There is a clear and provocative issue plaguing university classrooms. It seems almost naturalized; a universal element of the academic ecosystem seemingly unaware of its existence. The truth is apparent: many students are not learning and do not seem to care to.

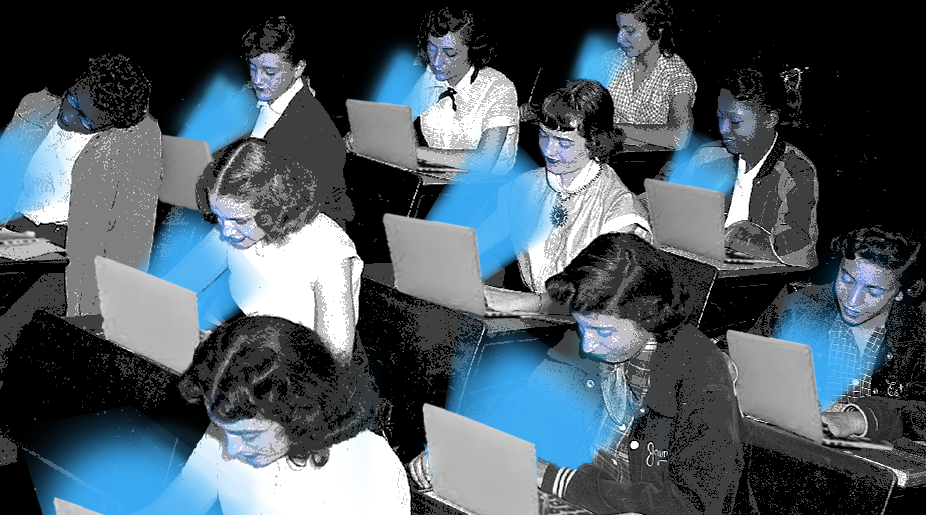

When I walk into a classroom, I am faced with a wall of screens. This in itself is not a problem; many excellent learners take digital notes and do well — I often participate in digital note-taking myself. But I have found that when I situate myself in the back of a classroom, I do not see note-taking on many screens. Instead, I see a plethora of online shopping, AI writing essays for other classes and New York Times games. Too many university students treat their time in the classroom as a sentence to be served; educational enrichment is seemingly an afterthought.

The naturalization of this phenomenon both affirms its existence and identifies its route to actualization. Computers, more commonplace than notebooks in university classrooms, are the arbiter of student disaffection and tandemly provide students with a medium of distraction. It is no new critique that technology in classrooms can distract students. That said, I believe it significant to recognize that at Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC), technology does not seem to merely distract students, but actually shapes a mindset that impacts their educational outlook both inside and outside the classroom.

It is one thing to be prone to distraction or an occasional glance away. I can be found checking my email or text messages at times, although I am making an effort to ameliorate this. It is an entirely different habit to toil away an hour of class time looking for new clothes or curating a Pinterest board. The prior maintains the student’s overall place in the classroom, while the latter entirely removes them from the classroom environment in a grand act of escapism.

The critical distinction between mere distraction and escapism is based on mindset. The mindset is based on disaffection, which leads to a lack of care for their education and a general ambivalence towards educational structures.

This mindset, in turn, requires one to disregard both the practical and moral ramifications of classroom escapism. Perhaps the most compelling of the practical elements — that, in this mindset, is necessarily ignored — is the monetary cost. Within the per-credit rate for part-time students and a fixed rate for full-time students, a single credit at FCLC is $2,100 for a part-time student, with tuition being $31,495 per semester for a full-time student. My interpretation of these figures for a full-time student is thus: if one goes to Philosophy 1000 — a three-credit class — twice a week and splits their time between online shopping and text messaging, they are spending more than $5,000 on curating a shopping cart and not learning anything.

The idea of the classroom as a primarily collaborative space seems to have vanished in favor of a perceived performer-audience dynamic.

While there are other physical costs of classroom disaffection, more important to me are the moral consequences, one being a total denigration of the classroom ecosystem. Via general will, presence becomes optional; thus, participation and engagement face the same fate. The professor becomes a mere background buzzing, the final barrier to total displacement. Group work is individualized, and conversation is unthinkable. Readings, as real-world remnants of the pre-escapist classroom, become optional at best but more popularly irksome and treated as almost oppressive.

Perhaps due to online schooling during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the idea of the classroom as a primarily collaborative space seems to have vanished in favor of a perceived performer-audience dynamic. The professor is merely there to perform education to a smattering of non-collective students. Through the simple act of participating in classroom ignorance, disaffected students actively denigrate the long-held structure of the classroom that seeks to use participation and thought to enrich every person in the room.

Why are we in this situation? The lingering effects of the COVID-19 quarantine are undoubtedly relevant and to be thoroughly analyzed in the future. However, specific to FCLC, I believe it is more prudent to analyze recent critiques and changing characters of the FCLC classroom in pursuit of a Fordham-specific explanation.

If arguments for self-enrichment taught in philosophy and English courses land on deaf ears, how can the student improve?

Recent critiques have identified an allegedly outdated (or at least in need of rehabilitation) core curriculum as an origin of perceived student disaffection. I believe that this is a misidentification and may even be interpreted as a result of a broader student apathy. While there are arguments for the rehabilitation of FCLC’s core, some of which hold merit, this issue of student apathy stretches far beyond the core classroom. Apathy of this sort is most apparent in universally required courses — particularly those that are deemed “too specialized” or “irrelevant,” such as philosophy and history classes — but it is evident in courses of varying levels and specialties.

From 2013 to 2023, FCLC student grades matched a trend of grade inflation in higher education, wherein students achieved higher marks for the same or comparatively worse work. Such treatment breeds the disaffection and apathy discussed. Why should students work hard if they can get the same grades with lesser quality work? If arguments for self-enrichment taught in philosophy and English courses land on deaf ears, how can the student improve?

The dominance of technology unsurprisingly bolsters issues of disaffection and escapism. Not only can disaffected students get by, but they can actually tune the irksome drone of enrichment out in favor of the internet.

Identification of students uninspired by course content and capable of maintaining high GPAs without comparable effort paints a problem with a complicated solution. A certain level of responsibility falls to the university to raise academic standards in an attempt to invigorate the student body. Strict rules of this manner are not always effective — think of Fordham’s seemingly strict but actually malleable absence system. Professors cannot be expected to solve this problem alone; there is a plethora of engaging and highly intelligent professors at FCLC, all of whom have classrooms filled with absentees to some degree.

What then, can solve the problem of apathy and classroom escapism? The unfortunate truth is that the answer lies with students. Escapees must identify what breeds their disaffection for education and actively fight it. It may be an attention span diseased by TikTok or an over-reliance on AI fomenting subsequent insecurity in their own abilities. My most pessimistic worry is that classroom apathy is due to a lack of student appreciation for education — perhaps a misunderstanding of just how lucky one is to receive a university education at all. Regardless of the root cause, the burden falls on the student to take responsibility and prioritize their own education.

Learning is difficult, life is difficult. Breaking habits is difficult and so is building new ones. However, the university experience is not meant to be easy, and it should not be skated through. There has perhaps never been a more irresponsible time in history to neuter one’s own rational abilities. The consequences of apathy and disaffection have never been more clear. Breaking out of apathy is radical in a scape so intent on escapism. The simple act of situating oneself in the classroom on all levels of being bears an air of community — as escapism denigrates the classroom, presence enriches it.

Amidst all this blithering, what do I propose? Nothing more than a simple recentering: Use a notebook in class, do the readings and put away your phone. Go to the library, ask your professor questions and engage actively in class. Write your own essays, and ask the person in the seat next to you their name. Reject apathy, reject disaffection, reject escapism. Care about what you do, take responsibility for yourself, and through that, take responsibility for everyone.