Minimum Tolerance Does Not Count as Love

September 17, 2019

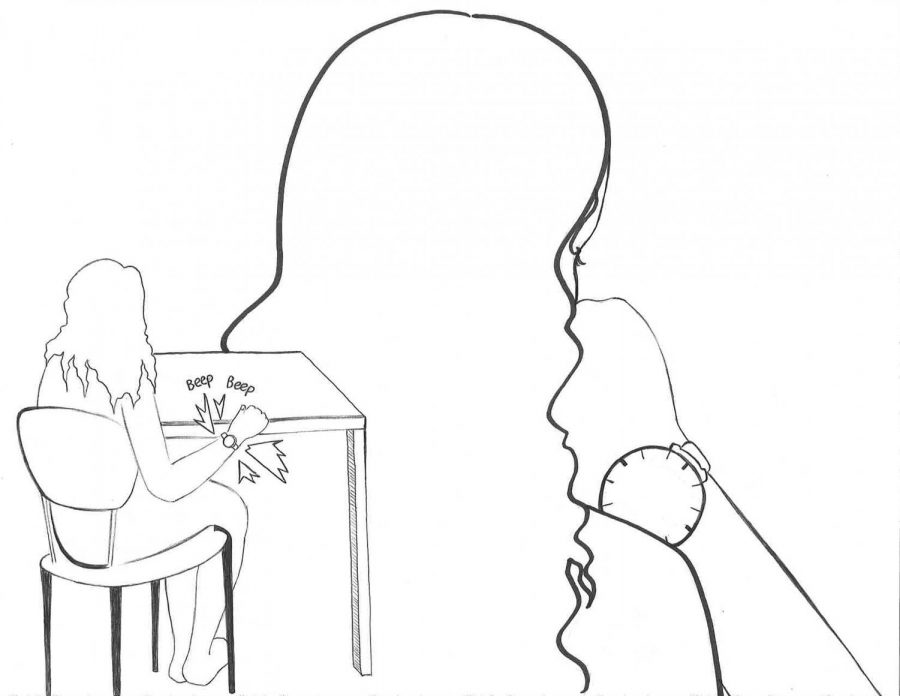

When I was in the eighth grade, I had one of those cheap Walmart watches that glowed in the dark. The kind of watch for which you immediately lose the owner’s manual.

My watch always screamed at noon. I didn’t know how to shut it up. Normally this would be the death of a shy kid, but I didn’t mind. My friend James would always smile and point and say, “Again? Yo, why you keep letting this happen?” and our friend G would always mumble, “I don’t know why you haven’t smacked him.”

Because he’s my friend. Because he’s funny. Because, who cares?

I did not care until the day it went off as usual, and James said, “Hey, terrorist. Why haven’t you learned how to chill yet?” I smiled once, twice, confused. Laughed, “I’m sorry” — button-clicked the noise away.

In my head, every time the alarm went off, my watch screamed. In James’ head, my watch mimicked the funny beeping of a Muslim’s bomb. It took far too long, 11 months, for my confusion to turn into anger, anger borne of a realization short and strong: I did not deserve his condescension.

I grew up in Walton County, 40 miles east of Atlanta, my home caught between three highways and still in the middle of nowhere.

The sickening thing about small Georgia towns, like any small town, is that there is a comfortable and unjust order. In my town, white people don’t belong strictly up top; they belong anywhere. In wealth or in dirt, their existence is uncontested in all instances. Black people belong strictly below, preferably separate, the acceptance of their existence contingent upon the most infuriating of terms — “knowing their place.”

And then there are the Muslims. In my outlying metro county, the Muslim community is spare. Established is one small, clean, peaceful masjid in a renovated Dollar General. In this space, we are sacred, but in all others, Muslims that look the color of sand — sand n—–s — terrorists — have no place to visibly exist without fear or apology sitting ready in their throat.

My school’s Muslim population was my sisters and I along with a smattering of Iranians and Indians. A few black Muslims, too, but I know this only statistically — I knew none individually. Whereas black Muslims in America have to literally wear their religion on their sleeves to be assumed Muslims, anyone who looks vaguely Arab, regardless of their beliefs, wears “Muslim” on their skin.

My best girl friends were white and my best boy friends were black. In the eleventh grade, we Googled all the Sofia Anjums, and a Pakistani poet’s work in swirly Urdu script floated to the top of the results. One of my best white girl friends said, “Hey, Sofia can just read it” — I could not — and, “Oh well, it probably just says, ‘Kill all Americans’” — it did not. This time my anger was immediate and my words were precise as I schooled her in the facts of strife. Her remorse was real, her incendiary foolishness cleared. I forgave her, but I hold the memory close to my chest.

I was kid becoming woman, my holey jeans becoming skirts that by graduation hit above my knees. I argued for Syria and I argued for Palestine and I argued against the rhetoric that my Ummah, my Muslim community, was a cruel and festering race.

Before, I was an excuse not to lesson plan the one-day unit on Islam. I was an innocent. But as I became belligerent, the teachers began to treat me differently. In Current Issues, I was left high and dry by the self-proclaimed self-made assistant teacher in every single debate that edged near Islam. He would validate comments, careless, baseless, with no concern for the harm and hate that they accredited. In World History, when we talked about the Renaissance and learned about humanism as faith in human excellence, one boy said, “So, the exact opposite of Islam, right?” The young, liberal teacher saw my face lose light but made no effort to correct the student.

But the teacher did laugh. That laugh. That weak laugh of someone who thinks something is wrong but does not want the trouble of action. My weak laugh from eighth grade. The weak laugh that doesn’t mean that I am hated, but that I am not worth being advocated for.

I molded to those who loved me anyway: my Republican best friend hard-won from a screaming match in U.S. History, my Communist friends who loved me as an error in the system. I loved them for loving me in spite of my otherness.

And they did no wrong in accepting me, but I committed a double-edged structural sin in elevating them for doing the bare minimum.

First, I was actively condescending. I assumed that the base level of compassion and empathy of which these individuals are capable was lower than my own. I assumed that they lacked the capacity to ever understand human beings outside of their small, clearly cleaved world, consequently giving them freedom from the full weight of their choices and their full responsibility to educate themselves.

Second, I passively enabled condescension. I accepted less respect for my Ummah than I would accept for any other group of humans.

I should not feel content when I am shown minimum tolerance, and I should not feel joy when I am shown minimum acceptance. I should not have to use the language of “anyway” and “in spite of” when I speak of love. I choose instead to hold all people accountable to the highest standard of love.