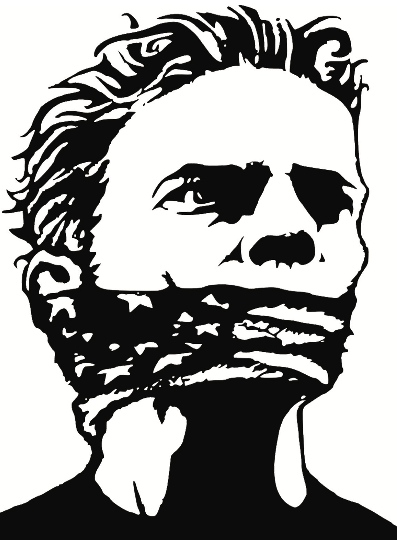

Free Speech Belongs on College Campuses

GRAPHIC ILLUSTRATION VIA PIXABAY

Free speech on college campuses is essential, and if done right, it’s easier than one might think.

December 5, 2018

As Americans, we are lucky to live in a country where we are able to freely speak our minds and let our voices be heard. These same rights extend to the thousands of colleges and universities across the nation. The unfortunate reality is that people take advantage of it and use their rights as Americans to spew hatred and evil, speaking in favor of evil as Richard Spencer did when he visited Michigan State University in March of this year.

This sadistic dialogue of blatant racism and violence gets misconstrued with that of regular political dialogue simply because people are led to believe that these hateful views are a political platform. Now that the two are meshed together without any merit, the United States has reached a breaking point on the free speech issue on college campuses.

Often at universities, members of college communities push to censor many ideas even if they do not resemble radical hatred. They sometimes even restrict simple political dialogue and confrontation of issues. In March, a Washington Post article found that 37 percent of college students found it acceptable to shut down events of speakers that visit campuses if they subjectively find what they are saying offensive or if they blatantly disagree with what the speaker has to say. On top of that, 10 percent found it was within limits to use violence to prevent speakers.

Ann Coulter was supposed to appear at a College Republicans event at Fordham in 2012 before her invitation was rescinded due to the backlash created in part due to Coulter’s past statements regarding her views. University President Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J., put out a statement shortly after the rescinded invitation, saying, “Her rhetoric is often hateful and needlessly provocative.” Now, as someone who isn’t a fan of Coulter at all, I disagree with the how McShane framed his argument against her speaking at Rose Hill. In many cases, her rhetoric is unproductive indeed. However, the structure of his argument is similar to that of someone who would want a speaking event shut down for the sake of disagreement on politics.

More prominent amongst millennials nationwide is Ben Shapiro. For years Shapiro has been touring college campuses across the nation, and at many of his lecture stops he has been called every -ist and -ism in the book. This is all despite the fact Shapiro always prioritizes speaking with those who disagree with him and has been the number one target of the alt-right because of his Orthodox Jewish faith as noted by the Anti-Defamation League. Previously, he visited UC Berkeley in 2017, and a riot squad gathered outside of the auditorium in which he was speaking. In response to those protesting him outside with the chants “No KKK, no racist USA,” Shapiro said, “I think it’s anyone perceived as a conservative by Antifa and radical left groups like that is immediately called a Nazi and a fascist.”

To combat this issue of barring different political speakers on campus, I would urge everyone to engage in respectful dialogues about the issues that are plaguing the United States. I recently had a great discussion with fellow staff writer Gabriel Samandi on “Retrospect,” The Observer podcast, and it was a refreshing dialogue because of its rarity. It is possible to sit in a room with someone you disagree with and discuss what the issues are and then walk out of that room as friends.

Politics have divided us because of the people who represent the ideologies. But if you take a look at the real people, not in Washington, but living a daily life like everyone else, you’ll find the compassion within them and how they see the world. Like myself, you might even make a friend out of disagreeing. This is how America was founded after all.

Free speech is a dicey issue; it can offend people, but multiple Supreme Court rulings have stated it is an American hallmark and our right. But schools that bring in conservative speakers are chastised and singled out for encouraging hate speech. In reality, this “hate speech” is that at all. People are too afraid of other ideas that might be different from their own. The very reason our families send us through college is to receive a well-rounded education that opens us up to new ideas to prepare us for the real world. If we don’t have a free exchange of ideas within our classrooms and auditoriums, there is no purpose in paying tens of thousands of dollars to be here.

John Harvey • Jul 14, 2020 at 6:55 pm

First, let me mention that Martin Speech’s response is truly garbage in that it is not even clear what his critique (if any) is.

But to the issue:

On the one hand, some readers will agree with me that denying conservatives permission to speak on a college campus by imposing huge security fees is disturbing.

On the other hand, if one puts oneself in the place of the relevant administration officials, one can see that the security budget is a legitimate concern. (I set aside the question of whether a certain set of administrators are primarily concerned with budget or whether they primarily want to prevent conservatives from speaking. It is the actions not the motives of the officials that may cripple freedom.)

I therefore propose a common sense solution, hoping that others with experience in relevant affairs (for example, those who have worked in campus security) might respond.

Let S be the total security budget for a campus’ fiscal year.

Let s be the amount that the responsible official estimates will be needed for tasks other than controlling crowds at speaking events.

Then S – s is what the administration can afford, from ordinary sources, to spend on security for these events.

Let the official make an estimate of how many speakers will accept invitations during the coming year from student groups. Call this p.

Let T be the amount of money that it is estimated will be needed for security at these events in to addition to S – s.

Then let each campus group that has invited a speaker pay a security fee of T/p for each speaking event.

In this way we can realistically take care of the security problem without punishing those with unpopular views.

Of course, these estimates, which can only be based on previous years’ experience, may turn out to be very rough, but organizations have to act on such estimates all the time — such as when they estimate how much funding a city’s police force will need during the coming year.

If the reader considers this proposal naïve, let him offer a better practical one.

Martin Speech • Dec 26, 2018 at 10:58 pm

Please stop writing, this is garbage. As is your website