Theater Review: “An Octoroon”

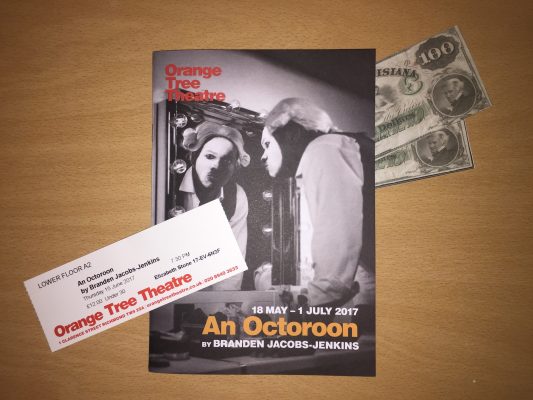

Professor Elizabeth Stone’s travel writing course attended a performance of An Octoroon on June 15. (IZZI DUPREY/THE OBSERVER)

July 4, 2017

Confetti, $100 bills, pieces of cotton and styrofoam balls drift through a pool of blood, and the room is silent. The expectant pause is broken by Alistair Toovey, in blackface, uttering: “The whole point of having this thing was to make you feel something.” It worked. For two and a half hours, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ play “An Octoroon” (a satirized adaptation of Dion Boucicault’s 1859 melodrama “The Octoroon,” in which the octoroon daughter of a plantation owner is sold as a slave after her father’s death) captivated that night’s audience of the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond. Jacobs-Jenkins, a 31-year-old playwright whose play “Gloria” was considered for a Pulitzer Prize and who was the recipient of the 2016 MacArthur Genius Grant, clearly admires Boucicault, having dedicated an abundant amount of time to researching his work. This show, however, exists to critique his original piece by recognizing the racism involved.

Ned Bennett’s direction is new, inventive and exciting. Having previously directed “Pomona,” a bold and dark drama, at the Orange Tree Theatre in 2014, Bennett brought “An Octoroon” to the venue this year. After positive reviews, its run was extended to July 1 of this year.

The audience sits in the round, at both stage and second tier levels. With the stage floor being pulled apart board by board in the second act, and actors climbing up into the second tier and running through aisles, placing props into the laps of audience members, not a moment goes by without something unexpected to focus on. At one point, two characters argued above me—one dropped a mallet onto my lap, walked away and came back a few minutes later to grab it.

The play opens with an actor portraying playwright Jacobs-Jenkins in his underwear, telling a story about a conversation with his therapist. He is frustrated with the stereotypes and difficulties that come with being a black playwright. From there, another actor playing Boucicault enters, and the two begin a screaming match of “F*ck you!” Discomfort spreads through the audience, both from those who understood what was going on and from those who did not. For an introduction, it doesn’t come with much explanation; the significance of the discord between the two playwrights comes out as the story unfolds.

Before the action starts, Ken Nwosu (a black man) applies whiteface, Danny Wolohan (a white man) applies redface and Alistair Toovey (a white man) applies blackface. Each man sits onstage while “transforming;” there is a solemnity in the action of the painting. It is deliberately shocking, but makes its point in setting up the theme of the play.

“An Octoroon” tells the story of Zoe (played by Iola Evans), who is one-eighth black. She has lived a life of relative privilege and comfort for someone of her ethnicity as the light-skinned daughter of a plantation owner. Upon her father’s death, it is revealed that the paperwork marking her free is void—she is a slave.

When the property of the plantation (including the slaves) is being sold, Zoe is there with them. She sits through the auction alongside Minnie (Vivian Oparah), Dido (Emanuella Cole), Grace (Cassie Clare) and Pete (Alistair Toovey), the four slaves who had been left out of the plan to escape before the auction.

Zoe is the last to be sold. The bidding is held between Dora (Celeste Dodwell), a southern belle and heiress, M’Closky (Ken Nwosu), an evil slave owner, and George (Ken Nwosu), a plantation owner desperately trying to save Zoe from M’Closky. There is an almost forced humor in the scene, until the actors pause and wheel out a projector showing the image of a lynching. In an instant, the audience is ripped from the trance of the show and the reality of what has just occurred on stage is brought to light. The slaves at the auction were characters, but their stories are based on truth.

After that, the show jumps abruptly back into action. In a condensed and narrated version of Boucicault’s original spectacle, the truth comes out and crimes are revealed through a trial. Nwosu, playing both an anxious George and furious M’Closky, jumps back and forth in a brilliant fight scene between the two roles, changing between a hat and mustache or a wig to clarify who he is in each moment. The hilarious and impressive act ends with the death of one of his characters.

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins uses “An Octoroon” to portray not just the struggle of being a black playwright, but of how people react to racism. According to Jacobs-Jenkins, “Boucicault deliberately drew on the theme of slavery and racial tension in the deep South.” “An Octoroon” brings that to the forefront, forcing thought and consideration. It is a play worth seeing if, in the words of Jacobs-Jenkins, you want to “feel something.” Walking out of the Orange Tree Theatre, I felt overwhelmed and somewhat bewildered, but I knew I had enjoyed myself and that I had felt something—which is all a play can ask of you.