vaccines’ safety and efficacy.

On May 29, Trump announced his intention to relinquish ties to the World Health Organization (WHO), which would kill any American participation in the vaccine distribution on a global scale. Severing this tie also puts more pressure on the success of American vaccine trials: If a foreign vaccine trial is the first to succeed, then securing the vaccine for use in the United States might become a more cumbersome task without the aid of the WHO.

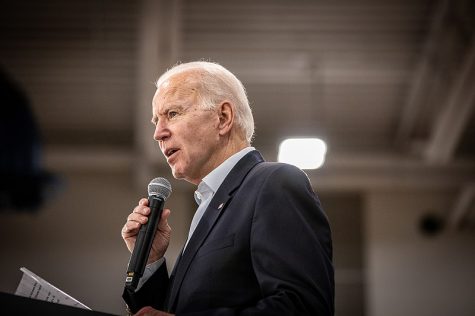

Biden’s Vaccine Plan

Biden’s plan is more global than Trump’s plan. One of Biden’s aims is to repair the United States’ relationship with the WHO in order to coordinate the international deployment of the vaccine.

Biden has also made a commitment to make the vaccine freely available to Americans, regardless of insurance status. More specifically, he calls for the federal government to purchase vaccines in order to make them available at no cost to “uninsured, underinsured or Medicaid-eligible” citizens.

In response to Trump’s comments on the vaccine being ready “within weeks,” Biden cautioned against this sentiment, stating that the vaccine might not be available until well into 2021. For this reason, Biden’s COVID-19 plan has included more testing, contact tracing and the supply of personal protective equipment in order to mitigate further spikes in cases.

Recent polls have indicated a pattern of vaccine hesitancy among college-aged Americans. One poll from Pew Research indicated that 31% of adults who are millennials or younger would probably or definitely accept the vaccine. Another poll found that a much larger margin of 18- to 29-year-olds would either not get vaccinated (35%) or were not sure (22%) — over half of college-aged respondents were vaccine-hesitant. Some of this skepticism can be attributed to Trump’s persistence in securing a vaccine in an unprecedented amount of time.

To instill more confidence in the vaccine among the American people, Biden has been preaching “science-based approaches” to combating COVID-19, and he has differentiated himself from Trump by committing to listening to vaccine experts and developers in order to ensure safety and efficacy.

A Vote for the Future

Unfortunately, neither candidate will hasten the discovery of a viable vaccine, nor will he procure a better vaccine, provided that medical researchers maintain control over the vaccine development process. The next president, however, can influence whether citizens would accept this vaccine and the science that backs it, as well as who has access.

As for colleges and universities, the return of in-person classes and on-campus events requires the certainty that those communal activities won’t further spread this virus. Therefore, the federal policies that affect distribution and selection of a vaccine candidate will, in turn, affect the pace at which students get closer to on-campus normalcy.