A Look at Fordham’s Last Pandemic: The Swine Flu

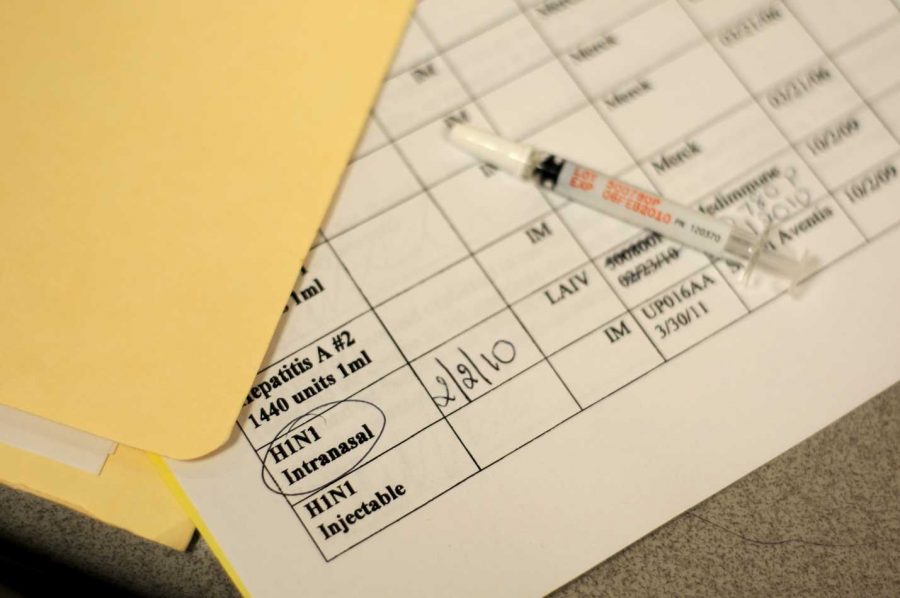

During the swine flu epidemic of 2009, University Health Services offered students vaccinations for the H1N1 virus.

April 22, 2020

“We hope that students who experience influenza-like symptoms or are diagnosed with the flu will take steps to isolate themselves to limit the exposure to others,” Dean Keith Eldredge said. This was not, in fact, in relation to the coronavirus crisis.

It was the fall semester of 2009, and a very different pandemic had reached Fordham’s doors: the swine flu. By December of that year, 165 cases of H1N1 had appeared at the Rose Hill campus and 12 at Lincoln Center.

While the coronavirus and H1N1 share symptoms such as fever, coughing and shortness of breath, they are very different from each other: The swine flu is 10 times less deadly than the coronavirus.

College students were considered particularly at risk for getting the swine flu due to their close physical contact in residence halls and social contact inside and outside the classroom. People between the ages of 18 and 25 were more likely to get the H1N1 virus itself, which many have attributed to lingering antibodies in people who lived through a swine flu epidemic in 1976.

Throughout 2009, Fordham took steps in line with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for institutions of higher learning to limit the spread of the virus. Fordham used many of the recommended precautionary and preventive measures, such as advertising information and advice about the swine flu. They also installed hand sanitizer stations throughout campus (some of which are still present today).

Another difference between the coronavirus and the swine flu was the university’s contingency plans, based on the CDC recommendations at the time. According to a September 2009 Observer interview with Eldredge, the university had no plans to shut down in the event of a widespread outbreak.

Instead, Eldredge said, “Self-isolation will be the first measure taken,” and that students who lived within a 150-mile radius of campus would be asked to return home if they contracted the swine flu, but that they would not be “forced to do so.”

For students who remained on campus, Eldredge explained that it would mean that “students living in three-bedroom, two-bathroom apartments will be asked to confine themselves to one room and one bathroom and separate themselves from their roommates.” If an outbreak at Fordham Lincoln Center became too large for just self-isolation, Pope Auditorium was to be used to house sick students because of its “good ventilation system.”

According to Eldredge, Fordham made plans to arrange for linens and food delivery in the event of quarantining students in McMahon Hall.

This was affirmed by the Rev. Robert R. Grimes, S.J., Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) dean emeritus, who, at a College Council meeting, said that “no plans have been made to close the college in the event of a widespread breakout.”

In October 2009, Marc Girard, FCLC ’10, was quarantined in an empty three-bedroom apartment on the 19th floor of McMahon after running a fever of 104 degrees.

He told The Observer in 2009 that “Everybody was great … they even brought me food from the cafeteria for the three days I was there.” Girard was released once he was fever-free for 24 hours. Other students with family nearby returned home to recover while they were ill.

While those in the Fordham community were concerned about the swine flu at the time, it ultimately had little impact on the Fordham community after reaching its peak in the fall semester of 2009.

Speaking to those on campus now, few memories of the swine flu epidemic remain. Aristotle Papanikolaou, a theology professor at Fordham and the Archbishop Demetrios chair in Orthodox Theology and Culture, wrote, “I do remember the epidemic, but, honestly, I don’t have any memories of Fordham doing anything out of the ordinary. None at all, in fact.”

Jason Morris, chair of the natural sciences department at FCLC, concurred, writing, “I don’t remember the event at all.”

Morris accounted for this gap due to the existence of a vaccine, saying that its presence “is probably a good bit of the difference between something I don’t even remember a decade later and something that will be a formative experience for several generations of people worldwide.”

Once a vaccine for the H1N1 virus was released, Fordham’s University Health Services provided a flu shot clinic in November, inoculating 600 students at the event. They continued to vaccinate students throughout the semester with remaining doses, despite some student reluctance.

Anna Loizeaux, FCLC ’10, told The Observer in 2009 that she did not receive the vaccine because “I feel like influenza is always changing, and a vaccine will only serve to make the virus stronger and our immunities to it lesser … How do we know that H1N1 won’t be different in a month?”

Sam Wong, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences ’11, said, “[I think] universal vaccination does not put an end to the viral infection. Students need to exercise proper hygiene and that should be good enough.”

Following the fall 2009 semester, fears about the H1N1 virus largely quieted and were eventually swept away as the epidemic died down.

While the coronavirus and swine flu pandemics received very different plans from Fordham, it is important to remember that the two diseases are markedly different from each other. The path of the university will remain unclear as the pandemic continues to unfold, as this virus is so different from the one that came to the university over 10 years ago.