One Shot, Two Shot: The Differences Between the Two Vaccine Types

Why some vaccines require two shots instead of just one

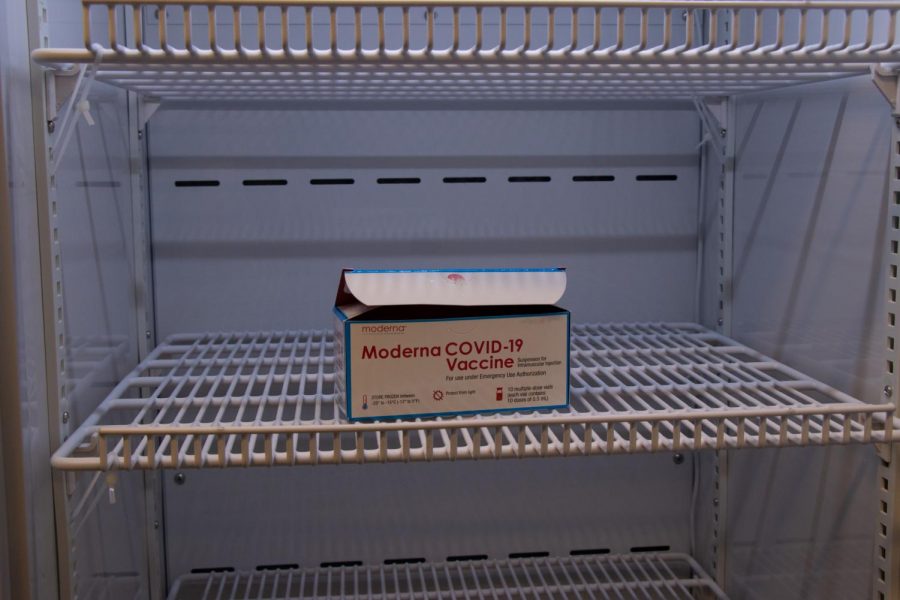

Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are mRNA vaccines and require a two-shot regimen for full vaccination.

May 2, 2021

For all the talk about vaccines, there exists an important question that many don’t understand the science behind: What’s the difference between a one-shot and two-shot vaccine? Thankfully, the answer for why some vaccines involve an additional jab is far simpler than you might think.

According to Patricio Meneses, who holds a doctorate in neuroscience and is the chair of the biological sciences department at Rose Hill, a two-dose vaccine is meant to better acclimate your body’s two main defenses of the immune system: B-cells, which create antibodies that detect and bind to a virus’ protein receptors and prevent it from infecting other cells, and T-cells, which absorb and destroy viruses themselves.

“Within the first three to five days of exposure, the process is only still beginning, when your B-cells are still creating antibodies,” Meneses explained. “As you begin to go through this process, you make more and more cells that target the antigen itself. Eventually, your body has produced enough antibodies and T-cells to fight and eliminate the virus.”

“You can never get infected with coronavirus via vaccine; you are only getting that spike protein.”Patricio Meneses, chair of the biological sciences department at Fordham College at Rose Hill

Both Pfizer and Moderna are mRNA vaccines. As the name suggests, these vaccines contain segments of the novel coronavirus’s mRNA, which can only produce certain proteins found in the virus rather than fully infecting a host. “The way the vaccine works, you can’t make more mRNA; you can only make more mRNA if you actually have the virus,” Meneses said. The mRNA itself is coded by our cells’ ribosomes, which in turn produce copies of the novel coronavirus’s protein receptor, the ubiquitous “spikes” commonly seen on depictions of the coronavirus.

Meneses stated that the protein receptor, ACE-2, acts as an antigen, or a toxin that the immune system recognizes and produces antibodies to fight against. The protein receptor is then sensed by the immune system, which responds by producing antibodies meant to latch onto the ACE-2 receptors and prevent them from attaching to and infecting human cells.

“You can never get infected with coronavirus via vaccine; you are only getting that spike protein,” Meneses clarified. “Your body is now making antibodies that can recognize this protein when they see it, and attach to it, thus preventing infection.”

Each dose given in a two-shot vaccine is actually identical to the other. In other words, you’re receiving the exact same vaccine several weeks later. The reason for dividing them into two doses is to better acclimate the host to these antigens. When your body detects any antigens, the immune response is triggered, which includes the telltale symptoms of lethargy, muscle aches, fever and nausea. These side effects of the vaccine are not from the coronavirus itself, but rather your body’s natural response to foreign invaders.

This is why two-shot vaccines are administered, as they expose our bodies to the novel coronavirus’s antigens more gradually, allowing for the immune system to build the respective antibodies. This is how immunization works, as an inoculated individual who is exposed to the coronavirus already has the antibodies necessary to stop the virus from infecting the body.

So why space the doses out? According to Meneses, “the two doses back-to-back may get you a ton of memory cells.” Memory cells house previous antibodies your body has utilized, acting as an archive of sorts. The higher quantity of memory cells activated by an immediate second dose may unnecessarily trigger your immune response. Additionally, Meneses stated that “over a three-to-four week period the chances of getting enough memory cells is actually higher,” thus better ensuring your immunity while avoiding the worst of the side effects.

Another reason behind two-shot vaccines is also one of logistics and availability, Meneses stated. “When it comes to delivery of the drug it really depends on if you can get a second dose at all,” Meneses said.

Many countries without the means to produce their own vaccines receive exported one-shot vaccines, such as the one-shot Johnson & Johnson or AstraZeneca. While this has created a dilemma of rich countries dumping supposedly inferior vaccines on poorer ones, the reality is that any dose of any vaccine that is currently approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can be trusted.

“From our perspective,” Meneses concluded, “they’re both just as good.”