Misguided Criticism on Race Relations in “The Help”

Upon Closer Look, the Controversy Surrounding “The Help” Amounted to Hyper-Sensitivity

September 21, 2011

“I refuse to see ‘The Help,’” one of my co-workers vehemently told me. He continued, “It’s an insult to black people and it suggests that black stories are only valid when told by a white narrator!”

Though startled by the fervor in his voice, I could empathize with his frustration. It’s no secret that blacks have struggled for accurate representation in film and television only to consistently be portrayed in stereotypical roles that are generally subordinate to white counterparts.

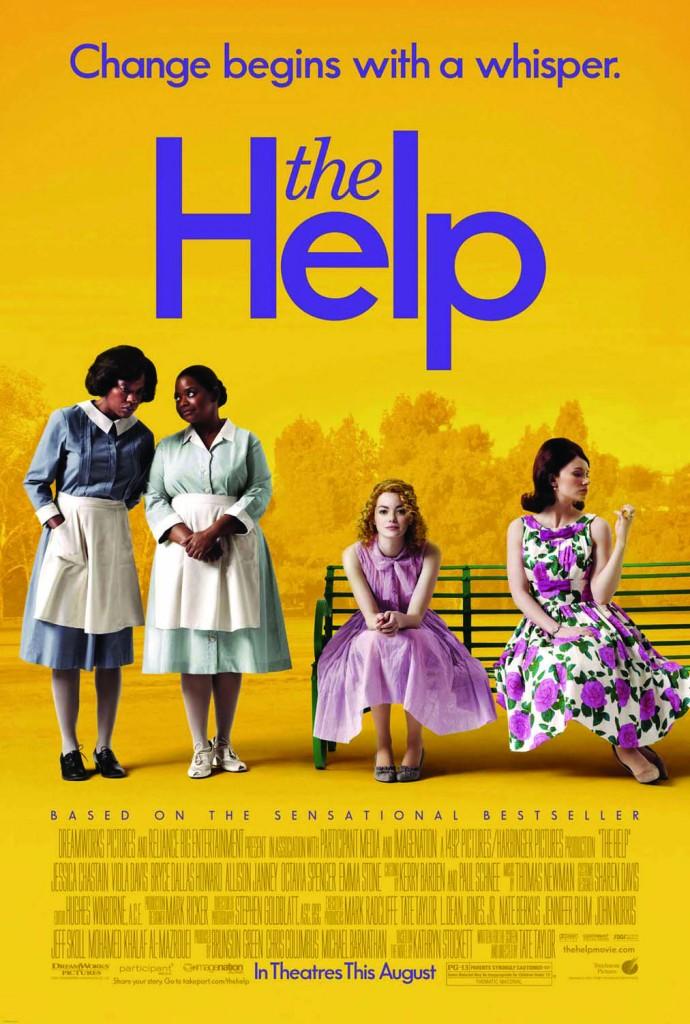

With its frank title and the imagery of black maids Aibileen Clark (Viola Davis) and Minny Jackson (Octavia Spencer) doting on white Southern belles Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan (Emma Stone) and Hilly Holbrook (Bryce Dallas Howard), “The Help’s” ubiquitous movie poster captured the long-held notion of black inferiority. Sometimes I’d catch myself staring at it. The bold reflection of racial segregation suggested that I, as a black woman, should be offended, but I only became intrigued.

Viewers across the country, white and black, raved about how inspiring the film is while toting around a copy of the book by Kathryn Stockett. A story of a white female writer who joins forces with black maids, “The Help” recently held the number one spot at the box office for a record of 25 days and surpassed the $100 million mark.

Not surprisingly, while garnering such success, the film stirred up quite the controversy.

Some black intellectuals were up at arms. Tariq Elite, author and radio personality, dubbed the film as “fake liberalism.” The Association of Black Women Historians (ABWH) issued a public letter saying, “Despite efforts to market the book and the film as a progressive story of triumph over racial injustice, ‘The Help’ distorts, ignores and trivializes the experiences of black domestic workers.”

The letter goes on to argue that the southern dialects and poor vernacular of black characters in “The Help” were grossly exaggerated and that the issues of sexual harassment, the plight of civil rights activists and attacks from white supremacy groups like the Ku Klux Klan were glossed over.

My question to these critics is, have you read the book? I ask because it appears that many of them have not. Many of their criticisms of “The Help” glossing over sexual harassment, violence against civil rights activists and hate crimes were addressed in the novel through various firsthand accounts of rape from black workers, the inclusion of civil rights activist Medgar Evers’ assassination within the plot and the murder of Aibileen’s son by white supremacists.

Elite was completely right when he said, “This movie is about a white girl coming of age and the magic mammies who inspired her to do so.” After shortening the story to entertain a wide array of audiences, the film version of “The Help” lost the original plot’s sophistication.

The result resembled your average feel-good movie consisting of banter, harmless pranks, and the occasional tear-jerking scene fluffed with vintage fashion and southern drawls. The relationships between the whites and blacks are rigidly constructed and many of the characters’ personal issues are either omitted or reduced to trivial parts of the plot. All of the factors that gave the story its complexity are taken out, making “The Help” one of many films about white saviors and their grateful, helpless black dependents. Elite sums it up beautifully as “Disney bullshit.”

However, had I not read the book before seeing the film, I would have perceived Stockett’s story as ABWH and Elite had described it: a light-hearted film that demeans black oppression, pushing a white character of secondary importance to the forefront. I would not have understood that in the original book, the playing field between the white and black characters is leveled by each individual’s anxieties, imperfections and pressures to conform to society’s unwritten laws in race relations.

Yes, the premise of the story is of an upper class white woman, Skeeter, writing about the lives of black domestic workers. But Stockett makes a point to tell the story from the perspectives of white and black characters, exposing problems faced by both races and debunking the concept of privilege. Furthermore, the ethical question of whether Skeeter has the right to tell these stories as a white narrator is frequently raised in the book.

Also, the consequences of writing the book, specifically the threat of potential hate crimes, are shared between both races. While Skeeter is slowly shunned by her town for supporting the civil rights cause, she, Aibileen, Minny and other domestic workers live in fear of the violence that could ensue once their identities within the book are revealed to their white employers.

Critics of “The Help” were so thrown off by its brazen statement on race that they missed the point of the story. “The Help” seeks to show women working together in spite of their fears and racial differences to celebrate the lives of an underappreciated class. The film struggles to do that, but the book succeeds. It’s not fair to attack Stockett for Tate Taylor’s poor film adaptation of her original work.

Though flawed in historical accuracy, this book has generated a discussion on the oppression of black domestic workers that otherwise would not have happened. Critics, was there really anything to complain about?