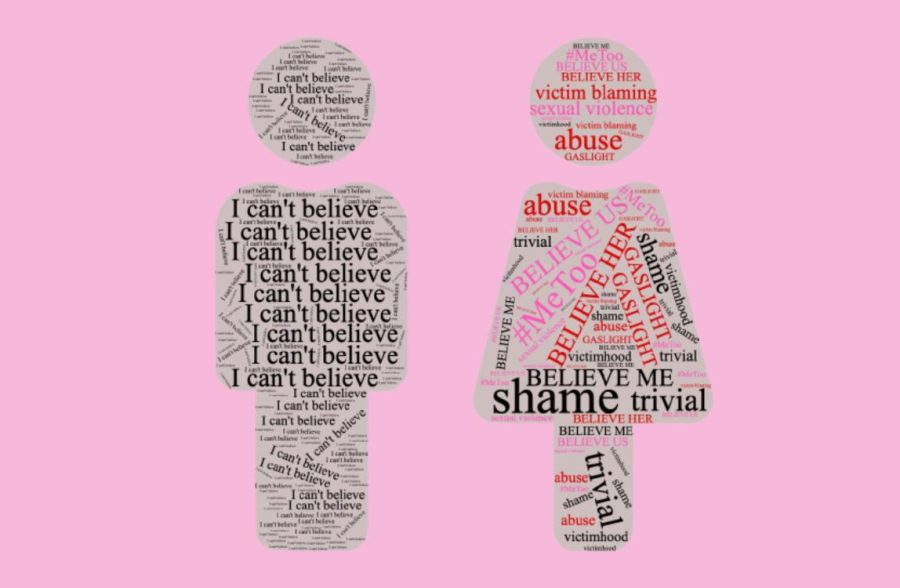

Remove ‘I Can’t Believe’ From Sexual Assault Conversations

#MeToo created a space to talk about the harsh realities of being a woman in a world where sexual violence is rampant — now it’s time to reflect on those conversations

There is a balance between experiencing the consequences of trauma and not letting those consequences define you.

February 17, 2022

Content warning: sexual assault.

“I can’t believe any man would do that.”

“I can’t believe that you were treated that way.”

“I can’t believe”: That phrase holds more power than some think.

In the years after the #MeToo movement, women have begun to bravely step into the public eye and share their experiences with sexual harassment and assault more frequently. In an effort to reclaim their lives, narrative and power, women have risked their careers, safety and mental well-being to spread awareness about these daily tribulations and, in many cases, the subsequent severe and long-term trauma.

I have begun to talk about my experiences with assault and harassment, particularly with my male friends. Almost every time, I am met with sympathy; but even more with shock. And, of course, the resulting response: “I can’t believe…”

Why respond with “I can’t believe”?

While I am grateful that my male friends gave me the space and safety to recount these experiences, the shock I have been met with has always confused me. If sexual harassment is so common, why am I met with wide eyes and gasps? If experiences like this happen to women every day, why is it so unbelievable?

This is not to say that women don’t react with the “I can’t believe” mentality. Their responses, however, tend to be more varied. Rather than shock, I am often met with similar stories of sexual assault. So, once again, I raise the question: Why respond with “I can’t believe”?

This phrase, though well-intentioned, is a low-grade form of gaslighting. The term “gaslighting,” too, has entered the conversation surrounding sexual and emotional abuse against women. I have even heard my male friends apply this phrase to their own experiences of manipulation and invalidation. I applaud them for it, but it is time that the phrase is applied and reflected upon on a different level, beginning with the vocabulary used surrounding these conversations.

The women who came forward prior to, during and after the #MeToo movement were gaslit regarding their experiences.

The term gaslighting first gained popularity after the premiere of the 1938 play “Gaslight,” which followed the life of a woman who slowly went insane at the hands of her manipulative husband. The term then regained popularity during the 1970s and 1980s in academic journals, particularly those studying gender dynamics.

Then, with the rise of the #MeToo movement, the phrase sprung to the forefront of conversation as women recounted situations in which their reports of sexual abuse were dismissed. The phrase became so popular that it was even named one of Oxford Dictionary’s 2018 words of the year.

In short, gaslighting is not a new phenomenon. Abuse is nothing new. What is new is the growing and popularized vocabulary surrounding these conversations.

The women who came forward prior to, during and after the #MeToo movement were gaslit regarding their experiences, despite successful efforts to shed light on perpetrators of sexual assault. Only about one in three female victims come forward to report cases of assault. The number of men who come forward is even lower: Only 13% of male victims of sexual assault file a report.

This is a result of the trivialization of victims’ experiences and feelings, trapping them in their own personal hell of shame, anger and even internalized gaslighting. I have caught myself trivializing my own experiences, asking myself questions like “What if I wasn’t actually assaulted?” or “Am I overreacting?” and even, “Is my reaction normal?”

Sexual violence should not be normal. Unfortunately, it has been normalized, and the practice is only beginning to be reversed. There is no “right” or “wrong” way to respond to and process these traumatic experiences because they should inherently be abnormal.

Why must I regulate my own behavior around men to avoid danger?

The conversation around victimhood must be considered in relation to the term gaslighting. Women are constantly warned against developing a victim mentality, a warning that brings forth its own set of dangers. Though often unintentional, it opens the door for “victim-blaming,” another phrase that has gained popularity since the rise of the #MeToo movement.

This phenomenon is present in phrases such as, “You put yourself in that position” or “You have to be more careful,” which even I have been told. Why must I regulate my own behavior around men to avoid danger? Why can’t men just learn not to be dangerous?

There is power in acknowledging victimhood. Being candid about the effects of trauma is the first step toward healing from it, and there is a balance between experiencing the consequences of trauma and not letting those consequences define you.

When the phrase “I can’t believe” is brought into a conversation surrounding sexual assault, it encourages a mindset of disbelief.

The development of better defining and encapsulating the daily experiences that women face is a huge step forward. The fact that this vocabulary is being popularized draws even more attention to these issues. The next step is to continue the development of this new set of vocabulary through sustained conversation, no matter how uncomfortable or emotional it may be.

Vocabulary shapes mindset. When the phrase “I can’t believe” is brought into a conversation surrounding sexual assault, it encourages a mindset of disbelief. It’s time to strike that phrase from our collective vocabulary.

Believe me. Believe her. Believe us.