Why COVID-19 Continues to Devastate My RGV Community on the Border

While other states recovered, the Rio Grande Valley, or RGV, continued to struggle with COVID-19. Though the odds have always been stacked against us, we are determined to survive.

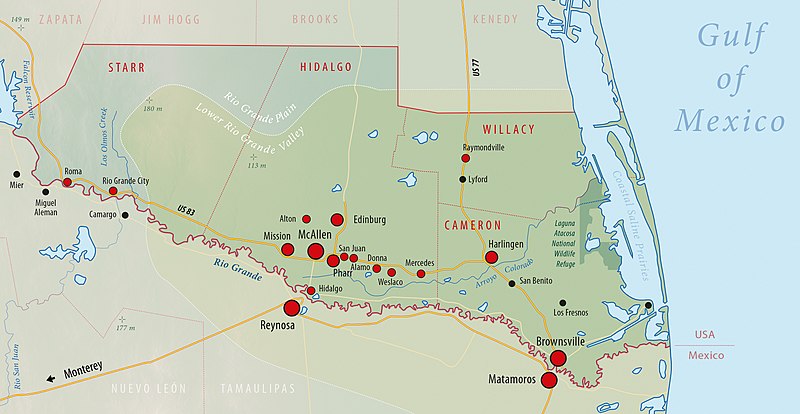

ZIETZ VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The Rio Grande Valley region has experienced a late climb in COVID-19 cases due to a lack of supplies and government support among other factors.

October 8, 2020

Licensed Vocational Nurse Martha Betancourt, a family friend, continued working during the earliest days of the pandemic despite being pregnant. She was committed to helping her patients.

When she tested positive for the coronavirus during mandatory testing at the nursing home where she worked, she had not been displaying any symptoms. But then her husband started running a high fever. The virus spread through their family like a wildfire. Soon Betancourt, her husband, her mother and her grandfather were all admitted to the hospital, each fighting for their lives.

The virus took three of the most important people in Betancourt’s life in just a few months. Only she and her unborn baby survived.

Betancourt’s heartbreaking story is only one of many in the Rio Grande Valley (RGV). The RGV is a region on the southernmost tip of Texas, on the border with Mexico. Its demographics reflect this, as 90% of the population is Hispanic or Latino, and 73% speak a language other than English at home. This mixture of Latino and American culture makes the RGV one of the most unique places in the U.S. It exists on the edge of two worlds.

Being a native of this region has played a huge role in forming my identity. The culture in the RGV is vibrant, and the people are hardworking, humble and community-oriented.

Unfortunately, it has historically been neglected by the state government, persecuted by federal government agencies like ICE and, more recently, subjugated to a tirade of racist and xenophobic verbal abuse from the current United States president. Politicians sworn to protect their constituents have abandoned them during the COVID-19 pandemic.

An Economically Strained Region

It took awhile for the virus to travel to the RGV. While New York was in its most desperate throes, there were hardly any cases here. But as time went on, the number of cases began to climb rapidly. Although New York quickly handled the virus and began seeing falling numbers as a result, the RGV’s response was much less efficient.

Nick Cañas, an RGV native and a student at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, recently lost his grandmother to COVID-19. He remembers ominously predicting the problems to come: “I knew the lack of supplies, support from the government, and our location meant we’d have the hardest time.” These are just a few of many factors that contributed to the loss of precious life in this border community.

The RGV is no stranger to hardship. In fact, the top five poorest counties in the state of Texas are all located in the RGV. The median household income in Starr County, which is in the RGV, is less than half of the state median income, and more than one in three residents live below the poverty line, according to a USA Today article published last year.

“I knew the lack of supplies, support from the government, and our location meant we’d have the hardest time.” Nick Cañas, RGV native

The economic situation of the region has many effects on the health care system as well as on individuals’ health within the population.

Nurse Ruby Cantu said that her hospital, Valley Baptist Medical Center, struggled to keep up as the number of critically ill patients increased at a shocking speed. She described the terror of her fellow nurses as they witnessed the exponential increase in cases.

“I could see the fear in their eyes. They were so scared, and I understood,” she said. Eight new COVID-19 units were operating at her hospital at one point, and many spaces were converted to accommodate the growth.

There was a shortage of personal protective equipment, a shortage of oxygen, a shortage of ventilators, a shortage of space and a shortage of staff. There were only 122 available Intensive Care Unit beds in the entire Rio Grande Valley, which was not enough for the population of 1.4 million.

Nurses who handled the explosion of the virus in New York came to the RGV in July, since it was now the place with a more dire need. While nearly every viral hotspot in the country experienced shortages of some kind, the RGV was particularly vulnerable because of the economic situation reflected in its health care system.

Many people here cannot afford to stay home from work. When Texas Gov. Greg Abbott prematurely eased business restrictions, RGV residents were faced with a perilous decision: Support their families or risk their lives. Losing their jobs was not an option.

Another grave systemic disadvantage of the region is its lack of health insurance. In the most populated counties, about one in four residents are without health insurance. Cantu believes that this reluctance to receive medical care has contributed to the number of fatalities: “They thought they could beat it at home … By the time they would come in they already had fluid in their lungs, and it’s too late.”

This statement hit very close to home. When my family was uninsured, there were many times when we hesitated to go to the doctor to avoid the costs, only waiting until our discomfort was unable to be ignored any longer.

Pre-existing Health Risks

Economic strain isn’t the only thing that has harmed RGV residents during the COVD-19 outbreak. Before the virus even came to the RGV, the region had high rates of health issues like heart disease, obesity and diabetes, which exacerbate the severity of the virus. Shockingly, one of the biggest cities in the region, McAllen, was found to have the highest percentage of obese adults in the entire country. It was also ranked third-highest in the country in percentage of diabetic adults.

Of course, things like obesity are mostly dictated by lifestyle and eating habits. But people with these problems aren’t entirely to blame — they simply don’t have access to healthy choices in food. The RGV is a food desert, which means that the entire region lacks healthy food options.

Before the virus even came to the RGV, the region had high rates of health issues like heart disease, obesity and diabetes, which exacerbate the severity of the virus.

Food deserts go hand-in-hand with poverty; have you ever seen a Whole Foods in a poor neighborhood?

There is not a single Whole Foods in the RGV, but there are plenty of cheap and unhealthy options for fast food and unhealthy grocery store products. Is a family trying to make ends meet going to spend $20 on one healthy meal, or are they going to spend the same price on microwave meals or processed food that can last the entire week? This is what happens in the Valley. As a result, people’s bodies were woefully unprepared to fight off the deadly virus.

Although our strong familial and community ties undeniably provide support during times of adversity, as the pandemic progressed, I realized that these ties were also working against us.

Disadvantages of a Close-Knit Culture

Latin American culture is extremely family-oriented. People gather in large groups for all kinds of occasions, whether they are large like a wedding or small like a weekly lunch. Tios, tias, primos and abuelos all attend, and it’s not uncommon to have friends of the family participate in family gatherings.

These traditions are extremely habitual and hard to break. In places like New York, however, people are more spread out; many people’s families don’t even live in the city, so gatherings of these types are less common.

The spread of the virus is not only the fault of nonessential ritual gatherings, however. COVID-19 spread quickly as a result of housing situations as well. Another facet of Latino culture in the RGV is shared responsibility for care of elders and children.

As people adjusted to the new normal of social distancing, the virus had already done its damage within individual households.

Many families have older relatives living under their roof and provide care for children of other family members. As people adjusted to the new normal of social distancing, the virus had already done its damage within individual households; for instance, a child being cared for by an aunt when their mother was working could contract the virus and spread it to elderly relatives and parents.

A situation like that is a result of multiple external factors: Because of economic strain, people must continue working and their children must be cared for by others who, as a result of Latin American culture, might also have extra family in their care. Next thing you know, entire families are infected as well as essential workers. This spread could be easily prevented by stay-at-home orders.

Solidarity Shines Through

Despite the unimaginable losses incurred by the RGV as a result of the pandemic, the strength of our people continues to shine through.

Nurses like Cantu have shown their resilience and infinite capacity for compassion even in the face of death. In some cases, nurses are the last people that patients come into contact with before they die, since family members can’t enter COVID-19 units.

Cantu remembers an encounter that will likely stay with her forever: “One patient carried a rosary with him the whole time. When it was time for him to go, I sat with him and prayed for him, and whispered that his family loved him … I knew they’d want that.” Her radical empathy comforted him until the end, even if his family couldn’t.

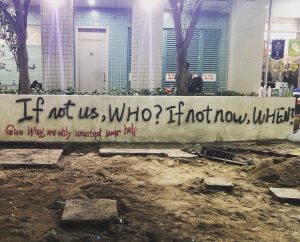

People have banded together to ensure that our region is cared for in this time of need, whether it be through crowdfunding, mutual aid, or small gestures of solidarity like distributing homemade masks.

After winning her battle with COVID-19, Betancourt gave birth to a healthy baby boy. Though her family was not there with her physically, she still feels like they are taking care of her. A GoFundMe Betancourt made to help cover the funeral costs of her husband, mother and grandfather quickly reached its goal with the support of the community.

She attributes this to her husband’s personality: He was always providing a helping hand to others, and now others are repaying the favor.

Stories like these show the soul of the RGV. Though the pandemic may have hit us harder than many parts of the country, and though we may have lost people we love, we stand tall. People have banded together to ensure that our region is cared for in this time of need, whether it be through crowdfunding, mutual aid, or small gestures of solidarity like distributing homemade masks. Our people are here for each other. Though the president berates us, the government oppresses us, and even though life is sometimes hard here, we stay because we love our community. We will come back from this pandemic stronger, smarter and even more connected than before.