This Is Your Brain Unplugged: How We Connect With Our Computers

June 1, 2011

Published: Febrary 14, 2008

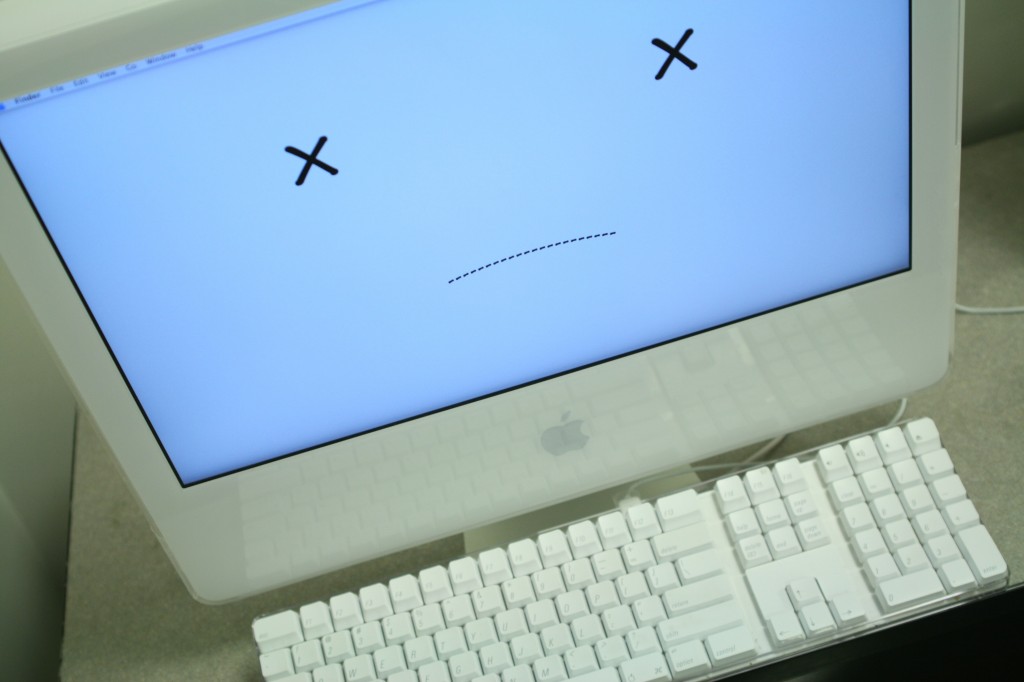

Evvers, the Costa Rican tech support guy, had me unscrew the back panel on my laptop, but I already knew it was too late. My machine had died—again—and I would be forced to send it in for repairs. My first few weeks of the new semester would be spent without a computer—offline, unplugged, disconnected.

Without a computer and an Internet connection, my room feels more like a big closet with a bed: I dress there and sleep there, but I can’t really do anything there. Instead I stumble around, operating on a more limited, basic level. I eat, I sleep. I go to class. I visit friends and play video games. I try to remember to do my homework. I have trouble thinking though, at least the way I’m used to.

I get by, of course. I check email and Facebook when visiting friends’ apartments, and I come here, to the library, to write papers. I have even managed to mostly read the news and keep up with a couple blogs

Still, it’s a hassle. Computers may be getting more and more common, but they aren’t quite ubiquitous enough yet to make not having one of my own a seamless experience. Staying connected with friends and family and the ever-accelerating flow of information and ideas that is the Internet becomes something that I have to go out to do. I may manage to dab up a few of the day’s tidbits of Web culture, but it is hard to really surf on a machine unless you feel comfortable with it: your browser, your bookmarks, your settings, your headphones to listen to audio with and your hard drive to save files on. It all just goes faster, more naturally, on your own machine. Following links or performing searches can have a certain rhythm, a heartbeat of practiced clicks and keystrokes.

In his short story “Tourist” (later included in his novel “Accelerando”), hard science fiction writer Charles Stross describes a 21st century renaissance man, Manfred Macx, who is mugged of the wearable devices that record his experiences and connect him to the host of software that helps him find and analyze information. We may not wear such things just yet, but not having my computer makes me realize just how big a part of how many of us learn and think the Internet has become. If we are in the same room as our computers, vast amounts of information become so quickly accessible that we might as well be remembering memorized facts. When an idea or a question hits, my instinct is to search. If I hear a phrase, name or term I don’t know, I can just Google it, Wikipedia it, IMDb it. When a URL becomes a verb, the change in language is not simply a matter of popularity, but rather a case of the Web site becoming so integrated into our behavior and thinking that it is functionally a part of our individual minds.

What we are seeing here—and what I’ve felt so cut off from since my computer died—are the first hints of people developing what are sometimes called exocortices. Ben Houston, the researcher who coined the term, defined an exocortex as “an organ that resides outside of the brain that aids in high level thinking.” When we interact with computers so richly and quickly—recording and broadcasting our thoughts and moods, calling up previous recordings, answering our questions and pursuing our ideas—that the difference in latency between Googling on our computers and thinking and remembering on our built-in nervous system becomes increasingly negligible, can we really say that the two are completely separate?

When Manfred lost his exocortex he lost significant portions of his memories and identity. He wandered around Edinburgh in a daze, unsure of who he was or what he was supposed to be doing. Compared to this, my recent ennui about losing my computer seems pretty trivial, but not entirely of a different grain. Like Manfred, I was disconnected from one of the main tools I use to organize my life, and there is something about this that can be deeply unsettling. At the moment, we can only really plug in to our little burgeoning exocortical structures around computers with high bandwidth connections, but with the proliferation of increasingly sophisticated mobile Internet devices like iPhones and Blackberries and subnotebooks, it doesn’t seem like it will be long before we are always online, always enhancing our own knowledge with the instant libraries of cyberspace. Over the next decade, these technologies will no doubt advance and become more a part of how we live our lives. As how we store and deal with information changes, I can’t help but suspect that maybe our brains might be changing a little bit too.