The Psychological Toll of Racism

September 16, 2020

On May 25, the unjustified and brutal killing of George Floyd and countless other innocent civilians at the hands of police catapulted the Black Lives Matter movement into the national conversation. The topic of racism and its impacts, in particular, was elevated in this discourse.

Racism is a socio-historical category that is used to separate groups based on their physical attributes. It is perpetuated when individuals in the “in-group” hold and act on certain beliefs and attitudes towards people in the “out-group.” Racism can occur on individual and institutional levels, but it can also be internalized.

Shellae Versey, assistant professor of psychology, describes racism as “a set of structural privileges and advantages based on racial group designations, maintained through media, ideology, policies, norms and practices that preserve systems of inequity and racial dominance.”

As a “system of dominance,” racism gives the dominant group of society certain privileges and power over the non-dominant group. When these power dynamics are fleshed out in the public and private sphere, the out-group can experience immense psychological distress.

“The experience of racism, whether it occurs on an interpersonal, institutional or structural level, can definitely compromise our individual and collective mental, psychological and physical health and well-being in a variety of ways,” Jeffrey Ng, Psy.D., director of Counseling and Psychological Services (CPS), said. “Since the mind and body are inextricably linked, these mental and behavioral health concerns can negatively impact one’s physical health.”

Stress is just one symptom of racism that is widespread among people of color. This chronic condition can also be associated with other chronic diseases including heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, gastrointestinal diseases, depression and anxiety.

“The stress associated with racism has many different dimensions,” Elizabeth Raposa, assistant professor of psychology said. “Just to name a few examples, on a daily basis, racism can be experienced as micro-aggressions, or subtle (often unintentional) insults or discrimination. But structural racism is also woven into the fabric of our society in ways that create systematic, contextual stressors. Poverty, housing and job discrimination, police brutality, and a racially biased legal system are all ways that structural racism contributes to chronically stressful life circumstances for people of color.”

I have seen customers yell at my father for not knowing a lot of English and it has physically made me cry for days and my chest aches as all you want to do is protect the ones you love from moments like these. Nyckole Lopez, FCLC ’22

Trans-generational trauma can act as another implicit stressor caused by racism. Generational trauma can be transmitted through epigenetics and is described as the inheritance of beliefs, behaviors and patterns from older generations. Children are socialized from an early age to acknowledge they are different from others through stories told by their grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles and older siblings.

Raposa said, “racial trauma can also be transmitted across generations within a particular culture, with younger generations inheriting the stories and legacy of past oppressive experiences (such as slavery), creating another dimension of stress associated with racism.”

“My parents and family are from Ecuador and faced an immense amount of discrimination when they immigrated to the U.S.,” Nyckole Lopez, Fordham College at Lincoln Center ’22, said. “I have seen customers yell at my father for not knowing a lot of English and it has physically made me cry for days and my chest aches as all you want to do is protect the ones you love from moments like these.”

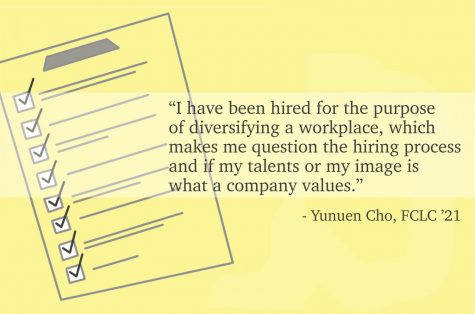

Additionally, structural racism impacts access to education, healthcare, criminal justice, employment, community and housing, all of which can affect one’s mental health.

Structural racism can “contribute to internalized racism, diminished self-esteem/worth, decreased authenticity, imposterism, hypervigilance and/or heightened nervous system arousal,” Ng said. “All of these experiences increase our vulnerability to various mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, social isolation, self-harm, suicidality, and various externalizing behaviors, such as substance abuse and aggression.”

Frequent exposure to the consequences of structural racism results in racial trauma.

“I have faced countless times where I feel immense anxiety throughout class because I realize I did not have the resources as other students who were accepted,” Lopez said. “When I have been called on and looked at weird because I don’t know the answer whether it be a word I never heard before or a book I never got to read in my high school because of lack of funding, I felt like an imposter in Fordham, I felt like I did not belong at all.”

There is an inequitable distribution of resources across racial lines which undeniably has affected the achievement gap among students of color.

“It is a difficult thing to sit down with yourself and push that you do deserve it because it may always feel like you don’t,” Lopez said. “But when it comes to the effects of internalized racism, it is extremely vital to keep yourself grounded in the reality that you worked hard and have faced a lot.”

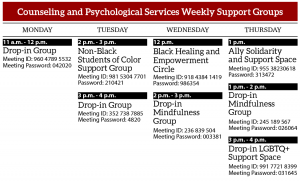

To address the impact of racial trauma on students, CPS has launched weekly support group meetings to discuss racial justice and to give students a platform to share their own experiences.

Racism itself is a social construct; however, because of its widespread implications on each institutional level, it can gravely affect the mental health of marginalized individuals. Professor of Sociology Clara E. Rodriguez, Ph.D., said that racism is “like other ’isms, which convey the idea that you are not as equal, worthy, or trustworthy. And, we all lose when not everyone can contribute to the best of their ability.”