Balenciaga, Ballet and a Biennial

A New York exhibit roundup

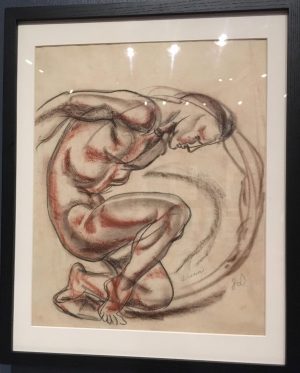

ROXANNE CUBERO/THE OBSERVER

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney and the New York Public Library all have special exhibits that aren’t to be missed.

August 25, 2019

New York is a culture capital for a reason. Well, multiple reasons, and many of them are museums. Whether you’re looking to impress your art history professor with a little extra knowledge or need a quiet hiatus from the city outside, a museum can provide. A walk across the park or across the street can bring you face-to-face with history, fashion, fine art and more. You have the whole semester to learn about it all from a textbook, but only a few weeks to see some of these exhibits displayed live. And if you find yourself becoming a museum buff afterward, there are plenty more — many with free or student-discounted admission — where these came from.

CAMP: NOTES ON FASHION

By ROXANNE CUBERO

Asst. Features Editor

Until Sept. 8, swarms of lay-clothed New Yorkers and tourists alike congregate at The Metropolitan Museum of Art to answer one question: what is camp?

The answer is found in Gallery 999. When you enter the exhibit, it looks like your typical art gallery, save for the hot pink walls. You are first greeted by a statue of Antinous, the lover of Roman Emperor Hadrian, striking a contrapposto pose, the “archetypal camp pose” according to Head Curator of the Costume Institute Andrew Bolton.

The exact definition of the “camp” theme that ties the exhibit’s fashion together is meant to be elusive.

This first section of the exhibit serves to explore the etymological history of camp, whether it be used as a verb in Molière’s 1671 play, “The Adventures of Scapin,” an adjectival euphemism for homosexuality in the 19th century or Oscar Wilde’s exemplification of the noun “camp.” This is all before Christopher Isherwood would distinguish “high” and “low” camp, and before Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp,’” which Bolton used as the framework for the exhibit.

The final section is like a Piet Mondrian painting, if he used neon colors. The oversized shadow boxes along the walls display camp fashion from iconic camp designers like Rei Kawakubo and Jean Paul Gaultier, as well as works from new talent like Molly Goddard and Tomo Koizumi. In the center is a display solely dedicated to accessories, featuring platform Balenciaga Crocs and a flamingo mask by Schiaparelli, among other extravagant items.

Ultimately, if you haven’t figured out what camp is, you probably never will. Or you just haven’t visited the exhibit yet. “Camp: Notes on Fashion” serves to give laypeople — you and me — the tools to understand camp, but still, not everyone will get it. And that’s okay. As scholar Fabio Cleto states, “camp is a question mark that won’t let its line be straightened up into an exclamation mark.” Bolton doesn’t want people leaving Gallery 999 knowing what camp is; he wants them to still think, what is camp? The power of camp is in its lingering presence in the human consciousness and in the human efforts to try to define it.

ARCHIVE IN MOTION: 75 YEARS OF THE JEROME ROBBINS DANCE DIVISION

By GILLIAN RUSSO

Arts & Culture Editor

If you’ve heard of Genevieve Oswald, kudos — I regret that I didn’t learn of her before she passed. To anyone interested in the arts, history, philanthropy, design or even international relations, she might become your new hero.

Seventy-five years ago, Oswald was fresh out of college when her reference-librarian job at the New York Public Library (NYPL) led her to create a division solely for the preservation of historical dance materials, a task previously encompassed by the music division. The NYPL for the Performing Arts’s exhibition, “Archive in Motion,” primarily traces her career as the Dance Division’s curator, researcher and leader for 43 of those years, and highlights the continued progress made in the following 32 years.

Artistic renderings, films and other archival materials aim to preserve the ephemeral nature of dance.

You may find yourself between Isadora Duncan’s regal purple sheath dress and sheet music with Jerome Robbins’ original choreographic notes in the margins. Step (ball-change) a few feet away and you can watch Agnes de Mille perform at the charity gala that saved the building you’re standing in, surrounded by almost-living paintings of dancers in your periphery. Then shuffle along toward a richly woven Japanese kimono gifted to American researchers by an emperor on your left, and excerpts from antique books on your right.

The exhibit is a treasure trove for dance buffs, but what gives it universal appeal is that it taps into larger historical themes. The library acknowledges that even the beautiful history of dance was not immune to the ugliness of racism, sexism or exclusion. Before the division was founded, co-founder of the New York City Ballet, Lincoln Kirstein, dismissed the young Oswald for attempting to launch the project. A plaque beneath the small section of materials on black dancers acknowledges its smallness and the years of discrimination against black artists that caused it.

The overall message, though, is a positive one: art ultimately brings people together. Kirstein was eventually moved by Oswald’s determination and would become one of the division’s greatest benefactors. The preservation of black artists’ work has grown since the Dance Division began to film performances. Until January, global history is on display, underscored by gentle orchestral music and the rhythmic hum of an electric circuit that just might put a little lilt in your step as you walk through.

Coming Soon: On Sept. 18, the NYPL for the Performing Arts will open an exhibit on Hal Prince, the late theatre producer whose credits, like “West Side Story” and “Cabaret,” shaped Broadway as it’s now known.

THE WHITNEY BIENNIAL

By GRACE TYSON

Contributing Writer

Whether art imitates life or life imitates art, the eclectic, highly provocative spread surveying North America’s most relevant and affective new artwork at this year’s Whitney Biennial proves that this current American life is more volatile than ever.

The highly anticipated biennial contemporary art exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art has a history of amplifying the country’s strongest up-and-coming artistic voices. This year, between the turbulent political climate and the museum’s biggest controversy yet, expectations for the collection are exceptionally high, if not a bit uncertain.

This is the first biennial to be curated entirely during the Trump presidency, and all the art reflects the changes and traumas his administration has brought to the art world and the country at large. Recent condemnation of the Whitney’s Board of Trustees by museum employees, artists and critics has only added to anxious discourse surrounding the Biennial. Following the discovery that former vice chair Warren B. Kanders’ company Safariland manufactured tear gas used against 2018 migrant caravans, several artists withdrew their pieces from the program. Kanders left the Whitney on July 25, stating in his resignation letter that he “does not wish to play a role … in [the museum’s] demise.”

The Whitney Biennial examines the relationship between the political and art worlds, and the social issues they both handle.

Curators Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley certainly did not disappoint, however, in providing a comprehensive representation of how art has reacted to or shaped the chaos of our time. The collages of El Paso, Texas,’ Troy Michie investigate the relationship between media representation of marginalized communities and the political reality of those communities. The photography of John Edmonds showcases intimate portraits of black identity that challenge objectification of the black body. Sofía Gallisá Muriente’s short film examines colonialism and relations between her home, Puerto Rico, and the United States, while deaf artist Christine Sun Kim’s charcoal drawings express her frustrations with the treatment and perceptions of disabled communities. The sound art of composer Laura Ortman explores post-genre music by fusing classical violin with indigenous musical traditions, and Argentine Agustina Woodgate portrays the erosion of existing power structures and labor systems through her installation of synched analog clocks. Altogether, every piece in the Biennial has something poignant to convey about what life in our country has been, what it is becoming and what it ought to be. This year’s biennial is not to be missed, so be sure to take a look before it closes on Sunday, Sept. 22.