Flesh and Blood: A Post-Post MLK Day Reflection

PHOTO COURTESY OF CALEB HAINES

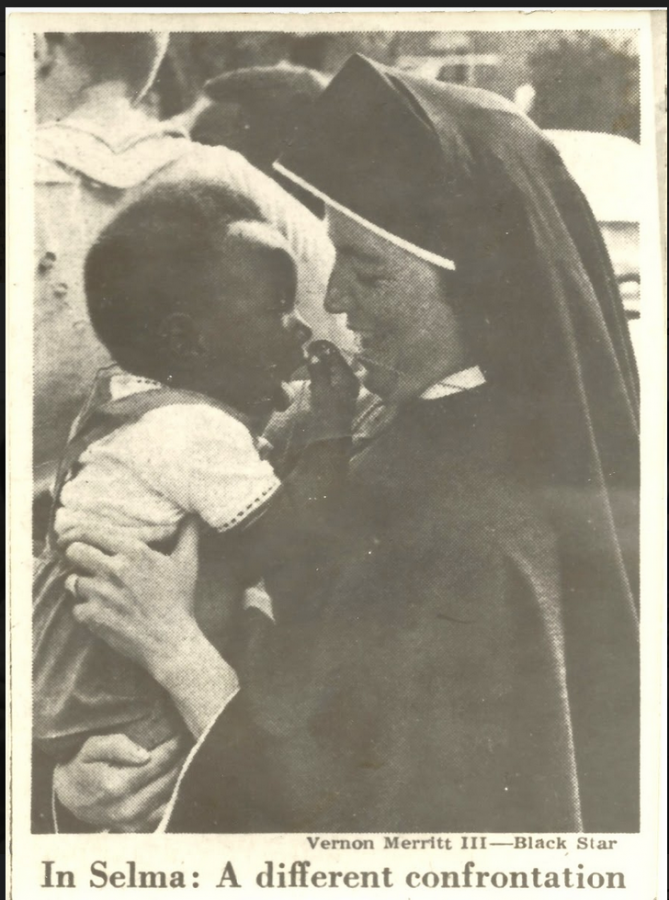

In a photo published in Newsweek on March 29, 1965, the Selma to Montgomery marches, the writer’s great aunt holds a young child.

January 28, 2020

My great aunt Kathleen was captivated by giraffes, played the meanest hand of cards you’ve ever seen and was a Catholic nun for over 25 years.

Every Monday growing up, I would go to her room in my grandmother’s house, where she would give me the sweets my parents shied away from and teach me different card games — including War, which she taught to me as “Peace.”

Great Aunt Kathleen also marched at Selma with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1965. Although she graduated with a Masters in Social Work from Loyola Chicago, she became the first nun appointed to a city commission in San Francisco’s history and represented Caritas, an international Catholic charities consortium, at the United Nations.

It’s strange to be directly confronted with evidence that someone you’re connected to participated in events of national magnitude. It’s like having something you read in your textbook brought directly to your doorstep. Existing with the knowledge of my great aunt’s life violates a fundamental paradigm that I, like everyone else, carry with me: There are heroes and there are villains — and then there’s the rest of us.

How can I, someone who once stepped on a rake out of a desire to emulate my role models Tom and Jerry, be related to someone who worked to make the world a better, less horrible place? And who am I to even talk about it? It’s easy enough to crank out 500 words, but it feels incredibly presumptuous to try to write an article about social justice.

It’s the ultimate arrogance, attempting to impose a vision on the world with zero qualifications to do so. In a zombie flick, I’m the one who dies in the first minute of the outbreak at the grocery store while fighting for the last can of Grape Crush, not the one who finds the cure.

But I will step out of the shadows of moralistic ignominy, if only briefly, because I think it’s important to discuss legacies like my great aunt’s, as they raise important questions about whether or not heroes exist — and if they even should.

The hero narrative is an important part of the human search for meaning, but it can also be used to exculpate, as it provides exoneration from the responsibility of moral accountability.

In a movie, everyday citizens can rest easy while superheroes rush around, saving the day without a sweat. Superman will always save Lois Lane, so why bother worrying about it? But in the real world, assuming that someone else — someone else who is smarter, bolder, and more heroic than you will step in — can have devastating consequences through the bystander effect.

Even though their deification is deserved, idolizing people like my great aunt — something I myself am very guilty of — allows us to get away with an unsettling conclusion: If we’re just human, and people like my great aunt and MLK Jr. are other-worldly in their noblesse, then we are not capable of participating in social justice, and moreover, should not do so.

One of my favorite writers, Jason Pargin of Cracked.com, phrased it this way: “there are two ways to dehumanize someone: by dismissing them, and by idolizing them.”

It lets us escape responsibility for making the world a better, kinder and more inclusive place. I certainly have no degree in discussing social justice (or any sort of degree yet), but you don’t need all of the answers to agree that placing the onus for creating a world that we are not completely ashamed of is one that should not and ultimately cannot be shunted to a single person, or persons.

I am not my great aunt. I remain fairly neutral toward giraffes, and I only play a decent hand of cards. But I have inherited her legacy, by virtue of being made of the same flesh and blood of which she was.

What I do with it?

That’s a great question, one that I’ll never be able to answer through self-deprecation in the name of hero worship.

It’ll just be a question I have to answer as I begin, imperfectly, just like we all must.

Dric • Jan 29, 2020 at 12:05 am

Nice, Grace