Acceptance of Self: Learning to Be Muslim in a Post-9/11 World

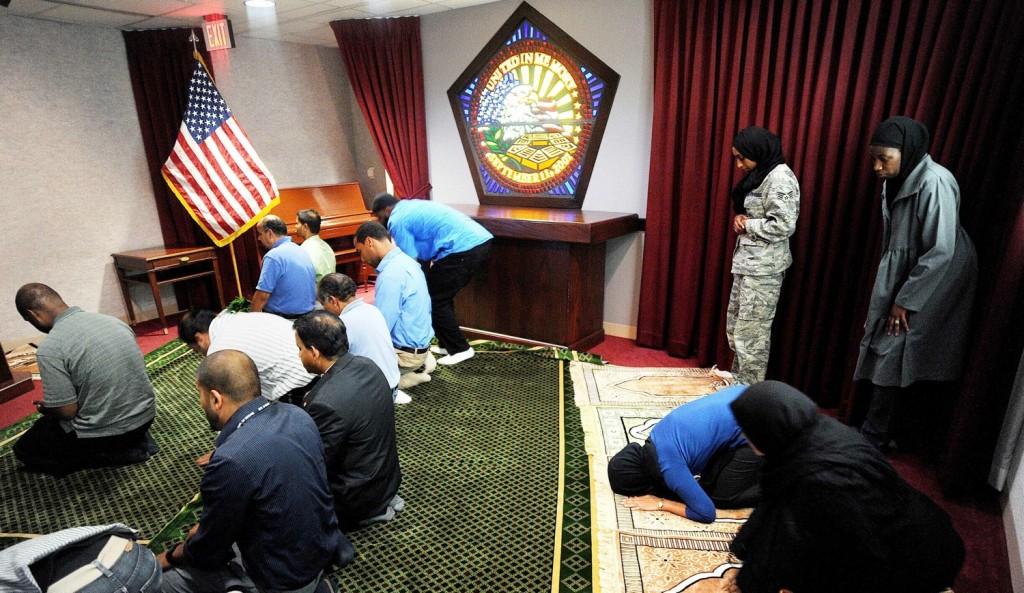

Olivier Douliery

The Pentagon is one place where there’s no discussion of whether it’s appropriate for Muslims to pray near the site of the 9/11 attacks. Every Friday, Muslims gather to worship in a chapel built in the very space where a hijacked jetliner plunged into the Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001.(Olivier Douliery/Abaca Press/MCT)

September 11, 2011

I do not know any victims, survivors, servicemen or families who lost loved ones on Sept. 11. However, I do know what it is like to be Muslim and Middle Eastern in post-9/11 America.

When I focus on the memory of Sept. 11, I mourn the nearly 3,000 people who died in the attacks. I mourn the death of patriotic soldiers who immediately joined the fight against terrorism in our country’s subsequent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In addition, I cry for the Iraqi and Afghani civilian casualties from these past 10 years. I cry for the victims of raging American Islamophobia. I cry for the innocent Guantanamo bay detainees. Lastly, I cry for and mourn the destabilizing of the Middle East as a result of America’s war on terrorism.

The morning of Sept. 11, I was sitting in my sixth grade history class when our principal went on the loudspeaker to announce the news. That afternoon the news kept replaying the attacks. That night they showed film reels of some Middle Eastern people burning the American flag in celebration. My mother was Middle Eastern and she was weeping in front of the television that day, rashes broken out on her arms. She’s of the same regional and religious identity of the attackers, but she is not like those radicals on the television.

When I went back to history class the next day, the atmosphere was raw. Our feelings of vulnerability and of patriotism were fresh and crude like newly-opened wounds. For me every day afterwards there were also gnawing questionings of who am I and how am I different from those attackers? I am Muslim and Middle Eastern, but I’m still not from a society or a family like the attackers. I felt like I was being pushed into an identity crisis.

I grew up in a small Catholic town in Connecticut. I attended a public school system where I was one of few (if not the only) Muslim females. None of my friends knew about the country Iran, the place from which my parents emigrated. The majority of my middle school peers were not even educated about the Middle East and just assumed that my darker skin color meant that I was Indian. As an American teen, I just wanted to fit in. In order to do so, I superficially detached myself from my Middle Eastern and Muslim background. I would be embarrassed by the kebab that my mom put in my brown bag for lunch. I was also ashamed of my mom’s long black hair and naturally tanned skin.

After Sept. 11, I was forced to grapple with my identity as a Middle Eastern and Muslim American. My mother dyed her hair blonde in order to be less conspicuously foreign. My brother drew a picture of superman flying off a building and his teacher pulled him aside for “promoting terrorism.” My father was called a “towel head” by road-raged drivers on the street. When my family returned to America after a trip to Iran, we avoided JFK Airport because they made us open all eight of our suitcase bags and thoroughly searched through them.

I was forced to explore my background, because in post-9/11 America, I was confronted by discrimination and ignorance. The summer of 2002, my mother took me to Iran. “Do not let terrorism stop you from seeing your family,” she said. I was understandably hesitant about boarding a plane that would stop at a country right next to Afghanistan, where the United States had just started a war. I walked off the plane and entered the dictatorship of the Islamic Republic of Iran where you are forced to obey Shari’a laws and wear hijab in public. When I left I was well aware of how my background and beliefs were different from the Sept. 11 attackers.

My Iranian family instilled a pride in me for my background. I was proud to be from a community of people who are keenly aware of the negatives of radical religion. I was proud to be from a community of Muslims who were not narrow-minded and austere. I was proud to be from a country with an ancient history and a rich culture. I was also proud to be the daughter of a woman who cherishes her country of birth but appreciates America for presenting her with opportunities for positive change that we could not have found anywhere else.

Today, I try to defy stereotypes about Middle Eastern people and Muslims. I’m also passionate about educating the average American about Islam, Middle Eastern history and American foreign policy. I’m zealous about showing the points of view of different people and not just radical terrorists. After remembering the tragic events that took place on Sept. 11, I also look at how lucky I am now to be educated about these issues.