Searching for Lesbian London

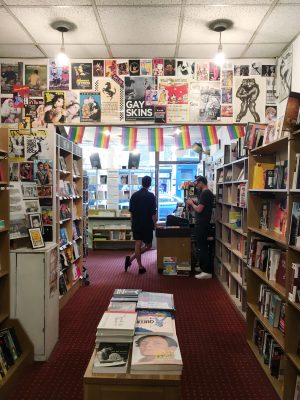

The vibrant interior of Gay’s the Word, London’s only LGBT bookstore. (NADINE SANTORO/ THE OBSERVER)

July 4, 2017

When I was 14, I realized (or rather, finally admitted to myself) that I liked girls. I came out as bisexual the following year, but it wasn’t until early March of this year that I came to terms with the fact that I’m a lesbian. After years of dating men and being loudly, proudly bisexual, this realization forced me to rethink everything I thought I knew about myself. It has been a confusing past four months, equally liberating and painful. At age 20, I’m entering my senior year of college, but in many ways I feel 14 again: lonely, grappling for language to describe my experiences, battling with internalized homophobia.

Being in community with other lesbians at school, especially my best friend Tina, has been immensely comforting, and I knew that coming to London to study abroad would mean losing that safety net. I wasn’t exactly terrified, but I was definitely uneasy. But hey, I thought, it’s June. It’s Pride month. I may be missing NYC Pride, but at least I’ll get to experience Pride in London, right?

Wrong. London’s pride parade takes place this year on July 8, the weekend after I fly home. Disappointed but not discouraged, I started researching LGBT London, hoping to find some hub of community. Pages deep into my Google search, I came up relatively empty-handed. My gay tourism agenda was comprised of just three things: visit Gay’s The Word, London’s only gay bookshop; check out the gay bars in Soho (like G-A-Y, Heaven, The Village and She); and see the Tate’s new Queer British Art exhibition.

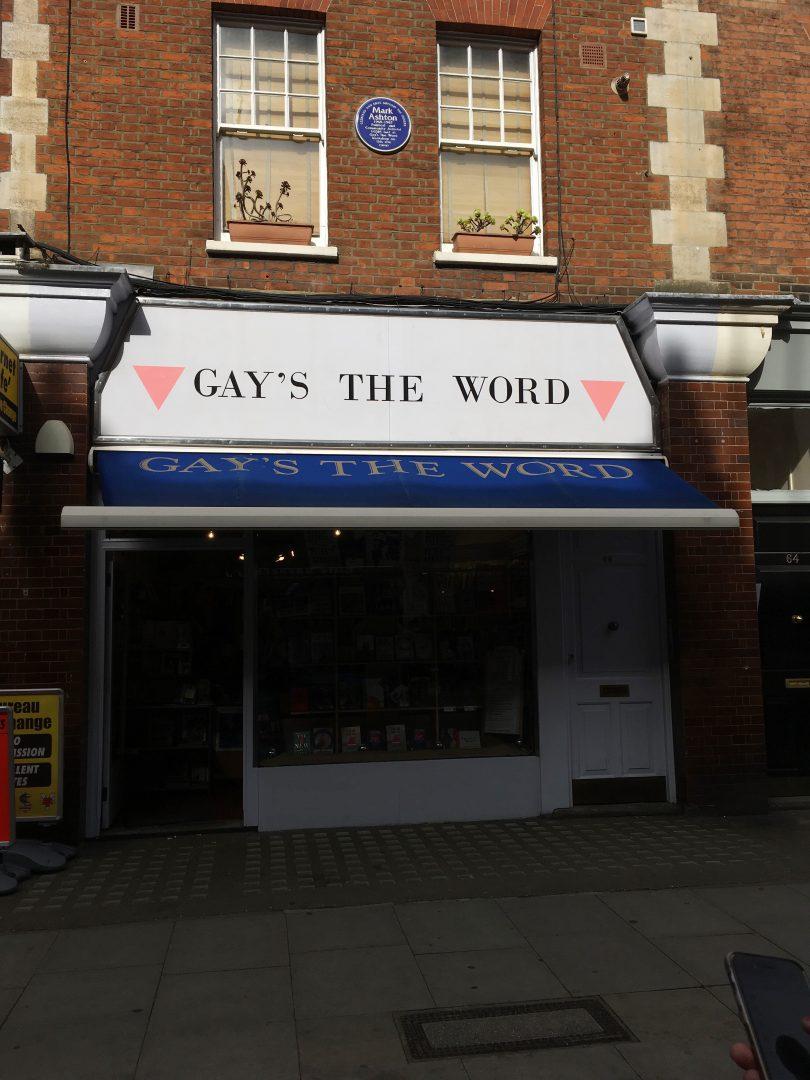

On my second Saturday in London, after much deliberation over our outfits (“Does this shirt make me look straight?”), my friend Callan and I hopped on the tube and headed towards central London. Our first stop was Gay’s The Word. The bookstore’s front is relatively plain and unassuming, so much so that we walked right past it at first, but the inside is an explosion of color. Rainbow flags hung from the ceiling, and joke books like “Is My Cat Gay?” shared a shelf with novels by James Baldwin and graphic memoirs by Alison Bechdel. Like many gay and lesbian bookstores in the United States, Gay’s The Word historically served as a community organizing and social space, but today it’s only a bookstore.

As afternoon turned to evening, Callan and I headed into the heart of Soho. We walked down Old Compton Street, the epicenter of gay nightlife in London. The sun had hardly set but pub-goers were already spilling out onto the street, laughing together over a pint. I spotted a few obviously gay couples amongst them, but Callan and I quickly realized that most of the gay nightlife takes place underground—literally. The entrance to She Soho, London’s only remaining lesbian bar, is just a sleek black door on the side of a building with a sign overhead. After the (female!) bouncer inspected our IDs and and handed us each a wristband, we descended a flight of stairs into the dimly-lit bar.

I was way out of my comfort zone. Neither of us had been to a gay bar before, and between the loud music, the strobe lights and the crowd of women, it was an incredibly overwhelming atmosphere. We bopped awkwardly in the corner of the room, sipping our drinks and nervously laughing. Probably taking pity on us, a girl finally approached and asked us to dance with her and her friends. Halfway through the first song, when I was finally starting to feel more comfortable, she leaned in and asked us, “So… why are you guys here?”

“Well, why would we go to a straight bar?” Callan asked.

The girl’s jaw dropped. “You’re gay?” She laughed. “No, no.”

“Yeah, we’re gay,” I said, my tone a little colder than I intended it to be.

“Well, I’m bi,” Callan admitted, almost apologetically.

The girl scoffed, waving her hand dismissively in Callan’s direction. “Oh, come on, get out,” she laughed, but it didn’t feel like a joke.

“Don’t be like that,” I protested, throwing an arm around Callan in a visible show of solidarity. The girl shrugged and turned back to her friends, and Callan and I drifted out to the edges of the crowd. We tried to stay for one more song, but our night had already ended the moment the girl questioned our right to be in that space. Dejected and confused, we made our way back to the tube. I replayed the interaction over and over, micro-analyzing our movements, outfits, and words, wondering why we didn’t seem “gay enough” to be there.

Growing desperate for an affirming community, I reached out to gay London locals the following week. While on a walking tour of the City of London with my class, I chatted with Sean Gallagher, a Fordham alum who has lived with his husband in London for many years.

“I didn’t want to tell you that there isn’t any [gay culture] but… there isn’t any,” he admitted. In many respects, he explained, gay people have assimilated into the heterosexual majority. At the cost of a coherent community, this ultimately seems to mean good things for the overall safety and happiness of LGBT people in London. “When you have the Tories backing gay marriage, you know you’ve hit that point,” he said with a shrug. “It’s becoming a non-issue.”

Kristina Gulbinaite, a 23-year-old who recently graduated from Middlesex University in London, had similar things to say about lesbian culture, or rather the lack thereof, when I spoke to her later that week. Originally from Lithuania, Gulbinaite stressed her relief and gratitude that London is a relatively safe city for LGBT people. “There’s probably no need to say that Lithuania is very homophobic country,” she said. “To be honest, during my first year of London, nothing much crossed my mind about the community. I was just amazed that I could hold hands and kiss a girl in public and I wouldn’t receive any negative comments.” She added, “When I moved to London, I felt like someone unchained me and I could breathe again.”

It occurred to me that maybe I was judging London too harshly on its lack of community, instead of focusing on the fact that it is a relatively safe place for LGBT people to be. Still, I couldn’t shake the feeling of isolation. I was frustrated that the only place to connect with other gay people seemed to be the bars, which are not only inaccessible to people of all ages, but aren’t particularly comfortable or welcoming environments for many members of the community. Kristina agreed that there wasn’t much outside the clubs—as an art student in a photography course, she met most of her LGBT friends by chance at university.

“Once my girlfriend said that she would love to go and meet some lesbians and just chat, have a cup of coffee with them, share one another’s experience,” she said. “And to be honest, I don’t really know of any lesbian communities where you could just meet people or get some support.” She mentioned that she had asked her friends if they knew of any community space that wasn’t centered around clubbing, but they all drew a blank. “If there is, then there isn’t enough of it.”

Hoping for a more inviting kind of community, I headed to the Queer British Art exhibit at the Tate Britain last Saturday by myself. After getting lost and caught in the rain without an umbrella, I arrived at the museum, damp and on-edge. My visit coincided with the kickoff of London’s Pride festival, so the inside of the Tate had been transformed temporarily into a nightclub—the DJ was blasting “Mamma Mia” and I had to push through a crowd of dancing bodies to reach the information desk and purchase my ticket, feeling vulnerable.

I presented my ticket to the butch woman working at the door of the exhibition, wondering if she recognized something in my eyes, wondering if she knew. She handed my ticket stub back to me and I pushed through the heavy double doors. When they swung shut behind me, a deafening quiet drowned out the music and the shouts from the crowd. The silence was crushing; alone in the large empty room, I felt fragile, exhausted, afraid. Watched only by the painted eyes of Sappho and her lover, I burst into tears.

I walked through the rooms, weeping quietly. I had expected to feel less out of place in an art exhibit than I did at the bar, but with every step I felt more and more isolated. Staring into the eyes of butch women in history felt like coming home, but the museum refused to label them as lesbians, opting for the more universal “queer.” It’s a word that used to resonate with me, but fails to describe the unique experience of being a woman exclusively attracted to and committed to women in a male-centered world. Emerging back into the party outside, my face stiff with dried tears, I found myself aching to return home to New York.

Maybe I felt the lack of community in London more deeply just because I’m at such a crucial juncture in settling into my own identity. Whatever the reason, the isolation I experienced here made me all the more grateful for the community I have waiting for me in the Bronx when I return home at the end of this week. Community isn’t just about social interaction and having fun with people who are like you—for many, LGBT community can be lifesaving. It can help people heal from the pain and trauma of homophobic abuse, and it can help to clarify identities and desires that would’ve taken much longer to sort out alone. As much as I’ve loved being in London, I can’t wait to hop off the plane and return to the support and the friendship of all the amazing women-loving-women in my life who have made it possible for me to find the courage to live openly as the person that I am.