Race Doesn’t Define My Identity, Yet the U.S. Census Allows It To

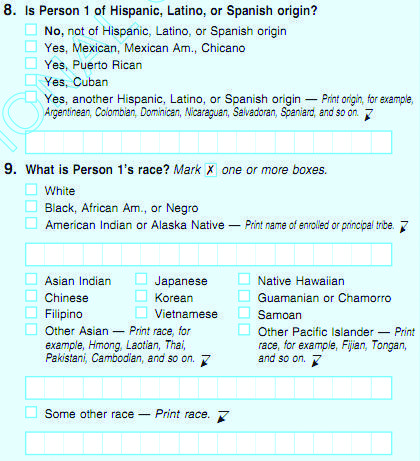

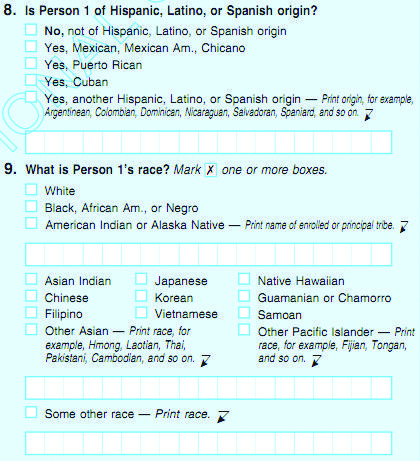

When confronted with the question of race, some citizens are forced to categorize themselves as “other” on the U.S. Census. (Courtesy of U.S. Census)

February 1, 2012

Unlike Latinos, I don’t belong to an exponentially growing community in the United States. Unlike Latinos, the 2010 U.S. Census did not concentrate on my ethnic identity and place of origin. A question on the Census asks, “Is Person 1 of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin?” As a Middle Eastern American, I wish I could have received such courtesy. Regardless of this lack of attention, the next question on the Census suddenly forced Latinos reluctantly into obscurity alongside me.

The recent New York Times article “For Many Latinos, Racial Identity is More Culture Than Color (Race)” by Mirya Navaroo explores the U.S. Census’ contradictory identification of Latinos by ethnicity and then by race. Race, unlike ethnicity, is an illegitimate social construct and a codified categorization of people based on skin color and only limited geographical sites. In response to being asked for my race, what am I, a Middle Eastern, supposed to say? Alongside 18 million Latinos, I filled in the “other” circle for the race question in the 2010 Census because I, too, am socially conditioned to attribute myself to racial anonymity.

I grew up in a homogenous community in Connecticut and my family and I were never treated or identified as being “white/Caucasian.” We were regularly “othered” by our community for our Persian heritage and Islamic spirituality. I am proud and intimately involved with my Middle Eastern ancestry. As a result, I became determined never to succumb to abandoning my heritage in order to assimilate into the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant majority of hometown. When it came to state tests, the SATs and the national census, defining myself as “white/Caucasian” was incongruent with how others and how I perceived myself.

Through Fordham’s own Dorothy Day Center for Service and Justice, I participated in an anti-racism workshop with The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond, where I learned about the etymology and the history of the concept of “race.” I was informed about how the Virginian settlers first implemented the category of “white” in 1609 as an obvious way of highlighting differences between themselves and the indigenous natives.

Soon race became a prevailing discourse in the wake of the Scientific Revolution (16th-17th century). Thinkers like the Comte de Buffon and Johann Friedrich Blumenbach then famously expounded upon it by defining the races as Caucasoid, Negroid, Australoid, Mongoloid and Indigenous Others and their corresponding colors (White, Black, Brown, Yellow and Red).

During this workshop I realized that the entire region of the Middle East and North Africa (which according to contemporary academic standards consists of approximately 20 countries) was conspicuously disregarded. My ancestors and I were completely overlooked. We were never placed in any of Blumenbach’s traditional categories of race. Historically my people were forced into racial anonymity. This observation only augmented my understanding of the illegitimacy of race.

The 2010 Census, in addition to listing several of Blumenbach’s traditional races (white, black), lists nationalities and ethnicities ranging from Japanese to Samoan to Native Hawaiian under the question: “What is Person 1’s race?” As a Middle Eastern-American this infuriated me. The United States is a force behind two insurgencies and a player in multiple soft wars in the Middle East, and yet they can’t even present us with a measly circle in the national census?

Regardless of what the Census is designed to do, I will not be forced to choose between obscurity and ascribing myself to a group I share no similarities with. The U.S. government can bomb the Middle East and my region of ancestry, but they can’t formally recognize my Middle Eastern ethnicity?

During my Global Outreach trip to the Dominican Republic (DR), I learned theirs is an ethnically tripartite society (indigenous base with African and European additions). My team and I learned that in DR the government does not formally recognize race. Professor Lynne Guitar of the Pontífica Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra, who gave us a lecture of colonial history, explained in turn that this lack of race identification enables the government to overlook the conspicuous discrimination against Haitians.

This assertion by Guitar made me appreciate America’s systemic use of race as a dominant category of identity, but only to a degree. At least the use of race is a tool for identifying and combating bigotry. However, this only helps those who are recognized as a race by the U.S. Census. What about my fellow Middle Eastern Americans who are pushed into obscurity?

The U.S. Census is a reflection of how institutions throughout our country codify race and perpetuate its dominance as a form of identification. Consequently, this issue transcends the Latino community. I do not want to be continually “othered.” My community and ethnicity is not attributed to a race. I am proudly of Middle Eastern ancestry and I will not let a political institution or a class peer force racial anonymity upon me. As a result, I demand that the U.S. Census recognize my identity and others outside of race.