The Met Gala, Explained

How a small fundraising event became the most exclusive party in pop culture

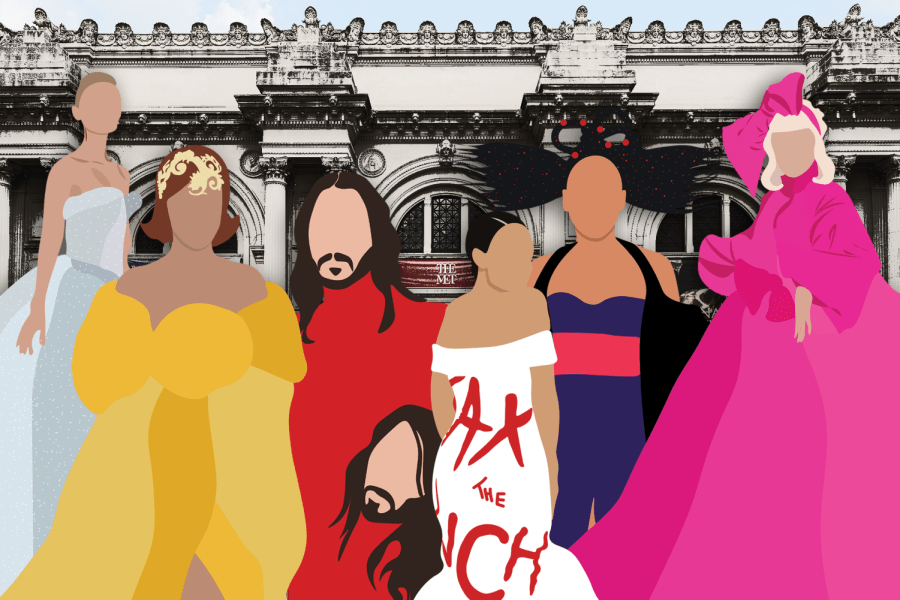

Attendees of this year’s Met Gala included fashion icons and celebrities.

September 23, 2021

Every first Monday of May, the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art are populated by the most important people in fashion, culture, sports and politics. Across Fifth Avenue, passersby crane their necks and phones to get a glimpse of their favorite celebrities. But it wasn’t always this way.

Humble Beginnings

The story of the Costume Institute Gala — known best as “the Met Gala” — begins with the history of the institute itself. As theater in America reached its peak in the 1920s, producer Irene Lewisohn and stage designer Aline Bernstein saw a need for an archive of costumes from which costume designers could draw inspiration. The collection grew to over 8,000 pieces when it officially became part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1946. Now known as the Costume Institute, the general public could also see the “clothes as beauty, as part of the embellishment of life,” according to Vogue.

The Met Gala was the brainchild of publicist Eleanor Lambert, who also founded New York Fashion Week and the International Best-Dressed List. The first fundraising benefit took place in 1948, coinciding with the Institute’s first exhibit. Branded “The Party of the Year,” it was attended by everyone in Lambert’s “Rolodex of the rich and famous” and the most important names in the fashion industry. After the inaugural gala, the event became the most important event of the year for New York’s high society.

The Vreeland Years

Following her termination as editor-in-chief of Vogue, Diana Vreeland brought her dynamic and extravagant sensibilities to the Costume Institute and its annual fundraising benefit; she is responsible for the event that we recognize today. Vreeland introduced themes that coincided with the Institute’s exhibit for that year. Themes ranged from honoring fashion designers (1973’s “The World of Balenciaga”) to reminiscing on iconic moments in fashion (1974’s “Romantic and Glamorous Hollywood Design”).

With Vreeland at the helm, the Met Gala also became a means of advertising the exhibitions at the Institute. Previous years saw the Met Gala held at various locations around Manhattan, such as the Rainbow Room and the Waldorf Astoria, but Vreeland made the move to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was during her tenure that the Gala first began harnessing the power of celebrity by inviting the most glamorous women of the time — notably former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis — to co-chair the event, and inviting stars like Diana Ross, Elton John and Cher to the societal event.

Wintour brought her revolutionary editorial sensibilities to the Institute and its Gala like Vreeland before her.

The Interim of Pat Buckley and the Dominance of Anna Wintour

After Vreeland’s death in 1989, socialite and longtime co-chair Pat Buckley briefly took the reins and continued to feature the best dressed of both New York high society and Hollywood on the red carpet. Buckley began to sell “excessively priced” afterparty tickets for dessert and dancing, and ticket holders flocked to the museum to see the opulently dressed dinner guests.

By the time Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour took over as chairwoman in 1995, such tickets cost $1,000. The price tag to attend has only skyrocketed since. In 2019, tickets cost $35,000 per person. Fashion houses and brands spend up to $300,000 on tables and invite guests — but Wintour gets the final say on the guest list.

Wintour brought her revolutionary editorial sensibilities to the Institute and its Gala like Vreeland before her. In a time when celebrity magazine covers were taboo for respectable publications like Vogue, she took a risk and had celebrities and fashion models grace its cover. She treated the Gala’s guestlist likewise, blurring the line between celebrities and high society.

Changes to the Gala in Wintour’s era do not end there. The event famous for occurring on the first Monday of May was traditionally held in December. Following the death of the Costume Institute’s curator Richard Martin in 1999, the Gala was moved to the spring, and it simply stuck. It was only delayed to the fall this year because of the pandemic.

Designers take the opportunity to showcase their best work, meaning that the biggest stars are wearing incredibly intricate, creative and often outrageous outfits.

The Met Gala as a Pop Culture Phenomenon

The mystique of the Met Gala has grown with the age of social media, captivating fashion lovers and pop culture enthusiasts of the internet. Although it is a fundraiser for The Met, the lavish party is almost solely for the public eye. Designers take the opportunity to showcase their best work, meaning that the biggest stars are wearing incredibly intricate, creative and often outrageous outfits. This is the perfect recipe for internet virality.

From Claire Danes’ glowing Zac Posen gown in 2016 to Jared Leto’s replica of his own head in 2019, the ridiculous extravagance of the world’s ultra-famous has inspired mockery and awe alike, demonstrated by the memeification of photoshopping Rihanna’s Guo Pei robe into an omelet.

The 2018 Gala, “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion in the Catholic Imagination,” was the height of the online craze. It inspired a wave of posts of what people would have worn had they been among the select few invitees. The exhibit became The Met’s most successful to date, selling 1.3 million tickets and beating the previous record.

Interest remains high with tens of thousands viewing the livestream of its comeback this year.

The theme, “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion,” was a call for national unity and pride amid the COVID-19 pandemic and ever-deepening political rifts.

The 2021 Met Gala

The Met Gala on Sept. 13 marked the return of this extravagant event after cancellations due to the pandemic in both May 2020 and May 2021.

This year’s Met Gala was co-chaired by Oscar-nominated actor Timothée Chalamet, Grammy-award-winning singer Billie Eilish, National Youth Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman and four-time Grand Slam singles tennis champion Naomi Osaka.

The theme, “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion,” was a call for national unity and pride amid the COVID-19 pandemic and ever-deepening political rifts. Many attendees expressed apprehension about celebrating America. Some, like Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, used the highly publicized event to make a political statement. Others chose to pay homage to iconic American eras, with plenty of glittering Old Hollywood-inspired gowns and tuxedos, and sleek disco looks calling back to Cher and Diana Ross.

Such an elite and expensive event is not without controversy. Nicki Minaj, a usual guest, was absent because she refused to comply with the Gala’s mandatory vaccine requirement. Additionally, protesters gathered outside the museum criticizing the opulence of the event during a time of great economic hardship and were violently suppressed by the NYPD while Vogue livestreamed the red carpet. Despite the unrest, the celebration and media fanfare went on.

While not every attendee forked over $35,000 for a ticket to fashion’s most exclusive party, guests — like AOC — garnered criticism for attending because of the Gala’s grandeur. Yet there are some inclusive strides being made inside the white tent on the steps.

This year’s Met Gala was attended by Quannah Chasinghorse, an Indigenous model and land protector, who saw that it was important to “represent and bring authentic and true American culture to this year’s theme.” Likewise, British racing legend Lewis Hamilton paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to buy a table and populate it with young Black designers, making space for them at an event whose red carpet is chiefly composed of old, white fashion houses.

Perhaps in future years, the party that was once the highlight of the societal calendar will be a platform for highlighting the wide array of societal issues.