Bibles Are Books Too: In Defense of Religious Studies

July 8, 2011

Published: April 1, 2010

As college students, there are plenty of courses of study that we can select to make our parents laugh, cry or wonder why they’re shelling out so much money for tuition. Not necessarily because they disagree that the things we’re learning at school are important—though sometimes they do—but because there is an assumption that universities are for strictly liberal academic studies, and there is a very strict preconceived notion of what is academic and what is not.

What am I talking about? Among other things, theology and religious studies. There seems to be this widespread notion that the only people who study theology are regular churchgoers who take the Bible at its word, literally. Along with that (incorrect) notion comes the idea that religious studies can’t be used for anything other than the pulpit. Why? Because the Bible is fake, hasn’t influenced anything in the secular world and the only people who care about it are crazy fundamentalists. Except that isn’t true.

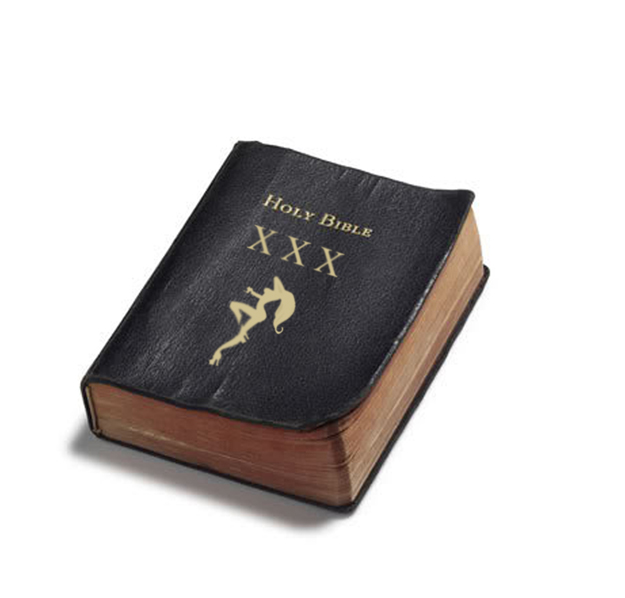

Recently, there was buzz about a campaign at the University of Texas San Antonio called “Smut For Smut,” which encouraged students and faculty to trade in their holy books for issues of Penthouse and Playboy. This took the idea that the Bible is merely fiction to a new level, equating it to pornography. Say what you will about the Bible’s historical accuracy or religious significance, but it is still a crucial text—sacred, literary or otherwise—that has dictated the way people all over the world in countless cultures and religious traditions have lived their lives for centuries. If that isn’t an important thing to study, I’m not sure what is.

Studying sacred texts, religion and cultural traditions is no different than studying history. In fact, the early history of many nations begins with religion. Weren’t the Colonies settled by those Brits who sought a place of religious tolerance outside the clutches of the Church of England? Think Pennsylvania and the Quakers, many of whom remained settled in my hometown in Bucks County. And if you’ve ever picked up a history book of the modern Middle East, you’ll see that it begins with the Prophet Muhammad, and that so much of the turmoil the region has faced over centuries stems from religious conflicts, whether over fundamental differences between Muslims, Jews and Christians or denominational differences between Sunni and Shi’a Muslims or Catholics and Orthodox Christians.

The United States is often referred to as a “Judeo-Christian society” and many of our laws and cultural traditions are based upon religion. Regardless of whether or not you agree with the separation of Church and State, there’s no denying that the Church influences society. After all, “One Nation Under God” is in our pledge of allegiance to the country. Legal tender is emblazoned with “In God We Trust.” President Obama recently hosted a seder at the White House in honor of the Jewish festival of Passover. Christmas Day, recognized as the birth of Jesus, is one of only 11 U.S. Federal Holidays, and has been since 1870. These are only the most obvious of religious influences on a seemingly secular culture. There’s also the fact that we have weekends—an idea that arguably grew out of the religious observance of the Sabbath. And you can’t forget about any upcoming holiday if you’ve been in any retail store ever, because Santa Clauses start appearing in October, followed by red hearts in celebration of Saint Valentine, the patron saint of love who was also an early Christian martyr. Then come the chocolate bunnies and jelly beans for Easter, which is actually the holiest season of the year for Christians. Even seemingly secular holidays have religious roots: don’t forget that Halloween is actually All Hallows Eve, the eve of All Saints Day, which is a holy day of obligation that requires Catholics to attend mass.

To be sure, the fact that now secular and cultural aspects of society were once religiously motivated doesn’t mean that every painted Easter egg comes with a divinely transcendent experience. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t still a reason why we do what we do. Just because the reasons may have been largely forgotten over centuries of progression and adaptation doesn’t mean they aren’t important. And those who study scripture, religious history, traditions and culture aren’t always focused on perpetuating faiths into the future—many of us are much more interested in exploring how religion has shaped our past, how faith has developed our consciousness and what that means for societies that continue to grow.

Bible scholars are still scholars. Religious history is still academic. It’s possible to be a doctor with a degree in theology—unless you completely underscore the entire notion of medical ethics, that is. Studying religious texts cannot possibly be equated to flipping through Playboy, and a degree in theology or religious studies is far from a waste of time—rather, it can be the jumping-off point for countless careers, including many in journalism, medicine, sociology and politics, among others. When something shapes so much of our history, government, culture and relationships, only ignorance can justify not paying attention. It’s about time people stop equating biblical and other religious studies with fundamentalist televangelists and understand that we are all, in some way, People of the Book. Perhaps with that understanding will come a better notion of how the world works and the paths we must take toward shaping a better society.