Religion Enters Presidential Race

Romney Faces Scrutiny as a Result of His Mormon Faith

May 26, 2011

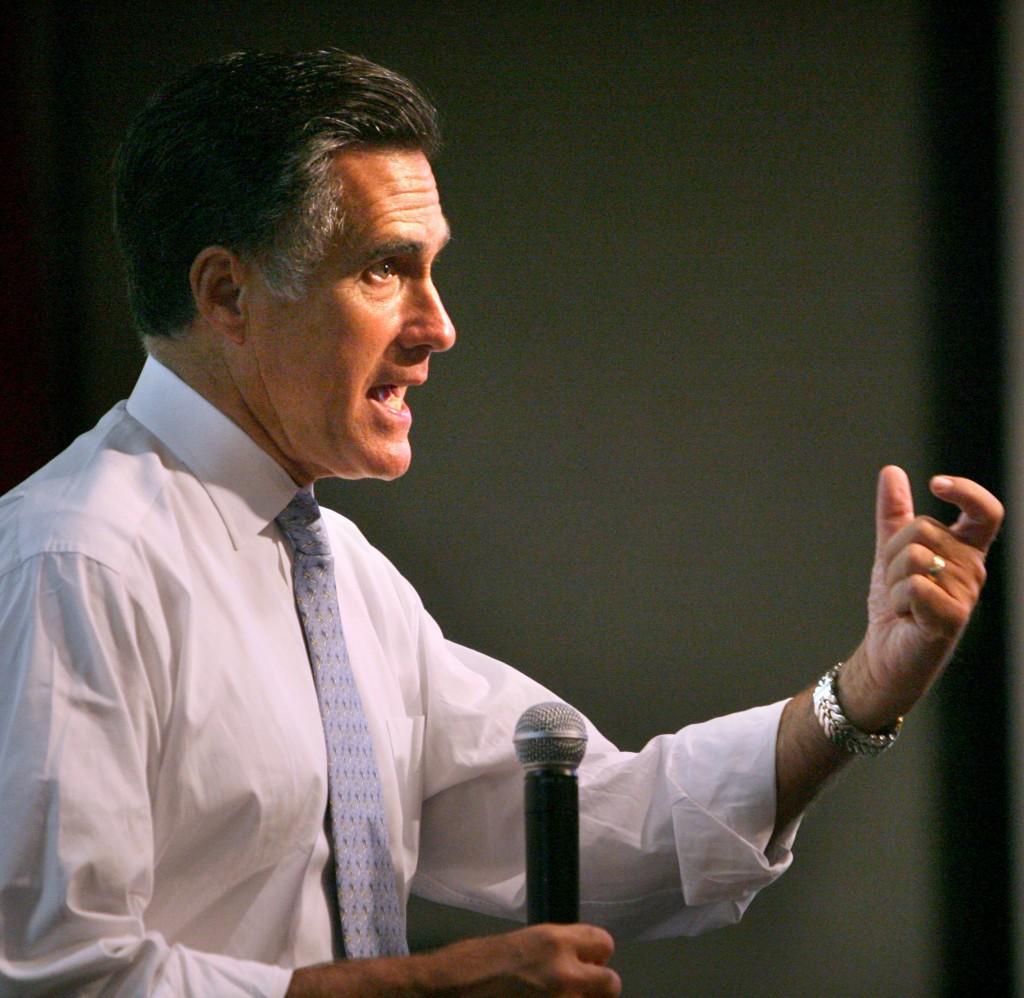

FCLC—Whether a leader claims God as an ally, Allah as an adviser or Jesus as a homeboy, theological entities are no stranger to the political arena. America does not prevent anyone from running for political office on the basis of religion, but that does not mean religion never enters the equation. As a new crop of candidates vies for the nominations of their respective parties for the 2008 presidential election, religion is a factor again. Republican candidate Mitt Romney, former governor of Massachusetts, in particular, has faced constant scrutiny as a result of his Mormon faith.

America will soon enter its eighth year under the leadership of a president who openly allows his Christian faith to influence his political decisions. Romney faces a challenge because voters have historically been wary of candidates from minority religions, as was the case when John F. Kennedy, a Roman Catholic, ran for President in 1960.

Romney was born in Michigan to a Mormon family and attended Brigham Young University, a Mormon university. Just as with Kennedy, some voters have expressed concern that Romney will allow Church doctrine to dictate his actions, a fear echoed in a recent Time Magazine article. The author, Michael Kinsley, commented that: “If Romney’s church doctrines require efforts to impose these restrictions on others…he cannot be a good Mormon and a good President.”

An official statement on the Web site of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints serves as a response to such suggestions: “Elected officials who are Latter-day Saints make their own decisions…while the Church may communicate its views to them…it recognizes that these officials still must make their own choices. The Church’s mission is to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ, not to elect politicians.”

Dr. Peter Steinfels, co-director of the Fordham Center on Religion and Culture at Lincoln Center, says he sees “no basis for the claim that, to be a good Mormon, a Mormon president would have to impose his doctrines on the nation. It sounds a lot like the old anti-Catholic canard that a Catholic president, to be a good Catholic, would have to subject the U.S. to the rule of the Pope.”

Many people believe that separating religion from political practices can be a challenge. “Religion is a means through which to order the universe in some way; thus, it must play some role [in politics],” Joel Rowe, FCLC ’09, said. “[Candidates’] decisions can be separated [from their beliefs], but not their decision making process.”

“I don’t think it’s fair to ask a candidate to divorce him or herself between their job and their faith,” Meaghan Doherty, FCLC ’09, said. “However, I don’t think it’s fair for a candidate to assert his faith throughout his or her job or use his or her powerful platform to endorse a religious agenda. It’s called balance.”

That desire for balance is echoed by several other Fordham students. “I don’t care what religion a candidate is as long as it isn’t mentioned in every speech or used to justify major political decisions,” Lauren Davis, FCLC ’09, said .

Jordan McHenry, FCLC ’09, believes that “morality should play the largest role [in selecting a candidate]. The problem is that too many people associate the two.”

Although Steinfels “see[s] no connection between religion and political skill,” he does not believe religion is irrelevant in the political arena. “For many people, religious beliefs and practice have a lot to do with their character, how it was formed, how it is maintained. I don’t think religion is something to be automatically set aside when voters are looking for clues about a candidate’s character.”

“Religion will always manifest itself in presidential nominations and elections because of its prominent role in history,” Doherty said. “I think that for the U.S., religion and politics will always share a bed.”