Pandemic Exposes Inequities in Health Care System

Historically marginalized groups forced to weather faltering health coverage coupled with job insecurity

February 4, 2022

On March 26, 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. stated, “Of all forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.” Though it was said at the Convention of the Medical Committee for Human Rights in Chicago nearly six decades ago, it remains relevant today with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic has highlighted social and racial injustice and inequity in public health, putting racial and ethnic minority groups at a higher risk of becoming ill and dying from COVID-19.

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.” These conditions are divided into five categories, which include economic stability, neighborhood/built environment, education access/quality, social/community context and health care access/quality.

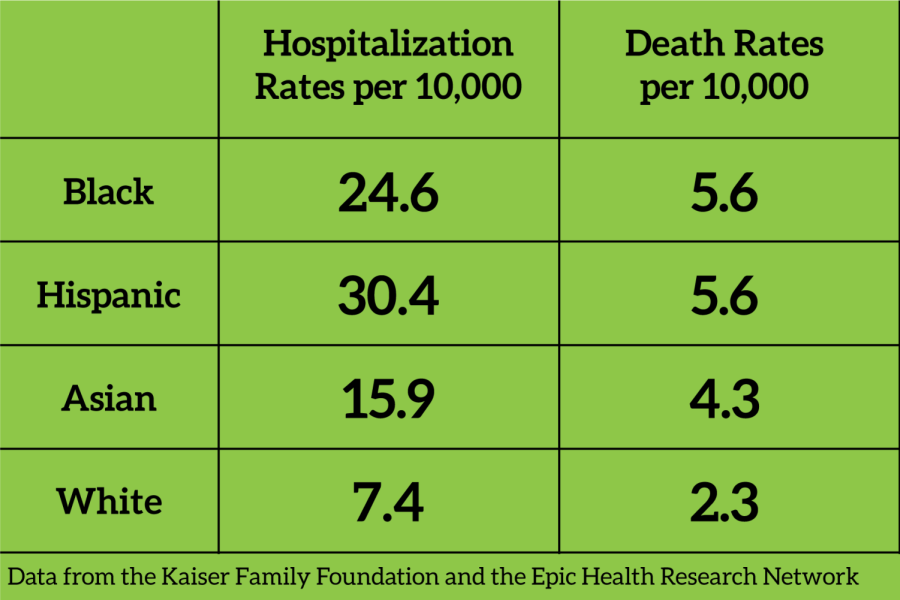

When compared to white people, Black, Hispanic and Asian people have significantly higher rates of infection, hospitalization and death from COVID-19.

These circumstances contribute to societal stratification and thus exacerbate health disparities among various groups of people based on social and economic class, gender, and ethnicity. SDOH are a root cause of many of the current major societal health issues, such as obesity, heart disease, diabetes and depression.

Underserved populations and people of color usually experience higher levels of stress because of poor health, lack of education and low-income jobs that put a constraint on their lives. These conditions distance them from health care, nutritious food, physical activity and other healthy coping mechanisms.

Disproportionate Effect of COVID-19

When compared to white people, Black, Hispanic and Asian people have significantly higher rates of infection, hospitalization and death from COVID-19. According to a 2021 study conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Epic Health Research Network, “the hospitalization rates and death rates per 10,000, respectively, were 24.6 and 5.6 for Black patients, 30.4 and 5.6 for Hispanic patients, 15.9 and 4.3 for Asian patients, and 7.4 and 2.3 for White patients.”

Because people belonging to historically marginalized groups typically work in “essential fields,” many of these individuals were unable to work remotely during the worldwide lockdown. Jobs such as transit workers, grocery store clerks, nursing aides, construction workers, household workers and sanitation workers were all still active when the streets were barren.

These workers were not protected and feared exposing their families to COVID-19 as they lived in crowded conditions or multigenerational households.

Mistrust in the system might lead vulnerable populations to delay seeking care or medical attention. About 1.6 million Hispanic families have lost access to employer-sponsored health insurance since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, making up nearly half of those who lost coverage. Furthermore, immigrant and undocumented populations are less likely to access the health care system due to fears of deportation and legal issues.

Disparities in disease outcomes due to race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status is not something new in the United States. COVID-19 has stressed the urgency of these disparities and made social conditions worse for many Black, Hispanic and Indigenous people in the United States. However, these inequities are not unchangeable.

John Walton • Feb 8, 2022 at 10:42 pm

Did you “norm” the statistics for indicators of likely and inherited morbidity, i.e. diabetes, obesity, cancer, hypertension, renal issues etc.

Not a very thorough analysis in my view. The data above is readily available from the NYState Department of Health.