The Downsides of Closing Guantanamo Bay

June 9, 2011

Published: February 12, 2009

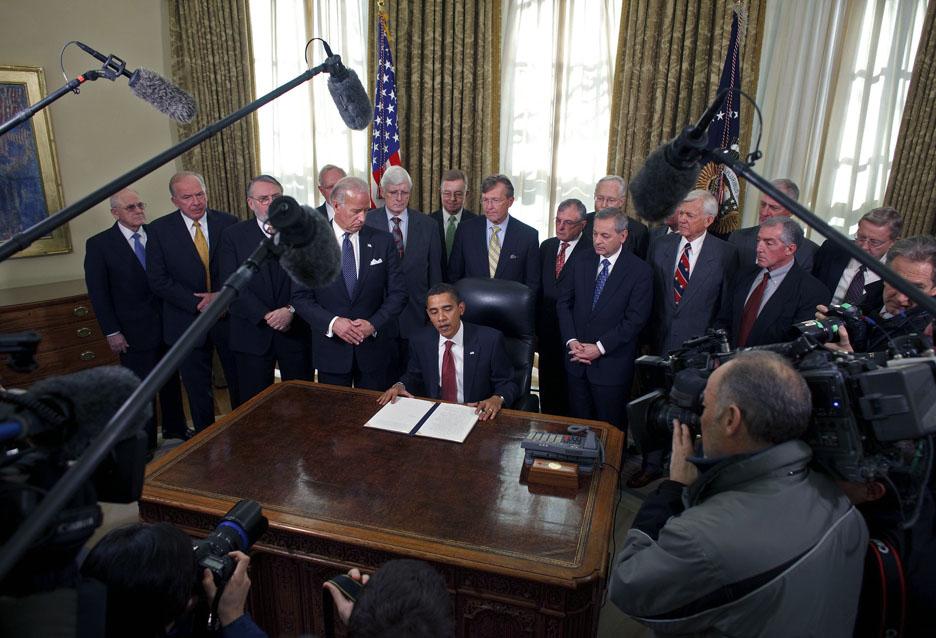

Within his first two days in office, President Barack Obama signed an executive order to shut down the United States Naval Station in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba in one year, necessitating swift action regarding the 245 detainees who remain in the camp. Officials must determine whether the detainees should be transferred, released or prosecuted. Obama’s orders are aimed at closing down a whole network of secret prisons after several reports of cruel and inhuman conditions of isolation. In a 2007 report, Amnesty International said that “many have been held for over five years without charge or trial or knowing if and when they will be released.” As negative attitudes brewed over the camp’s questionable practices, during last year’s presidential campaign, Obama pledged to shut down the site if elected.

But Obama’s quick decision has many complications, and there is no succinct plan concerning how to handle the number of unclassified individuals.

Matthew Waxman, a professor at Columbia Law School, argued in January that “while [the heinous nature] of torture will strengthen President-elect Obama’s conviction that Guantanamo must be closed, they won’t make [the closures of these detention camps] any easier.” The camp should only be shut down after there is a clear plan drafted for the remaining prisoners.

When former president George W. Bush decided to keep the prison operating, he outlined practical reasons for not shutting the camp down.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, lawyers for the Bush Administration said, “Military commissions are required because of the security threat posed by these prisoners, whom they define as ‘unlawful’ or ‘enemy’ combatants, and the sensitivity of the evidence presented, which could endanger U.S. personnel in the field and hinder intelligence gathering.”

And security threats continue to be a problem. After Obama administered the executive order to close, the risk of doing so quickly came to light. The New York Times reported that two former detainees revealed their old Guantanamo docket numbers to the camera in a recorded statement; they appear to have joined Al Qaeda’s Yemeni branch. In their video, Said Ali al-Shihri, who was released from the American prison camp at Guantanamo in November 2007, revealed himself as the new deputy leader of Al Qaeda’s Yemeni branch. He is suspected of playing a role in a deadly attack on the American Embassy in the Yemeni capital of Sana in September of last year. He was sitting with Mohamed Atiq Awayed al-Harbi, who was released to Saudi Arabia in November 2007.

Developments like this suggest that many of the detainees that were arrested may pose a new threat to the United States because they may regroup and channel their hatred of Americans into newly formed and existing terrorist organizations. Even detainees who were not particularly dangerous when they were sent to Guantanamo may have been radicalized by their experiences. Ayman al-Zawahiri, Al Qaeda’s number two, was once more or less an idealist Egyptian revolutionary until he was tortured in an Egyptian prison. He was so outraged and maddened by his experience there that he became a mass murderer, preaching a doctrine of death toward Americans. The detainees in Cuba may follow the same pattern.

As we begin to understand the problems posed by the camp’s closure, many analysts have suggested the creation of a new “national security court”—a specialized tribunal—that would provide fewer due process protections than those guaranteed in ordinary criminal courts and may potentially detain dangerous suspects without criminal charge. However, Susan Crawford, the acting director of the law and security program at Human Rights First, argued that “a creation of a national court system would be a replica of the same system used by the Bush Administration and may also fuel more terrorism.”

Clearly, there is no easy solution for the end of Guantanamo. Even though the camp has been a rallying point for anti-American sentiment worldwide, disbanding it entirely is too dangerous. The closure of Guantanamo Bay leads to speculations that a few of the prisoners will end up on American soil and commit more acts of terrorism in the future. Many Americans worry that terrorists will be allowed to get off on legal technicalities and be released. As suggestions linger with the handling of detainees, it seems that there is no clear solution. We remain uneasy and seek refuge in security, but Obama must decide what to do next.