Sounds About White: The Lack of Diversity in Fordham Syllabi

Fordham syllabi have a problem with racial and gender representation

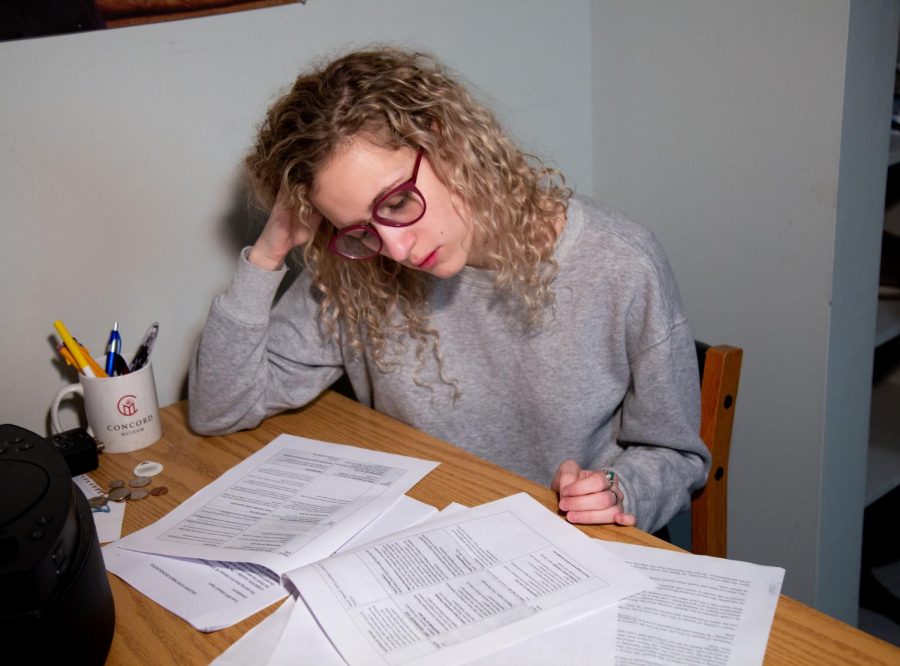

MARGARET GALLAGHER/THE OBSERVER

I was so caught up in the whirlwind of senior year that it wasn’t until classes began and I was a few weeks deep in work that I realized one glaring fact about the authors I was reading for my classes: they were almost all white men.

Fall 2018 was my final semester at Fordham University, and I had my eye on graduation. At the beginning of the semester, this meant color-coding my schedule, organizing my binder and renting all my required books from the bookstore for my six classes. I was so caught up in the whirlwind of senior year that it wasn’t until classes began and I was a few weeks deep in work that I realized one glaring fact about the authors I was reading for my classes: they were almost all white men.

Of the 35 authors that sat on my windowsill for the classes I took last semester, 29 were men and 32 were white. A shocking — or, depending on your expectations of Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC), not-so-shocking — 75 percent of these authors were white men. For classes on expansive topics such as literature of war, journalism and the digital age of creative writing, the representation on the required text lists was surprisingly narrow.

Anne Fernald, English professor and special advisor to the provost for faculty development, said that “the texts we read in common in class are at the heart of higher education: we gather together in classrooms to share our analysis and interpretation of what we have each read separately.”

These readings, undoubtedly important, carry the responsibility to be representative of the Fordham community and the world at large.

“A diverse reading list — in every sense of that term — is essential to a strong syllabus,” Fernald said. “Every professor will find their way to that diversity.”

However, it appears that not every professor has. Motivated by my findings in my own course load, I conducted a survey of 11 syllabi for FCLC courses in the fall of 2018, in which I analyzed the races and genders of required texts’ authors in each class.

Among the 11 syllabi, taught by 11 different professors, there are 83 total authors of required books. Similar to my personal survey of my own classes, 75 percent of these 83 authors are white men. Eighty percent are male and 87 percent are white. The least represented voice is that of women of color, six of which dot the various syllabi — a mere 7 percent.

These statistics stand in stark contrast to FCLC’s own demographics. According to Fordham’s Spring 2018 Demographic Profiles Fact Book, women make up 70 percent of FCLC’s student body, despite only making up 25 percent of reading lists’ authors. (Fordham’s reported demographics conflate the gender assigned at birth and sexual organs with an individual’s gender, and does not account for transgender and gender non-conforming students.)

As for race and ethnicity, Fordham reported that 59 percent of the FCLC population in Spring 2018 was white, 39 percent were students of color and 2 percent were “Race and Ethnicity Unknown.”

Theology Professor and Assessment Coordinator for the Theology Department Aristotle Papanikolaou is currently teaching Faith and Critical Reason, an introductory theology course required for all students as a part of Fordham’s Core Curriculum. Papanikolaou’s Faith and Critical Reason syllabus is one of the 11 surveyed above, and features nine required texts. Of these nine texts, there are seven white male authors, one black male author and one white female author.

Papanikolaou said he is “painfully aware” that his syllabus is lacking diverse voices, and participated in a department-sponsored seminar on teaching diversity earlier last semester. “It’s been a good experience being in conversation with other colleagues, as well as graduate students, who are helping me, as we help each other, think through this issue,” he said.

While adjunct professor of English Marwa Helal’s syllabus for her nonfiction creative writing class, Writing the World, is not included in the above survey (due to the fact that her course requires no full texts), it has been lauded by students as one of the most diverse reading lists they’ve had while at Fordham University.

“The authors included on Marwa Helal’s reading list have introduced me to voices and experiences that I have not been exposed to before in my education,” Anne Marie Ward, Fordham College at Rose Hill ’19, said about the class.

Centering conversation around pieces by authors of various racial, ethnic and gender backgrounds, Helal chooses writers for her syllabus “who have made me the writer I am, and those writers were not white men.”

When asked if it’s important to consider factors such as ethnicity and gender when choosing what authors will be required reading in a class, she said, “Absolutely. It’s important that we see each other and we can’t see each other if all we’re reading is white men.”

“If I sound angry, it’s because I am,” Helal continued. “Look at the world that old canon has made. I am not interested in that world … I am interested in making a new world and that means new ideas, new writings.”

Academia and Western culture, in general, have had a long history of erasing the voices of non-male and non-white individuals. In more recent years, academics have attempted to correct this exclusion and erasure with inclusion and intersectionality. Often, this correction can be seen in syllabi, as professors insert more non-white and non-male voices to their readings, in what is called the “add-and-stir-approach.”

While simply adding non-white and non-male voices into a syllabus that is centered around readings by white men seems conducive to progress, Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Professor Diane Detournay argued otherwise.

“[The add and stir approach] keeps the dominant structure intact — whether that be a syllabus that is male-centered, white normative, citizen-centered, heteronormative, et cetera, and ‘adds’ on difference,” Detournay said.

“This means that ‘minority’ authors/texts, which I mark this way in terms of the logic of add and stir, will always occupy the margins,” Detournay continued. “This approach is also tokenizing — it takes the form of having a week on disability, race, gender or native/indigenous studies, rather than doing the hard work of centering these critiques and overhauling the curriculum.”

Through the “add-and-stir approach,” non-white and non-male individuals are marked as distinctively different, and professors fail to challenge the very systemic oppression that has marginalized these authors in the first place. While adding these authors may help in the numerical evaluation of diverse representation in the classroom, it does not ultimately question the systems that have not only decentered non-white and non-male authors, but non-white and non-male students as well.

For Detournay, “going beyond the notion of diversity as a measurable and quantifiable end requires engagement at many different levels,” such as evaluating ethnocentric language in Fordham’s Core Curriculum, encouraging multidisciplinary conversations between faculty and prioritizing accessibility in classrooms.

A part of the problem that narrows the scope of syllabi is that they are created primarily in a vacuum by each individual professor. Faculty are trusted to write a syllabus that will best convey the information of their class. While departments may offer guidelines, it is ultimately the responsibility of the professor to determine required readings. The only exception is syllabi of Core Curriculum, which must be approved by subcommittees.

Nonetheless, both core classes and electives suffer from a white heteropatriarchal infrastructure, with white, male voices dominating reading lists regardless of whether or not they are a part of core curriculum, signaling that the problem operates at both an individual and systemic level.

A simple step in decentering non-white and non-male voices in the classroom, however, is to eradicate the vacuum through conversation and collaboration.

Helal stressed that dialogue among colleagues is necessary in making progress on syllabi, but pointed out that white or male professors cannot rely on their non-white and non-male colleagues to educate them.

“I don’t suggest asking your colleagues of marginalized communities as this adds to their labor,” Helal said. “Department heads should be taking this load on, that’s what they’re rewarded for.”

Helal suggested that a step in the right direction would be to grant faculty access to each others’ syllabi through Google Drive, where the creation of a syllabus can be a collaboration inspired by accountability.

“In my new role as special advisor to the provost for faculty development,” Fernald said, “I’m working closely with Rafael Zapata, the chief diversity officer, to encourage faculty to reflect these matters and to change their syllabi. I would welcome input from students both about the scope of the problem and what recommendations you have for addressing it.”

While conversations and changes are underway from both Fordham administration and faculty, they should still keep all lines of communication open. It is the duty of these authority figures to support students from varying ethnic, gender, sexuality, religious, disability and socioeconomic backgrounds, and to represent the diversity of the world in the classroom.

Now at the end of my undergraduate career, it’s clear that my studies at Fordham have been dominated by the white, male voice. Regardless, I hope the administration, professors and students continue this conversation and think critically about the voices we center in both academia and our world.