DeVos’s New Title IX Proposal Is Fair for Everyone

December 5, 2018

After much anticipation, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos announced on Nov. 16 a sweeping proposal that would overhaul the way colleges and universities across the country handle cases of sexual misconduct. If implemented, these changes would reinstate basic due process and fairness within Title IX investigations.

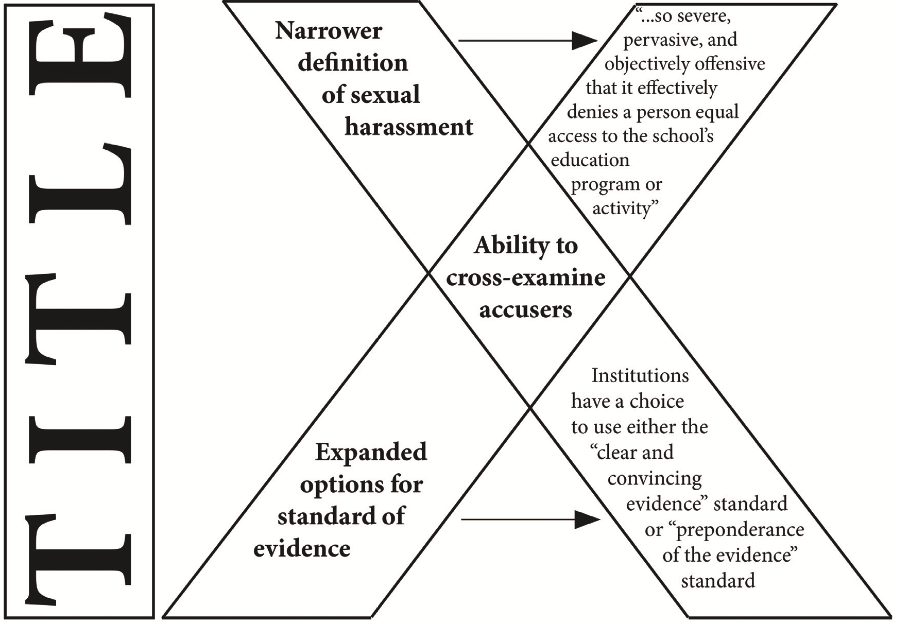

Perhaps the most important change gives students accused of sexual misconduct the opportunity to cross-examine their accusers, albeit through video calls out of respect for the trauma that assault survivors can face. Cross-examination is so fundamental to legal proceedings that it is astounding certain universities have expelled students without permitting the accused to question their accuser or any witnesses. The Supreme Court has called cross-examination the “greatest legal engine ever invented for discovery of the truth.” In criminal trials, courts allow all defendants, no matter how egregious the accusation, to cross-examine their accuser in court.

Additionally, the rules protect the First Amendment by tightening the definition of sexual misconduct, using direct language from the Supreme Court. As award-winning journalist Robby Soave stated, “Under the previous system, administrators were obliged to investigate any unwanted conduct of a sexual nature, which is a fairly wide swath of behavior. Some officials even interpreted this to include mundane speech that happened to involve gender or sex.”

Likewise, the proposals give universities the option to resolve their cases using either the standard of “the preponderance of evidence” or “clear and convincing evidence.” Previously, schools were forced to use the former, which meant they only needed to prove that there was a 51 percent likelihood an alleged incident took place. The latter mandates that the evidence is substantially more likely to be true than not. By utilizing the higher standard of “clear and convincing evidence,” DeVos rightfully raises the burden of proof in order to make investigations more closely resemble a true criminal trial.

For far too long, college kangaroo courts have gone virtually unchecked in labeling an accused student as guilty until proven innocent. Fordham University hosts a one-sided process for investigating sexual misconduct allegations. Fordham uses an extremely broad definition of sexual harassment, which includes behavior as nonchalant as sexually explicit jokes. It also does not allow cross-examination and has long employed the standard of “the preponderance of evidence.” Extremely unsettling, the answer to “Do I have to prove that I have been the victim of sexual assault, sexual violence, stalking, or domestic or dating violence?” in Fordham’s Sexual Misconduct FAQ is “No.”

Instead, the burden is placed on the Department of Public Safety. Not only does this process run antithetical to criminal trials, but even in civil cases resolved on the basis of “the preponderance of evidence,” the burden of proof is always placed on the plaintiff.

Now, you might wonder how frequently sexual assault and rape are falsely reported. The truth is that we don’t know. Frequently-cited studies place the rate of false reporting between 2 and 10 percent, but this doesn’t mean that 98 percent, or even 90 percent, are true. This number does not include cases where a court could not establish innocence or guilt. Most cases lie in a state of limbo where a jury has no idea what happened, especially in a “we had sex, but it was consensual” scenario.

The prevalence of sexual assaults on college campuses is not settled science, either. Democrats as high in rank as former President Barack Obama often cite the “one in five women are sexually assaulted in college” figure, although the study that resulted in this alarming number was conducted as an anonymous survey that polled women at only two U.S. colleges.

Aside from the survey not being representative of all U.S. college students, participants were asked ambiguous questions about events that may not even constitute sexual assault. For instance, it asked women about non-consensual events they “think (but are not certain) happened.” Despite inquiring of scenarios that constitute sexual assault, questions like this can make participants second-guess their own recollections of blurry events, such as a night that they were intoxicated.

Information from the Bureau of Justice Statistics paints a different picture of sexual assault at colleges. According to their nationwide data collected between 1995 and 2013, the rate of sexual victimization is 6.1 per 1000 students. This data also takes into account cases not reported to the police, which is significant considering 80 percent of students do not report their assaults to those authorities.

Despite these statistics, court reversals and even criticism from liberal icon Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the reaction from certain groups over this change has been astonishing. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a group ostensibly dedicated to upholding rights of the accused, tweeted this about the proposals after their release: “It promotes an unfair process, inappropriately favoring the accused and letting schools ignore their responsibility under Title IX to respond promptly and fairly to complaints of sexual violence.”

It promotes an unfair process, inappropriately favoring the accused and letting schools ignore their responsibility under Title IX to respond promptly and fairly to complaints of sexual violence.

— ACLU (@ACLU) November 16, 2018

“Inappropriately favoring the accused” is the jargon of judges who incarcerate people for possession of a gram of marijuana. Despite the ACLU’s claim, it is not mutually exclusive to defend due process and support survivors. Accusers will still be able to make their voices heard, ensure their safety during the investigation and even appeal the university’s decision (which is not offered in a criminal court).

It is hard to underestimate how important this regulatory change is. One sexual assault is too many; one rape is too many; one innocent person convicted is too many. These proposals are an excellent first step in returning normalcy and standard investigative procedures to college campuses.