Night Life in Black & White

July 23, 2011

Published: May 5, 2011

It is difficult to imagine the time—and yes, there was time—when night photography required more than a disposable camera or iPhone. As we move through time, and new technologies continue to simplify our lives, the artistic ingenuity and persistence that went into early night photography is quickly being forgotten. Dimly lit bars and dark streets no longer hinder our ability to capture life after sunset. Turn on the flash, and you are good to go.

“Night Vision: Photography After Dark,” on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, revisits that distant time, exploring the evolutionary process of taking photos at night. The exhibit, which runs through Sept. 18 in the Howard Gilman Gallery, features 40 black-and-white images from the 1890s to the present, from early photography pioneers such as Alfred Stieglitz to modern artists like Stephen Tourlentes.

“Night photography encompasses a large portion of 20th century photography. Both thematically and stylistically, the images in the gallery speak to each other,” Met curator Mia Fineman said. “They are related in their desire to capture the world in darkness. Something, at least in the early years, that has never been done.”

At the turn of the 20th century, night photography came into its own, asserting itself as a prominent and exciting artistic genre. The ability to accurately capture the quality and essence of the night had fascinated and eluded artists for years. This all changed with the introduction of the gelatin dry-plate process, which reduced exposure times and simplified the work of photographers, allowing the genre to expand.

Stieglitz, instrumental in this expansion, and husband of Georgia O’Keefe, began experimenting with night photography in 1897. In works such as “Reflections: Night, New York” (1897) and “An Icy Night” (1898), Stieglitz turned his camera to the streets of New York City, capturing the feeling of being seemingly alone in a city full of millions. While the images are a reflection of Stieglitz’s personal feelings of isolation, they are more striking when taken from a modern perspective, giving us a brief glimpse into a world that seems eerily familiar, and at the same time, incredibly distant.

In the 1930s, as modern cities grew and technological developments flourished, the photographer, Brassaï began capturing Paris at night. Undoubtedly influenced by the work of Stieglitz, Brassaï chronicled nearly every aspect of Paris nightlife, from the seedier sides of town to the world of high society. In “Morris Column in the Fog,” Brassaï creates a dreamy cityscape, intensified by the heavy fog of nighttime Paris.

Brassaï’s work influenced a large number of photographers, not only in content, but in style as well. Brassaï preferred to shoot on rainy and foggy nights, writing once, “It is necessary to photograph certain subjects in the rain, since it is the rain that make them photogenic.” This aesthetic quality became a trademark of night photography, as artists around the world began capturing the night in a similar fashion.

Bill Brandt, a prominent English photographer and photojournalist, specialized in photographing London during the German Blitzkrieg in World War II. London, which was undergoing a self-imposed blackout to make themselves less vulnerable to German bombers, appears dark and mysterious in most of Brandt’s wartime work. His photo, “London by Moonlight: St. Paul’s” (1943), shows a distant cathedral, black and silhouetted, standing alone among the decrepit ruins of a war-torn London.

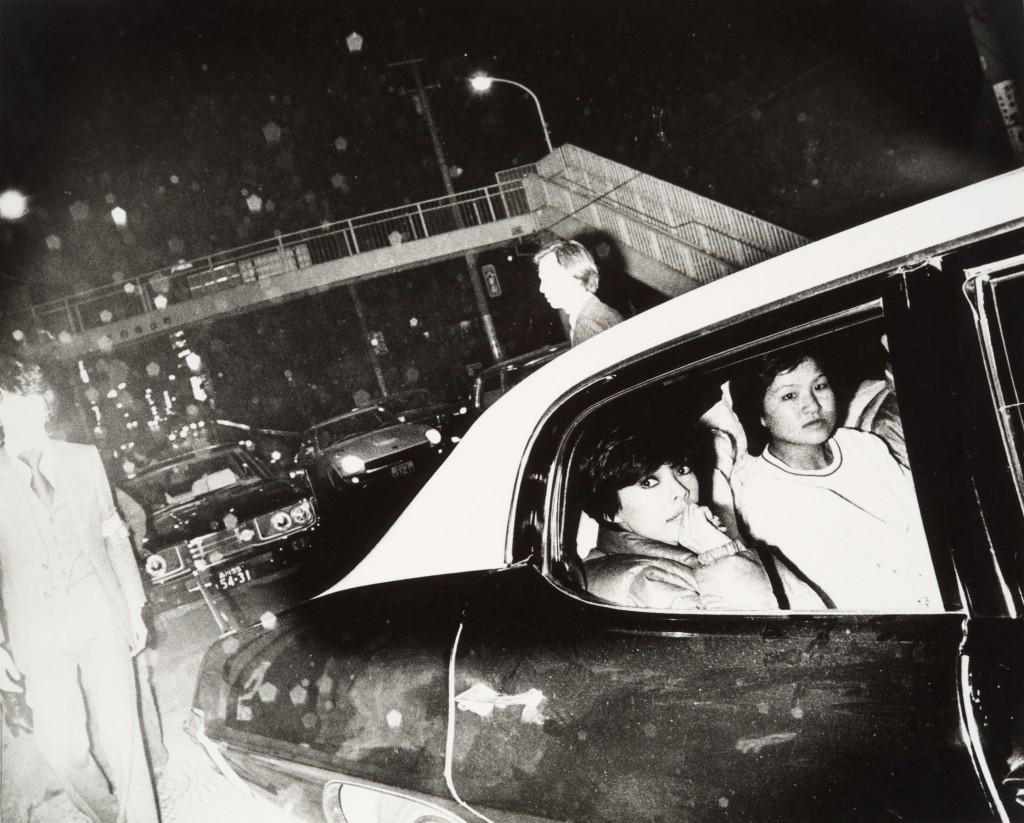

More recently, artists such as Kohei Yoshiyuki and David Deutsch have begun using more experimental techniques to explore different corners of the night. In the 1970s, Yoshiyuki used infrared film and filtered flashbulbs to capture images of secret sexual encounters in Tokyo’s public parks. The series, “Untitled” (1971), reflects the desire of Tokyo’s youth to escape from the stigma of premarital and homosexual sex. The public parks, under nightfall, provided a haven for young couples who had nowhere else to go. The images are shocking and real, as we become open spectators to a traditionally private activity.

Deutsch, whose “Night Sun” (2000) series is the most recent example of night photography, used a helicopter to capture Los Angeles’ vast suburban sprawl, shining a police light on roofed bungalows and faux-Spanish villas. The photographs are extremely deep and subtle; as you continue to look, small details begin to emerge—a parked car or abandoned bicycle, for example—that change your perception of the images, giving them a strange, almost foreboding quality.

It is important for exhibits like this to exist—technology has simplified our lives in a way Stieglitz may never have imagined and understanding the artistic values that went into these images can augment our appreciation. The night has always existed, but we’ve only been able to truly capture it within the last century.