Review: Martin Moran’s ‘The Tricky Part’ Returns to Prove the Power of Testimony

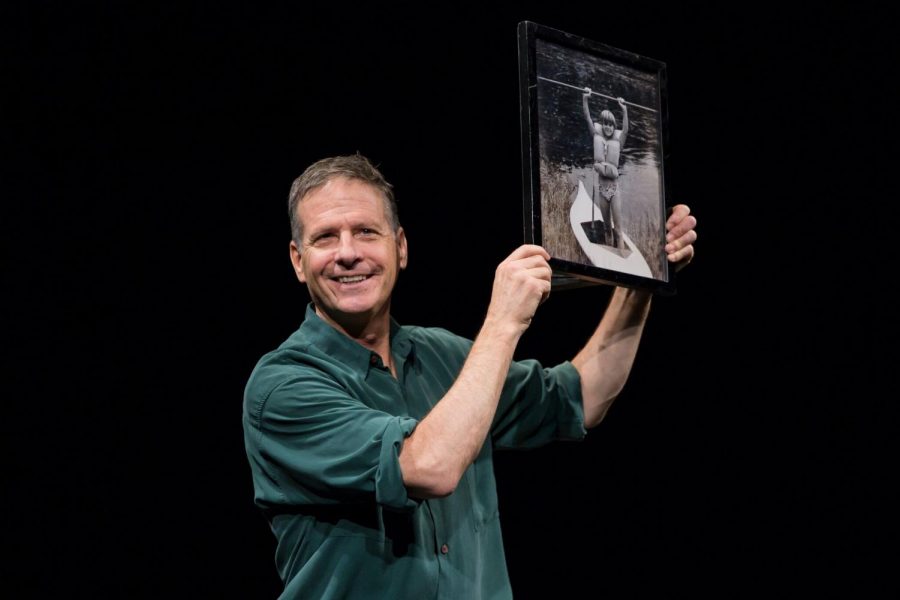

COURTESY OF EDWARD T. MORRIS

Martin Moran in his one-man show of trauma and testimony, “The Tricky Part,” returning again to New York, now at The Barrow Group.

Just as the meandering paths of story and autobiography can lull an audience into serene reflection with the therapeutic balm of testimony, the lights inside Martin Moran’s “The Tricky Part” lower, almost imperceptibly, into darkness. Slowly, as Moran sews his one-man memoir of incredible personal trauma, of a boy’s innocence perversely stolen and a man forged from a monster, the light leaves the room with such subtlety that its audience can’t help but wonder how they arrived in such terrifying twilight.

To save us from the depths of childhood lost, places where 30 year-old men pull innocent 12 year-old boys into their sleeping bags beneath the crystalline nighttime sky, is Moran’s still boyish face, now 15 years older than when his memoir of quiet terror in the 1970s first premiered off-Broadway.

Immediately your question should be one of age. It’s not hard to guess why the Barrow Group may have asked Moran to again surface “The Tricky Part,” its title imaginably referencing the delicate, toilsome process of reconstruction, of rebuilding identity after bottomless abuse and the perverse paradox of seeing the faces of our abusers as more than evil. But to come to “The Tricky Part” expecting our contemporary social sentience to jolt this play into some electric consciousness is naive.

Yes, telling the story of trauma in public memoir, erecting a monument to once-open wounds in hope that they may perform the work of permanence one person could never achieve, entails the larger organizational question of how ourselves and our social surroundings ought to be understood in relation to one another. That is autobiography. But solid and incontestable, careful and generous, Martin Moran, in testifying to having lived, armed only with story, disburdens his audience from focusing on the ambient noise, the buzz and clamor of the outside world, and with a trusting hand guides us to stare at the face of evil.

Of course, “The Tricky Part” does land with great weight as audiences come prepared to confront the visage of sexual assault, of suicide and self-harm in the wake of great sexual trauma. The autobiographical self is innately political, the interface of singular and shareable trauma, luminous and beating as it is in Moran’s beautiful narrative, a locus of active, breathing conversation between Moran and his audience. But in truth he is so disarming, such an incredible storyteller — more of a mathematician than a weaver, equipped with such precise recollection, slowly adding up the making and destruction of the child he once was, ticking off the points of trauma like counting constellations — that “The Tricky Part” is more than enough to stand on its own.

Haunting long after the show’s conclusion is the only physical artifact of Moran’s story present in “The Tricky Part,” a smiling photograph of his 12-year-old self, placed on a lone table next to a stool — the extent of this show’s constructed space. A small comfort, you think, to see proof of this man’s happiness in youth, even as he recounts the horror of that time. An image to take refuge in, you think, as Moran dives deep into the recesses of humanity. But all is shattered as “The Tricky Part” circles its conclusion and Moran reveals that the photograph was taken by his molester.

In an instant all becomes perverse, and you feel the pit of your stomach drop. No longer an image of innocence, but a sickening picture of pedophelia seen through the eyes of a human monster, that portrait of adolescence, permanent and never to be erased, burns a hole in the dark walls of “The Tricky Part’s” tiny theater, corrupting in no small way the light of childishness we all possess in the presence of great art.