‘Frontier Gandhi’ Aims to Expand the Frontiers of Western Thought

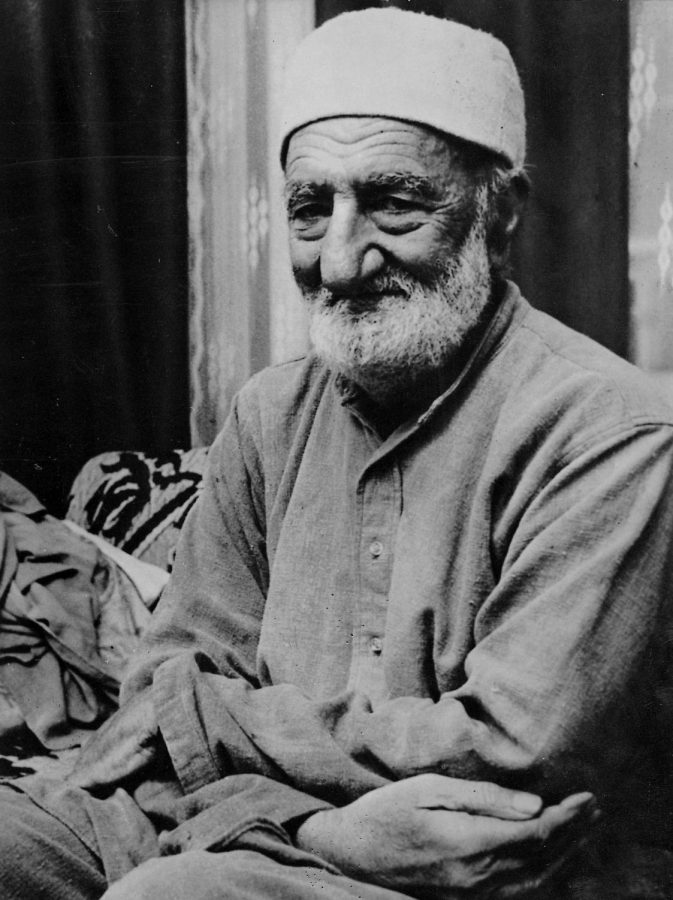

COURTESY OF KHALID KHAN MOMAND VIA FLICKR

Badshah Khan, a Pashtun independence activist, created an army of 100,000 Afghani and Indian nonviolent protesters, the Khudai Khidmatgars.

November 13, 2019

Thierry McLuhan’s 21-year-long project started with a book gifted to her by one of the literature professors at University of California, Berkeley. Called “Nonviolent Soldier of Islam,” it was the first biography of Pashtun independence activist Badshah Khan (1890-1988) to be published in the English language. It had lain on her bedside table for two months until one night, she decided to open it. “From the first moments of reading it, I realized that I had encountered a giant of human spirit, a man, who always knew how to be tall in every way,” McLuhan said.

Inspired by Badshah Khan’s story, McLuhan decided to retell his life’s achievements through film. In his years as an activism leader, he created an army of 100,000 nonviolent protesters, the Khudai Khidmatgars, from the multi-ethnic communities of Afghanistan and India. They were men, women, children; Hindus, Christians, Parsees, Sikhs and Buddhists who came together to advocate for peace, justice and human dignity.

His success is often likened to a fairytale since he managed to make warriors of peace out of a nation famous for having “violence in its blood,” as one of the narrators in the documentary put it. A friend of Mahatma Gandhi, he put Islam in conversation with Hinduism, and he promoted his religion’s inherent compatibility with nonviolence. Yet, he rests largely unrecognized in modern India since there is a fear of unseating a Hindu from the pedestal of nonviolence, rather than letting a Muslim and a Hindu share a seat.

Badshah Khan is similarly unknown in the West, even though he had been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize twice. Outraged and perturbed by the erasure of Khan’s history, McLuhan felt compelled to create a project, a documentary, that would tell the story of Khan’s heroic life as a peace activist and inspire a wider recognition for his achievements, as well as “advance a greater, broader and inspired understanding of what is currently perceived as Muslim, Pashtun and Afghan.”

The road to making the documentary was not easy. No one in the U.S. wanted to fund such a project, and, even with funding, American film crews were too afraid to go into the Khyber Path region. Finding information presented an equally difficult issue. McLuhan often worked under impossible circumstances, which included spending a sleepless night in the Kabul archives, reading under candlelight. She and her non-American crew were arrested on a number of occasions, and the constant sandstorms often put her video equipment in danger.

McLuhan proudly called her project “the most determining experience in her life,” having successfully produced a one-of-a-kind documentary against all odds and learned two new languages in the process.

The delight which McLuhan experienced during her interactions with the surviving Khudai Khidmatgars was worth the struggles she went through in order to make the documentary. “The women were the greatest kind,” she said. “It didn’t take me much to get them talking, and once they started, they couldn’t stop.” The women’s empowerment to speak about their experiences was yet another achievement of Khan, since a key part of his career as an activist was dedicated to promoting women’s rights. When Khudai Khidmatgars were active, women completed the same tasks as men, and even more.

At the time of the documentary’s creation, most of the Khudai Khidmatgars were past the age of 100 and lived in secluded settlements. Few of them are still living today, while the majority of the Western public is unaware of Khan’s legacy. “The Frontier Gandhi” received critical acclaim at independent film festivals such as the Third Middle East International Film Festival (2013), where it won its first award. Yet it remains inaccessible to the general public, as mainstream media are reluctant to pick it up. “I sent it to one distributor, and all they told me was, ‘Nice music,’” said McLuhan in disbelief.

McLuhan’s situation is a reminder of how difficult it is to produce and distribute an unconventional film that tells a non-Westernised story. Her presentation invited a question: Does a film that took 21 years to make require another 21 years to get distributed?

“You don’t want to make a book for the future, you want to make a book for people to read,” mused McLuhan. “There is a lot of political and religious fear towards Islam in this country, so people with big money will not endorse”a documentary about a Muslim activist.

Yet, McLuhan persists. Her next steps are to pitch Frontier Gandhi to online streaming services, such as Netflix, which are known for supporting non-traditional media projects. Smaller, private events have already proven the film’s social power. For example, select police departments have been showing it as part of their rookie program to promote tolerance. “I want to take forth the seed that he [Khan] planted, and water it,” shared McLuhan, determined not to let Khan’s legacy disappear in the annals of history.