Fordham Professor Speaks on Juneteenth and the Haitian Revolution

Wes Alcenat connected the conversation about the struggle for Black liberation to his research and racism today

July 1, 2022

The Office of the Chief Diversity Officer, in partnership with the Offices of Multicultural Affairs and the Provost, sponsored a conversation on June 16 with Wes Alcenat, assistant professor of history and urban, American and African American studies at Fordham. The talk, which was held over Zoom, consisted of a dialogue between Rafael Zapata, the university’s chief diversity officer, and Alcenat regarding the Haitian Revolution and its implications on Juneteenth today.

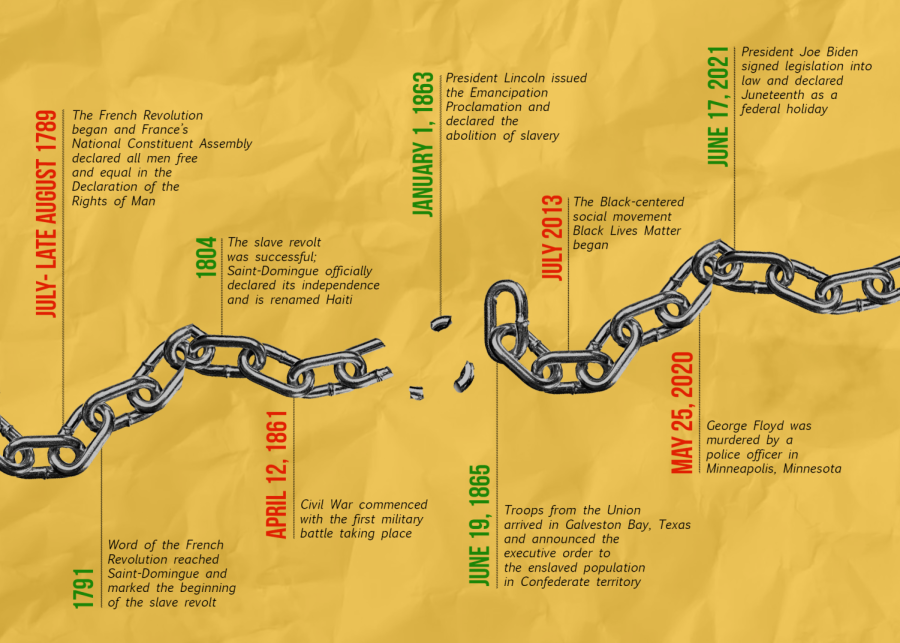

Juneteenth is an annual federal holiday celebrated on June 19 that commemorates the emancipation of enslaved people in Confederate states and the abolition of slavery. Although U.S. President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, freedom was not extended to enslaved Black people in Confederate territories until June 19, 1865, when troops from the Union arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas, and announced the executive order. Juneteenth did not become a national federal holiday until June 17, 2021, when U.S. President Joe Biden signed legislation into law.

The talk also focused on the Haitian Revolution, which Alcenat noted is relevant to Juneteenth due to the suppression of Black freedom. He referred to the news of the French Revolution being kept from enslaved Black people in Haiti and the two-year delay of the Emancipation Proclamation’s announcement to enslaved Black people in Confederate states as examples.

“We have to look at Juneteenth as being directly connected to the legacy of the Haitian Revolution (and) this pattern of trying to undermine Black freedom, even as it actually exists on paper,” he said.

Haiti, formerly known as the French colony of Saint-Domingue prior to its independence in 1804, was heavily relied on by France and the rest of Europe for its robust production of sugar and coffee. This demand led to the exploitation of Black Haitians, who were forced into indentured servitude on plantations.

When word of the French Revolution reached Haiti in 1791, the enslaved Black people of Saint-Domingue saw an opportunity to revolt, led by Toussaint L’Ouverture. The Haitian Revolution lasted until 1804 and is the only instance where an enslaved population successfully overthrew their colonizers.

In his response, Alcenat also highlighted the significance of another one of Haiti’s constitutional principles at the time, which stated that in order for an individual to become a Haitian they would have to first declare themselves Black; this principle set a precedent for Black Lives Matter as a slogan today.

During the talk, Alcenat highlighted the constitutional principles the Haitian revolutionaries were championing in response to the principles of the French Revolution that were “not afforded to nonwhite people.” One of those principles included the automatic guarantee of citizenship to anyone who was of Indigenous or African descent. Zapata connected this extension of citizenship and freedom from the revolutionaries to Black and Indigenous people from the diaspora and asked Alcenat about what this invitation meant to enslaved people in the United States specifically.

“I call it, sort of, ‘Haitian constitutionalism,’ whereby they constructed what I call a sort of a political reparations project that restored, in essence, symbolically, dignity to those who had previously been the indigenous inhabitants of the island,” he said.

Zapata’s question touched on Alcenat’s research, which focuses on the migration of Black people to Haiti throughout the 19th century in the years leading up to the Civil War. In his response, Alcenat also highlighted the significance of another one of Haiti’s constitutional principles at the time, which stated that in order for an individual to become a Haitian they would have to first declare themselves Black; this principle set a precedent for Black Lives Matter as a slogan today.

“What it is saying ultimately is (that) the degraded, the dehumanized, the oppressed, those who are at the very bottom of society, we’re going to reverse this order,” he said. “Those who really do know what freedom is, because they also know what non-freedom looks like, are the ones who are going to define what freedom, what liberty is going to mean from now on.”

Alcenat went on to describe that the assertion of Black freedom as a principle was the most expansive form of freedom that was allowed. He noted that in the context of a discussion on Black liberation, the conversation warrants shedding one’s whiteness in order to identify with those who really know what freedom is because they have lived the experience of not being free.

“It was the most universal and capacious way that they could reframe citizenship and freedom while, at the same time, cutting out whatever the moral hazards of race as a construction would be in the process,” he said.

According to Alcenat, the Haitian Revolution’s legacy recognized the concepts of race only historically without giving any validity to the white supremacist lens.

The second half of the call consisted of a Q&A session with Alcenat. Anne Hoffman, professor of English at Fordham, asked Alcenat about Haiti’s constitutional principles and whether or not they affected discussions of race in the greater context of history throughout the 19th century. In response, Alcenat noted that recognizing people’s history and what that history made of them needs revitalizing. He also outlined the legacies of the Haitian Revolution and the multicultural American abolitionist movement as an evolution of racial concepts and related their significance to Black Lives Matter today.

According to Alcenat, the Haitian Revolution’s legacy recognized the concepts of race only historically without giving any validity to the white supremacist lens. He also added that the American abolitionist movement was the first mass multicultural, multiracial movement to indicate a new concept of what it means to be an American “regardless of your shades of color” and related this to the Black Lives Matter movement and its significance in defining freedom, Americanism and inclusion.

“The point here is those who are the most dead, denigrated, the most despised, the most oppressed, those are the people who are to define what freedom is,” he said. “Once those people get to define freedom, that’s when freedom really becomes universal.”

The talk yielded nearly 80 people in attendance and concluded with a conversation between Alcenat and Zapata about what the future holds.

The talk yielded nearly 80 people in attendance and concluded with a conversation between Alcenat and Zapata about what the future holds.

“I’m still trying to make sense of this post-George Floyd moment,” Alcenat said. “I am still grappling with these legacies of Juneteenth and of the Haitian Revolution and what we now do in the post-George Floyd moment.”