An Original Interpretation of Amy Coney Barrett

Why we and the Supreme Court should not look at America’s laws through ‘dead’ eyes

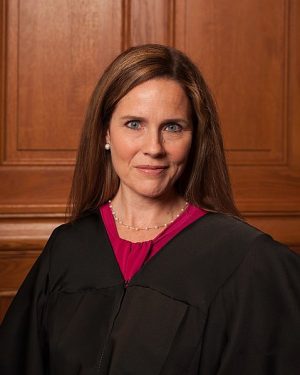

JAREK-TUSZYŃSKY VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett’s adherence to an originalist interpretation of the Constitution poses a threat to individual rights, environmental protections and the ability of the nation to grow and change.

October 18, 2020

Life or death, alive or dead: These phrases are commonly used in situations associated with issues of health, war or hyperbolized middle school drama, but many Americans don’t recognize that they also apply to the laws that govern our daily lives. One situation that is certainly on the scale of “life or death” is the judges’ interpretation of the Constitution and American laws.

With the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Sept. 9 and the subsequent nomination of Federal Appellate Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court on Sept. 26, the topic of Constitutional interpretation has become front-and-center in America.

Barrett views the Constitution and other laws as “dead” documents, meaning they should be understood according to the intentions of the original authors. She has maintained that she will “care about what people understood words to mean at the time that the law was enacted because those people had the authority to make law.” This view threatens the progress our democracy has made towards recognizing the rights of groups excluded in the initial drafting of our Constitution and foundational laws.

One crucial example is the right of women to have legal access to abortion, an issue defined by the historic case of Roe v. Wade and one whose future may depend on Barrett’s method of interpreting the Constitution.

Those who interpret the Constitution and laws as “dead” documents are referred to as originalists. Originalism is one method of analyzing laws that is often used in conjunction with textualism, or interpreting the law strictly according to the denoted meaning of the words on the page. Barrett is both an originalist and a textualist.

There is no reason to hold our current society to antiquated standards that were determined by a famously exclusionary group of white, wealthy men.

Nonoriginalists, or those who interpret the Constitution as a “living” document, use its framework to adapt the meaning of the law to fit with the values and goals of contemporary society. Originalists, however, believe that “the meaning of the constitutional text is fixed at the time of its ratification” and that “the historical meaning of the text ‘has legal significance and is authoritative in most circumstances.’”

The nonoriginalist method of interpreting the law is how we make progress; if we continued to interpret the law according to the original writers’ intentions, then women might be still largely confined to domestic duties and Black people might still be enslaved.

In a law review argument, Barrett defines originalists as conservative, in the sense that they are reluctant or resistant to change, and nonoriginalists as more progressive, in that they are responsive to “social justice” initiatives and “contemporary values.”

Catholicism and the Constitution

As students at a Jesuit institution, we are taught to fight for social justice and adopt contemporary values. Jesuits, an order within the Catholic Church, are generally more progressive than their fellow Catholic counterparts, who tend to be more traditional and conservative. But Fordham also recognizes its ties to the Church and dedicates “special attention to the study of the living tradition of Catholicism.”

Again, we see the juxtaposition of living and dead — except, in this case, it’s the interpretation of the Catholic faith. The living tradition of Catholicism, also referred to as the sacred Tradition, describes how Catholics make sense of biblical teachings in modern-day times.

Essentially, sacred Tradition encompasses not only the literal text of the Bible (Scripture) but also the traditions, teachings and writings of members of the faith that were incorporated into Church doctrine as the institution evolved; this is where the “living” part comes in.

As one Catholic priest popular on YouTube put it, “There are things, questions that you and I experience on a daily basis, … that the Bible never even imagined were going to be asked.”

While the Bible is used as the source of guiding principles, modern questions of interpretation are guided by an ever-growing body of knowledge on and about the Catholic faith.

Though Barrett has promised that her faith will not interfere with her legal decisions, her strong views and her actions taken to protest abortion raise questions about her ability to keep the two separate.

A similar argument can be made for how we should interpret the laws in America: We should rely on the Constitution and written laws to guide our principles but use the body of knowledge available to us beyond the words of the laws themselves, such as judicial precedents and court opinions, to interpret the law according to our modern context.

Even Thomas Jefferson argued in favor of a nonoriginalist interpretation of the new American laws.

He wrote that “No society can make a perpetual constitution, or even a perpetual law. The earth belongs always to the living generation … The constitution and the laws of their predecessors extinguished then in their natural course, with those who gave them being.”

Jefferson concluded that “If it (the Constitution) be enforced longer, it is an act of force, & not of right.”

It is clear that Jefferson thought a constant reevaluation of America’s guiding principles was necessary. He highlighted the underlying truth about laws: They must change with each generation, because every generation has new values, priorities and tools that previous generations couldn’t have possibly imagined, much less planned for.

A 2018 Pew Research Center poll found that contemporary Americans largely agree with this logic.

Therefore, the Constitution should be viewed as a living document interpreted in terms of the common law, or the law established by customs and judicial precedent, and the decisions made in previous cases upheld by a standard called stare decisis.

This approach allows for a current interpretation of the law, based in both past decisions and statutory law. It respects the law’s original goals but reinterprets them in the context of modern society, allowing for America to grow and change without constantly amending its written laws, a difficult task.

The United States Constitution was drafted with immense care, with the lofty ideals of freedom, equality and justice in mind. However, it was also drafted by slave-owning white men who failed to acknowledge or resolve a multitude of injustices within the emerging American society. Their bigotry inevitably left large swaths of the population without rights. We have made significant progress since the Constitution was written, but that progress would not have been possible without amending the Constitution and reinterpreting for whom exactly the framers intended their “Blessings of Liberty.”

Following this logic, there is no reason to hold our current society to antiquated standards that were determined by a famously exclusionary group of white, wealthy men. It has taken this country an astonishingly long time to recognize women as full members of society, but now that we’re here, it would be unjust to ignore that progress in favor of reading a document just because we have decided that its words can only exist in the context of the 18th century.

If we have accumulated knowledge over time which suggests that our governing principles do not serve all members of our current society, then the American people reserve the right to adjust them. Applying our experience would not be “destroying the systems that have governed us since 1789”; it would be part of the process of updating those systems to include members of the population who were intentionally left out.

Barrett Is a Barrier to Progress

Much of the progress the country has made in recent decades toward bringing justice to historically marginalized groups could be put in jeopardy by her arrival to the Supreme Court.

This brings us back to Amy Coney Barrett. Barrett’s commitment to originalist interpretation puts rights — like access to abortion, health care, LGBTQ+ rights, immigration, environmental protections and many more — at risk because she will likely overturn legal precedents.

In 2013, Barrett wrote, “I tend to agree with those who say that a justice’s duty is to the Constitution and that it is thus more legitimate for her to enforce her best understanding of the Constitution rather than a precedent she thinks clearly in conflict with it.”

Barrett upholds traditional values in both her practice of Catholicism and her interpretation of the Constitution, which means she also subscribes to traditional Catholic beliefs, such as the immorality of the practice of abortion. Barrett has clearly demonstrated her strong anti-abortion views and has a history of allowing her personal beliefs to influence her judicial decisions. Though Barrett has promised that her faith will not interfere with her legal decisions, her strong views and her actions taken to protest abortion raise questions about her ability to keep the two separate.

One of the cases with the highest risk of being revised, if not overturned entirely, is the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade decision to legalize and protect access to abortion. Over time, many other cases have been decided on the precedent set by Roe v. Wade, creating protections for many practices that we recognize as rights. But confirming Barrett as a Supreme Court justice would mean that there would be a majority of originalist judges on the Court, possibly leading to important precedents like the one set by Roe v. Wade being overturned.

The approaches our Supreme Court justices take to constitutional interpretation have a myriad of impacts on our lives. At the beginning of October, on the first day of the Court’s new term, Justices Alito and Thomas expressed concern that Obergefell v. Hobbes, the 2015 case that established the right to same-sex marriage, was not only unconstitutional but encroaching upon the right of Americans to exercise their religious freedoms.

Throughout his administration, and persisting through the pandemic, President Trump has prioritized the dismantling of the Affordable Care Act. A solidly conservative Court might be more likely to block broad legislative efforts to curtail environmental collapse. The outcomes of these and many other issues lie in the hands of the Supreme Court, highlighting the importance of understanding our judges and how they feel a document from two centuries ago should govern our society.

It is crucial that we acknowledge and prepare for the potential impacts of an Amy Coney Barrett confirmation on American society. Much of the progress the country has made in recent decades toward bringing justice to historically marginalized groups could be put in jeopardy by her arrival to the Supreme Court.