Time Landscape: An Ode to 17th-Century New York

Alan Sonfist’s Time Landscape serves both as an ode to natural Manhattan as well as a timeline of history

Time Landscape opened 13 years after Alan Sonfist proposed the project to the city.

October 28, 2022

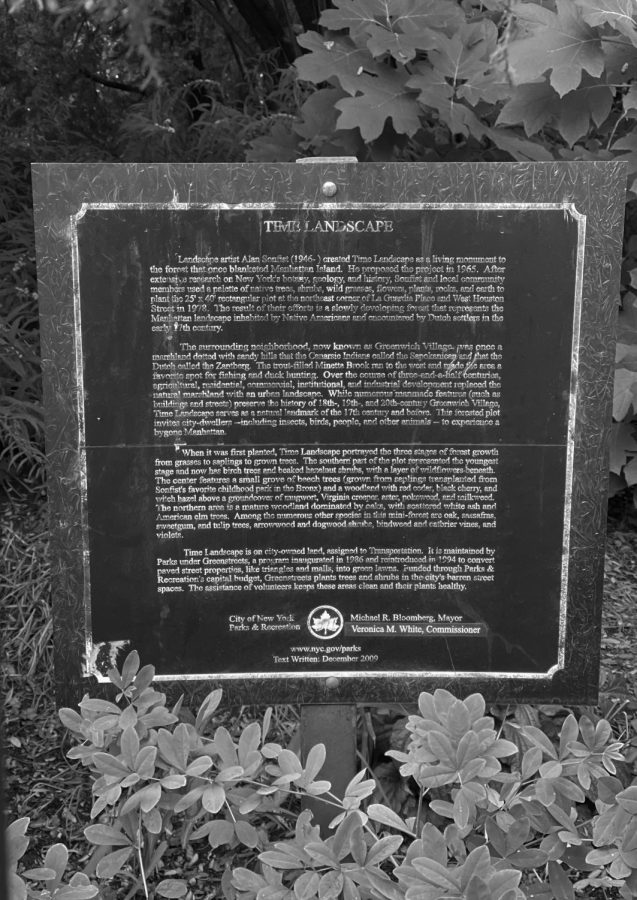

The Time Landscape was created by Alan Sonfist in 1978 in honor of the forest that used to live over Manhattan Island. This landscape, which lies on the corner of West Houston Street and LaGuardia Place, is meant to be a representation of the native natural life once present in New York.

According to the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, the landscape portrays “three stages of forest growth from saplings to grown trees.” In its original rendition, the plot of land’s youngest stage of growth lived at the southern part, with birch trees and hazelnut shrubs. Red cedar and black cherry trees lived in the center of the plot, and oaks and elm trees could be found in the north.

This space isn’t just meant to highlight the natural growth of what used to be Manhattan’s forest. It is also meant to represent the landscape that was inhabited by Native Americans in the early 17th century.

The area that is now known as Greenwich Village was once filled with sandy hills called the Sapokanikan by the Canarsee Indians. The Minetta Brook ran through the western part of the area and served as a hub for fish and duck hunting. Multiple plants grew there, such as elm trees, tulip trees, bindweed and dogwood shrubs.

As the years went by, the integrity of the space that was once inhabited by Native Americans began to fade away, and the land was filled with residential, commercial and industrial structures that erased any trace of the Manhattan that was before.

In a lecture at the XIV International Forum, Sonfist expressed that the Time Landscape was meant to be “his childhood forest giving birth in lower Manhattan.” Through the years, Sonfist has come to be known as one of the pioneers of the land art movement, which is a movement that uses the natural landscape as a basis for artistic expression.

Alan Sonfist’s Time Landscape is an ode to old New York. It’s a love letter to the 17th century and to those who first lived in the city.

Growing up in the south Bronx, Sonfist expressed anxiety toward the ongoing deforestation in the area, and it is evident that this experience informs multiple aspects of his art. The Time Landscape even contains a small grove of beech trees that were grown from saplings and transplanted from Sonfist’s favorite childhood park in the Bronx.

Looking at Sonfist’s work feels like a memory. Even though the native plants that reside there have since grown in size and become more common around the world, one can still feel the intention and history in the habitat.

“It’s a collage of time,” Sonfist said. “and that’s why I call them time landscapes — because they’re meant to change in time.”

There’s a certain beauty in this, but the journey toward building the landscape wasn’t an easy one.

“When I created the landscape, the lower officials of the city were all afraid of what would happen if I created a wild forest in the city of New York,” he said.

To be able to build it, Sonfist had to agree to put a steel fence around the space because officials were scared of the danger of wildness in the city and the plants’ potential to overtake the surrounding area.

“At first I objected, but then I realized the city was contributing to another way of looking at a forest,” Sonfist said. “Actually, I kind of like the idea of the fence around it now because it creates a viewing arrow into the forest, and that’s a very special way of looking at it.”

Over 40 years later, the nature within Time Landscape still stands tall.

”I still think it’s a miracle that I was able to create a major monument to the city,” Sonfist said.

Alan Sonfist’s Time Landscape is an ode to old New York. It’s a love letter to the 17th century and to those who first lived in the city. It’s like a time capsule that continues to adapt to our current life and stays true to history at the same time. Having this space as a monument to the city is truly a miracle.