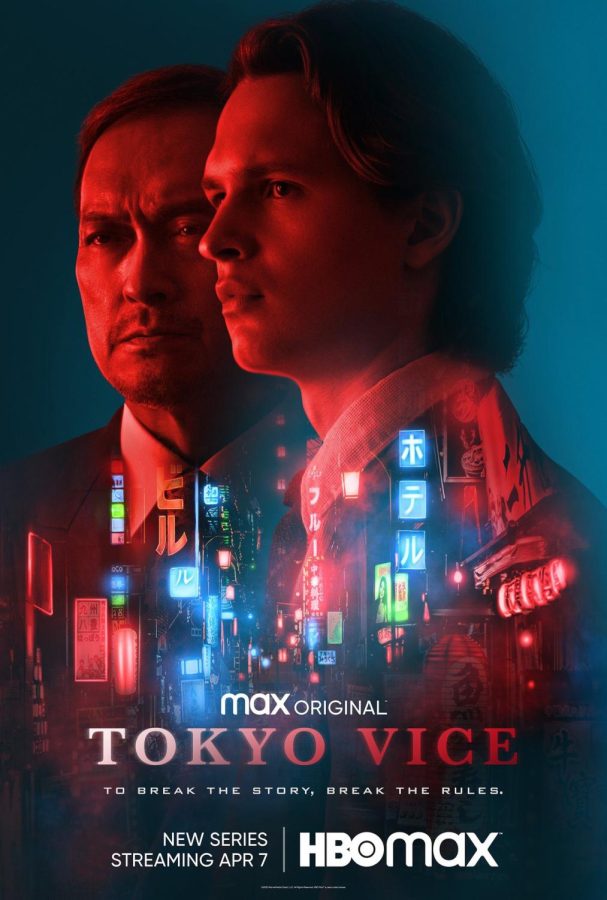

‘Tokyo Vice’: Uncovering the Dark Side of Japan

Based on a true story, an American crime drama that uncovers a unique and flawed side of Japan: investigative journalism, bureaucratic corporate culture, and of course, the yakuza

WOWOWINC VIA CREATIVE COMMONS

“Tokyo Vice” focuses on the protagonists relationships with melodramatic characters.

November 14, 2022

The HBO Max series “Tokyo Vice,” based on Jake Adelstein’s memoir of the same title, navigates the audience through the endlessly fascinating streets of late-1990s Tokyo. Loosely based on a true story, this eight-piece series, which was released in April 2022, makes for an intense and highly entertaining show for Western and Japanese viewers alike.

The filming took place in Tokyo, developing an authentic depiction of the city. The neon-lit building facades and shadowy backstreets are located around the intersection of the notorious entertainment districts of Kabukicho, Roppongi and Shinjuku.

Although the lyrical portraits of these locations compel the audience to revisit a foreigner’s adventures, they also warn that life in Tokyo is not as perfect as it seems, which is why Japan is often called the land of contradictions. Away from the public eye, things are quite different than they appear.

Ansel Elgort — who is known for other films such as “Baby Driver” and “West Side Story” — takes on the role of Jake Adelstein, an investigative reporter whose excellent proficiency in Japanese and fascination with the yakuza, Japanese organized crime syndicates, enable him to move from Missouri and become the first foreign-born journalist for the Yomiuri Shimbun, one of the top newspapers in Japan.

Dedicating himself to learning Japanese and on-the-ground reporting in order to immerse himself in the role, Elgort brings forth an appealing portrayal of a newbie investigative journalist: ambitious, driven and fearless, but at the same time, impatient and slightly egoistic.

From the pilot alone, the reality of living and working in Tokyo becomes crystal clear to not only the protagonist but the audience as well. For those unfamiliar with Japanese journalism, it has one of the lowest levels of freedom of expression and freedom of the press.

Almost an entire generation of Japanese crime reporters, in both the drama and real life, do the exact same thing — rewrite police press releases and merely report the official version of the events. Those who do not follow the rules are “meiwaku,” meaning one who burdens or causes inconvenience for others. Japanese reporting is basically the antithesis of the saying “There’s always more to the story.”

A man impaled on a sword, a man setting himself on fire and a woman committing suicide: These are the first few incidents the protagonist reports on. Despite his insistence to his staff that there is more to the story, he is oftentimes chastised for doing the one thing crime reporters are supposed to do: report the truth.

Watanabe, having played mentor-like roles in films such as “The Last Samurai,” portrays Hiroto as a resourceful and pragmatic character who uses Jake’s disposition as a means to take down the yakuza.

“There is no murder in Japan.”

This is what Jin Miyamoto (Ito Hideaki), Jake’s first liaison in the police department, tells the protagonist when asked why the police and media report these incidents as “unexplained deaths.”

In the 1990s and up through the 2000s, Japanese newspapers and publishing companies adhered to a reporting style that was limited and aimed for impartiality, focusing only on the four W’s: Who, What, When and Where. There is no Why. They tended to shy away from controversial topics, such as murder, out of concern for public sentiment.

“Tokyo Vice” is not ashamed to highlight such flaws of Japanese journalism, as Jake describes it as “mentally tyrannical.” Jake’s deviation from this rigid newspaper system is what makes him an interesting character in this story.

The focus of this drama, however, is not only on the protagonist but on his relationship with more traditionally melodramatic characters, each of whom symbolize underrepresented yet highly (in)visible elements of Japanese society.

One involves Hiroto Katagiri (Ken Watanabe), a veteran detective who is unwilling to turn a blind eye to what is happening with the yakuza yet frustrated with the police’s lack of ambition to rid the city of crime. Watanabe, having played mentor-like roles in films such as “The Last Samurai,” portrays Hiroto as a resourceful and pragmatic character who uses Jake’s disposition as a means to take down the yakuza. But at the same time, Watanabe exhibits the compassionate side of his character, acting as a father figure for the protagonist.

Another relationship involves Sato (Sho Kasamatsu), a yakuza member whom Jake befriends over a common interest in singing “I Want It That Way” by the Backstreet Boys.

Here we get to see a humane side of a yakuza member due in part to Sho’s performance. He creates an indelible portrait of a man whose good heart clashes with the reality of criminal life. His hesitation to take up the yakuza lifestyle is perhaps most telling.

Eimi Maruyama (Rinko Kikuchi) attracts the audience with her role as Jake’s strict editor and supervisor. Her dualistic portrayal as both a woman and a “Zainichi,” or ethnic Korean, represents the critique of certain aspects of Japanese culture that have yet to be resolved since the 1990s, relating to patriarchal hierarchies, xenophobia and sexism.

With an unexpected cliffhanger and the announcement of a second season in 2023, “Tokyo Vice” shares a glimpse of the dark side of Japanese society.

Her willingness to hide her background from her staff, excluding Jake, reminds the audience of the existence of ethnic minorities in Japan within the context of a complicated and often hostile relationship between Japan and Korea, which has previously been seen in Apple TV+’s “Pachinko.”

Samantha Porter (Rachel Keller), an American club hostess with whom Jake was smitten, exemplifies the harsh reality of living in Tokyo as a foreigner. Her performance as a foreign woman whose goal was to escape her hometown and live independently, only to ironically end up lost and alone in a city where she is treated as a second-class citizen, is heartbreaking.

The more the series progresses, the more we learn about the criminal underworld. In the 1990s, Japanese and Western filmmakers originally embraced the gangster genre’s macho romanticism, depicting the yakuza as rebellious, cool and chivalrous.

“Tokyo Vice” delivers a raw depiction of the yakuza by not shying away from exhibiting the vividness and brutality of their crimes. We also learn how the yakuza have imbued themselves into almost every sector of Tokyo, from the entertainment district to the decision-making of the police authorities. They exist out in the open; they have offices, business cards and fan magazines. The dualistic nature of the yakuza as both sources and enemies of Jake’s attempts to uncover the underworld is what makes their role in the show enticing.

With an unexpected cliffhanger and the announcement of a second season in 2023, “Tokyo Vice” shares a glimpse of the dark side of Japanese society. If anything, the drama will continue to show the audience the hidden side of Tokyo where nothing is what it seems, whether it be the police, reporters or, of course, the yakuza.