For many young people, the American collegiate experience serves as an eye-opening window into class divides. Seemingly innocuous fundamentals of college life — such as dorm room decorations or “going-out” wardrobe choices to more serious undertakings like choosing housing accommodations — are revelatory of students’ varying financial statuses.

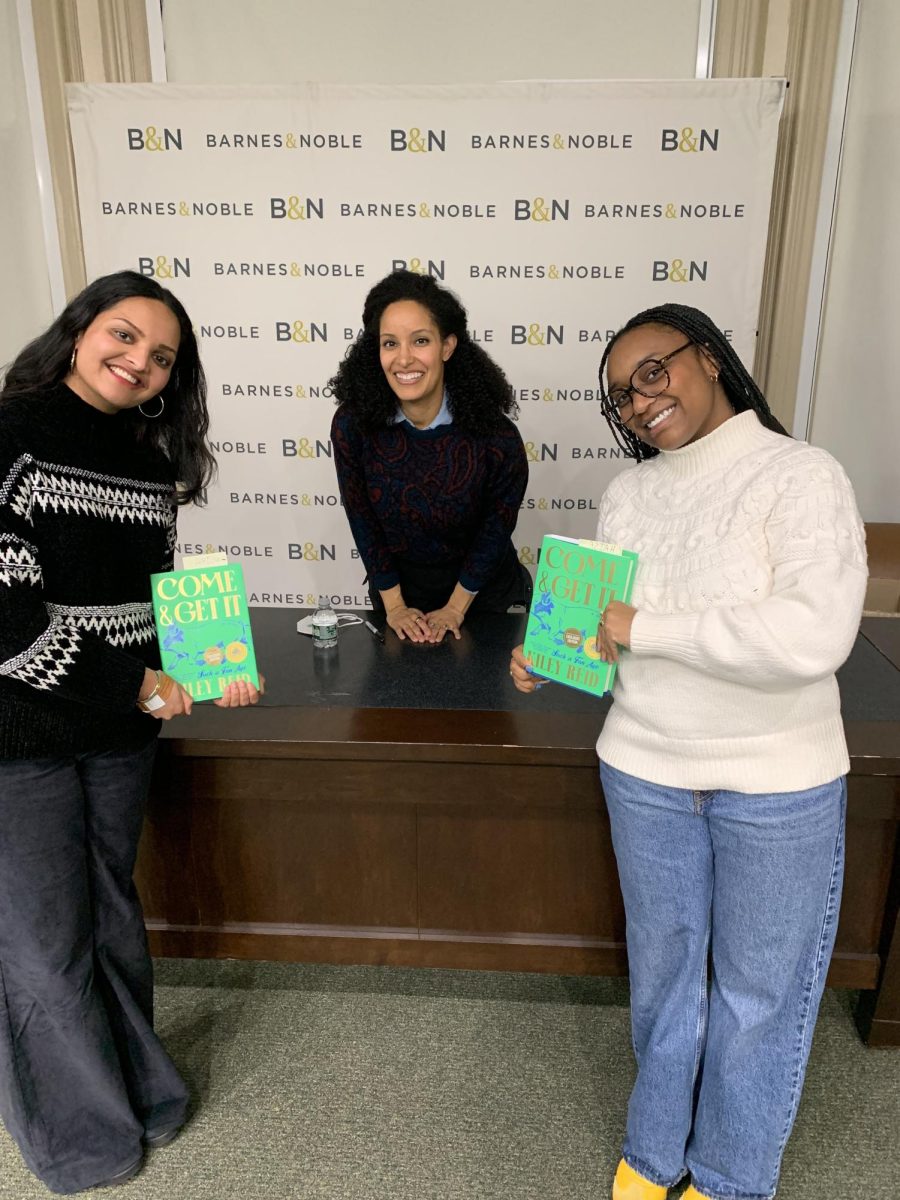

In her sophomore novel, “Come and Get It,” American author Kiley Reid explores both money and power, and how they impact those who have them, and those bereft of them, set against the backdrop of a large southern university in Arkansas.

Reid made waves in 2019 with her debut book “Such a Fun Age,” a witty and captivating read that also addressed race and class.

In “Come and Get It,” Reid hones in on young women and their relationships with money. The protagonist, Millie Cousins, is a 24-year-old resident assistant (RA) at Belgrade Hall, an upperclassmen, transfers and scholarships dormitory at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Her prudent personal finance habits attract the admiration of Agatha Paul, the book’s other main subject.

Millie is diligent, financially independent from her parents and committed to her RA gig. Agatha, on the other hand, is a chic journalist from Chicago who recently ended a relationship with Robin, a dancer. The pair often argued about money and Robin’s seeming financial dependence on her.

She then arrives in Fayetteville to study young southern women’s thoughts on weddings. Millie serves as the catalyst for Agatha to meet three college girls equipped with the irreverence, presumption and contrarian spirit of adolescence. When one of the interviewees, Jenna, wears a blanket over her head, she remarks that she resembles “a cute little refugee.”

As the conversation progresses, Agatha cares less about the women’s thoughts on weddings and more about their relationship with money. Jenna, who works in her dad’s orthodontist office, receives “practice paychecks” from him and earns her “fun money” (money for discretionary expenditures) from a job at alumni services. Agatha may not be fond of the women, but she sure does like listening to them.

Young women of differing socioeconomic backgrounds candidly, and sometimes brazenly, recount their thoughts on social status, class and college life to an academic researcher.

So, Agatha shifts her focus from southern women and weddings, to a series for “Teen Vogue” profiling young college women and their approach to money. She does so with the help of Millie, who agrees to let Agatha listen in on the chit-chat between the young women from her room for story material.

Reid drew inspiration from a study by Laura T. Hamilton and Elizabeth A. Armstrong titled “Paying for the Party: How College Maintains Inequality.” In the study, Hamilton and Armstrong chart the trajectories of a group of women at an unnamed “moderately selective” public Midwestern university who begin their college careers in the same dormitory first year, and end up with vastly different outcomes.

The study shows how socially oriented students from financially sound backgrounds who can choose the “party pathway,” a route fastened in the Greek Life system and supported by administrators (due to the economic advantages they present), often see the most economically successful results.

The throughline between Hamilton and Armstrong’s study and Reid’s plotlines are explicit. Young women of differing socioeconomic backgrounds candidly, and sometimes brazenly, recount their thoughts on social status, class and college life to an academic researcher.

Through masterful and realistic dialogue, Reid allows us to look past the lack of discernible plot devices in the book and instead lets us simmer in the lives of these complex, well-constructed characters.

Reid is, at her core, a spectator. She is a master of biting one-liner descriptions, describing one character as resembling “a backpack.” Her realistic dialogue reveals interesting truths about young women and their consumerist patterns, whether it be Uber trips, indulging in brands such as La Croix and Birkenstock, or particularizations of dorm decorations like Himalayan salt lamps.

Her strengths lie in crafting well-meaning — yet deeply flawed — characters, some of whose actions make the reader want to dive into the text to grip and steer them in the opposite direction, while being simultaneously enchanted by the embarrassment their next move will create. Reid skillfully and nonjudgmentally introduces us to a diverse array of young women.

One of the novel’s most compelling and pitiable characters is Kennedy, a lonely transfer student from Iowa who shares a suite with Tyler and Peyton. After experiencing a traumatic incident at her previous school and being relegated to a social pariah, Kennedy is plagued by an overthinking mind that hinders her from integrating into campus life at Arkansas. Reid’s vivid descriptions of Kennedy’s internal thoughts make her one of the novel’s most sympathetic characters.

Through masterful and realistic dialogue, Reid allows us to look past the lack of discernible plot devices in the book and instead lets us simmer in the lives of these complex, well-constructed characters.

Ultimately, the novel’s conclusion falls short of the build-up that Reid establishes. By attempting to neatly resolve each of the character’s faiths, she unintentionally glosses over major events instead of engaging in a more realistic conclusion.

The novel succeeds in identifying and recognizing the financial gaps that higher-educational institutions perpetuate. She does so by highlighting the difference between students who casually discard money and travel by Uber across campus, versus the more financially prudent students, as well as bringing to light how access to money and financial wealth can affect individuals’ dispositions and confidence.

Reid doesn’t make any sweeping normative statements on American consumerism, rather, she details, with realism, empathy, compassion and some cringe, her character’s desire for and reliance on money in even the most minute ways.