My Childhood Under Military Dictatorship in Myanmar

The fight for democracy is not over

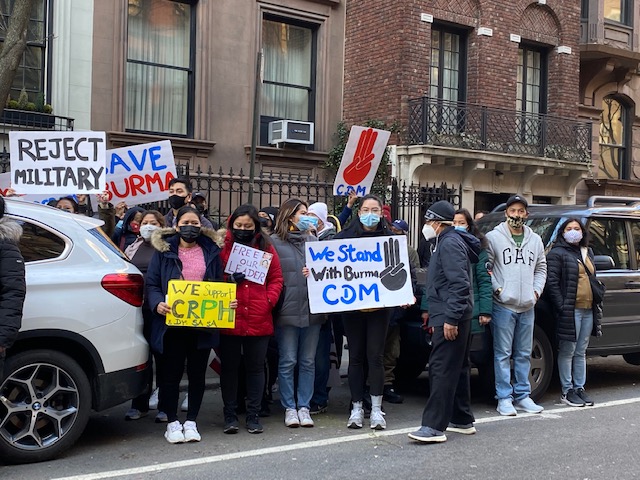

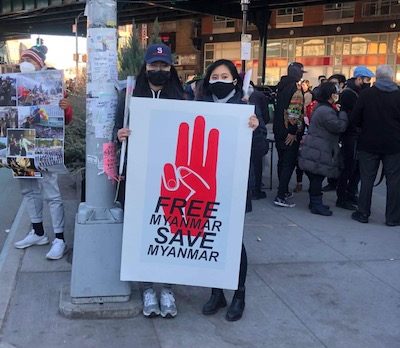

COURTESY OF HAN OO

Protests have sprang up across the world, including in New York, in support of democracy in Myanmar. Oo has attended three since the coup.

March 19, 2021

“Why are monks protesting in the streets?” I asked my papa when I was eight years old. The streets were filled with monks with their saffron-colored robes marching down major streets in the city. During the 2007 North Indian Ocean cyclone season, Myanmar was hit economically as well as physically. In the aftermath, Buddhist monks could not stand to watch the people of Myanmar suffering, so they went to the streets to protest. They said that the government had not taken any action to help the people.

The 2007-08 Saffron Revolution was a peaceful protest led by Buddhist monks against the Burmese military dictatorship. I was only eight, sitting on the shoulders of my papa, but I protested alongside them.

As a daughter of an asylum seeker living in the United States, I was completely shocked by the military coup that took place on Feb. 1, 2021. I was born in Yangon, Myanmar. Until I immigrated to the United States at 10, I grew up under a military dictatorship. For the first 10 years of my life, I was only exposed to military propaganda.

As a child, the military brainwashed me into believing that the non-Bamar ethnic groups living in Myanmar were troublemakers.

It was not until I went through schooling in the United States that I learned about democracy and individual rights. Hearing about the American Constitution in my AP United States History class, I dreamt about a Burmese version of democracy for my people back at home, imagining beautiful scriptures filled with pages and pages of the Burmese language.

It took me eight years to become an American citizen. Before I became a citizen, I could not go back to Myanmar because it was not safe for me as a daughter of a political activist. In 2017, I finally went back home and was able to see my family for the first time in seven years.

When I was there at the end of 2019, I passed by Aung San Suu Kyi’s home. Aung San Suu Kyi is the daughter of a general who helped Myanmar gain independence from Great Britain. As a result, she was put on house arrest. I remember when I was attending school, her home used to be lined with barricades. Now, the barricades were gone. Myanmar was marching toward democracy as the 2020 November election approached.

The skyline of Yangon was slowly filling up as other nations invested in Myanmar’s infrastructure. I saw new hope for the future of Myanmar. Myanmar citizens, both domestic and international, went out to the polling sites and embassies to vote in the November 2020 election. The National League for Democracy (NLD) party won the election.

On Feb. 1, 2021, the day the newly elected government officials were supposed to be sworn in, a coup occurred. The coup happened early in the morning when the entirety of Myanmar was asleep. All the communication channels had been cut off except for the military-owned channels. The internet, phones and even news channels were all shut down by the military.

As the military coup was taking place, I finally understood everything the Burmese refugees were fighting for.

Myanmar is a unique country made up of more than 135 ethnic groups. However, not all of them have equal rights. As a child, the military brainwashed me into believing that the non-Bamar ethnic groups living in Myanmar were troublemakers.

It was not until I left government-funded school and came to the United States that I learned the sad reality. When I first learned the word “refugee” in school, I was taken aback. As the military coup was taking place, I finally understood everything the Burmese refugees were fighting for.

As a university student, I am tired. I am tired of being brainwashed by the military for the first 10 years of my childhood. I am tired of hearing about my parents and their university lives during the 8/8/88 Uprising. I am tired of listening to my grandfather and hearing what the military did to our independence after his father fought along with General Aung San for the freedom of Myanmar.

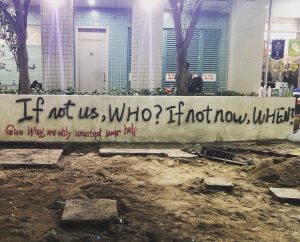

However, my hope prevails. General Aung San paved a path for Myanmar and its democracy when Myanmar was freed from Great Britain. As the Civil Disobedience Movement gains momentum in Myanmar, my hope is that this generation and those to come will join and fight for democracy in Myanmar.