Review: ‘Wild Goose Dreams’ Takes You to the Lonely Frontier of Digital Life

(COURTESY OF JOAN MARCUS)

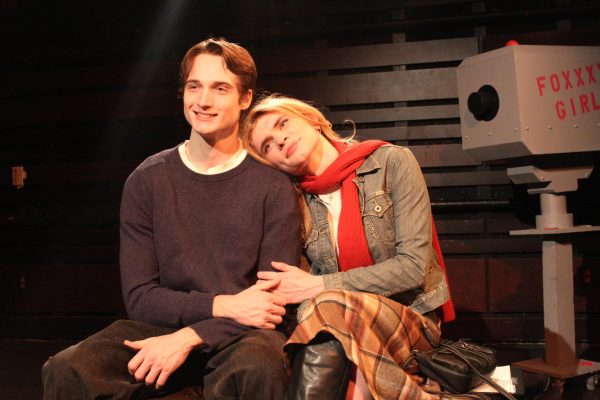

Michelle Krusiec and Peter Kim in the New York premiere of “Wild Goose Dreams,” written by Hansol Jung and directed by Leigh Silverman, running at The Public Theater.

You’ll need to fight through dense brambles of code and programming, sort through the clamor of social media’s infinite cacophony, to find the heart of The Public’s “Wild Goose Dreams.” Make it through undeterred by a piece of theater obliged to dilate social media’s relentless grip on our lives and you’ll find a story of profound loneliness and solitude, lost in a suffocating wood of ones and zeros.

With “Wild Goose Dreams,” a co-production with The Public Theater and La Jolla Playhouse, playwright Hansol Jung has attempted to stage a modern love story within the cold clutches of social media and internet technology, set to the dizzying, transitory techno-backdrop of South Korean modernity and political crisis.

In story, she’s crafted a beautiful, ill-fated romance. Guk Minsung is a goose father, a cloistered South Korean husband who sends every penny he earns to a wife and family relocated in America, who turns to the digital world of dating sites and social media for human connection, ever a hopeless endeavor. At sea in the world of online dating, Minsung meets Yoo Nanhee, a North Korean defector who’s worked tirelessly to erase her former identity. But the strands of digital connection can only go so far in establishing a real relationship between the two, just as they struggle to emotionally connect Minsung to his family.

In form, Jung has attempted something of innovation; as Minsung and Nanhee traverse their Facebook feeds and dating profiles, as they work to establish online personas and rectify their loneliness through digital connection, a Greek chorus of players, ever-present on the stage, narrate their digital lives. They sing code, chanting ones and zeros like monastic monks; when Minsung scrolls through his Facebook feed, they shout out in a babel of headlines and Facebook statuses the content appearing on his screen. New message! New email! Friend request! Poke! When Minsung and Nanhee type, they don’t speak; instead, proxies in this Greek digi-chorus relay their messages to the theater.

Michelle Krusiec, Peter Kim, and Joél Pérez (foreground), and company of “Wild Goose Dreams.”

Like Minsung and Nanhee, audiences spend the play traversing the boundaries between real and digital life, immersed in a social media void. Turning your phone off before the show won’t make a difference; “Wild Goose Dreams” will take you inside of it.

Its result only proves a hypothesis anyone could have made: that the digital universe is no place to set a play. This is an alien world, cold and disconnected, certainly inhospitable to human life. Chanting ones and zeros to recreate its atmosphere is not only an ineffective (and silly) creative endeavor; it’s a project whose end goal is numeric, detached from the breathing life of human experience.

While Peter Kim (“Yellow Face”) and Michelle Krusiec (“Chinglish”) make two valiant efforts to bring Minsung and Nanhee to life, they, like the digital disconnection written in their characters, struggle to meaningfully connect on the stage and to invest the audience at all in their romance. Though veteran director Leigh Silverman does well to stage Jung’s digital chaos, her fight to foreground the romance at this play’s core is invariably compelled to climb an uphill battle.

And, for the audience, that climb is an exhausting one. While Jung’s mission to stage a play between registers of physical and digital life lacks no imagination, standing in the way of social media’s endless barrage is not a place I want to be. Clint Ramos’ (Fordham Theater Department faculty) beautifully conceived set design, a bursting collage of neon and Korean typography that extends beyond the stage to wrap the entire Martinson Theater in brilliant color, does little to calm the senses.

Not to say that “Wild Goose Dreams’” meditation on family and fatherhood in Korea are not enriching, embracing human narratives. Just as Minsung struggles to maintain his sense of fatherhood, Nanhee strains to maintain her binding sense of family. In defecting from North Korea, Nanhee has lost her fatherland and her father, a void that grows deeper the longer she stays in the modern world of South Korea. Jung’s ultimate conclusion — that no father wants back the wings he gives his child — is a profoundly poetic (indeed, human) meditation needed to warm a play otherwise confined to the cold interior of digital life.